The Stone Roses: The Very Best of The Stone Roses

This album arrives with sleeve notes by John McCready that highlight a crucial truth: the story of The Stone Roses has been written and rewritten endlessly since the release of their self-titled debut. It’s a folklore defined by Jackson Pollock-inspired paint splatters, high-profile court dates, a legendary show at a disused chemical plant, and oversized flares. In the years since this specific collection surfaced, that story has even added two major reunions to its messy, brilliant timeline.

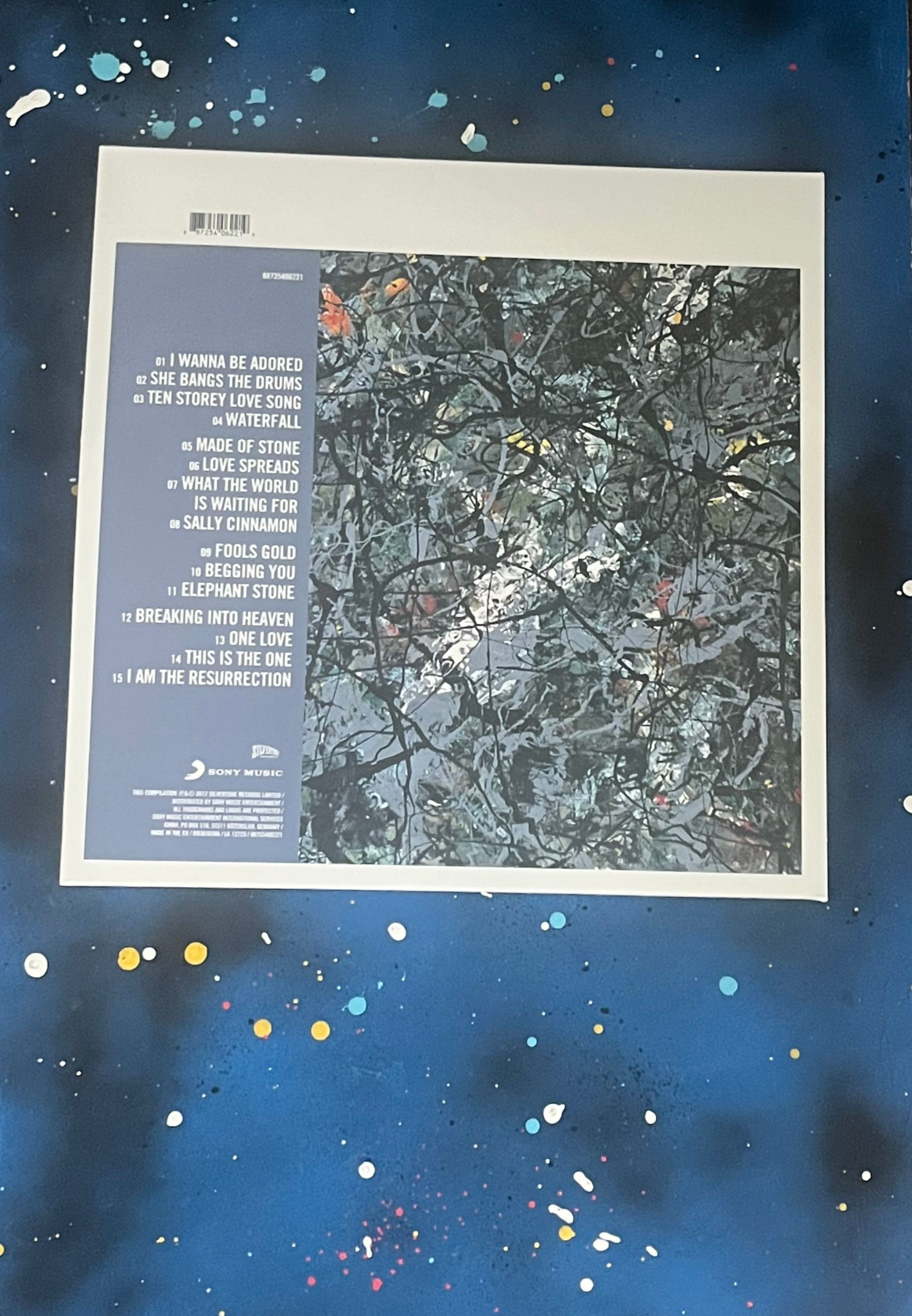

Originally hitting shelves in 2002, this was the first compilation officially signed off by the band. Previous attempts felt like placeholders; 1995’s 'The Complete Stone Roses' famously included a truncated three-minute edit of 'I Am the Resurrection', presumably for fans who found the original a bit "lengthy", while 2000’s 'The Remixes' offered the 'One Love (Utah Saints mix)', a dance floor hybrid the world definitely wasn't waiting for.

Vitally, this record suffers from no glaring omissions. It draws from both studio albums while gathering essential singles and B-sides that never found a home on a long-player. There are no "lost" demos or grainy bootlegs here, but the record doesn't need them. We know these songs inside out, and the sequencing reflects that confidence.

The tracklist ignores chronological order, allowing the heavy, blues-inflected crunch of 'Second Coming' to sit comfortably alongside the band's earliest jangle-pop singles. 'Love Spreads' snarls defiantly against the bright melody of 'What the World is Waiting For', proving that their second album contained genuine moments of brilliance; it simply had the misfortune of following arguably the most important British debut ever.

The record is bookended by the two pillars of the Roses' mythos. It opens, as it must, with 'I Wanna Be Adored'.

It begins with that iconic, brooding bassline, a low-end thrum that feels like it’s rising out of a Manchester fog. It is a masterclass in atmosphere, a slow-build anthem of pure ego and desire. When Ian Brown’s hushed vocals finally drift in, he isn’t asking for fame; he’s stating a cosmic requirement. It is the definitive opening statement for a band that felt destined for greatness before they’d even played a note.

At the other end of the record lies 'I Am the Resurrection'.

If 'I Wanna Be Adored' is the invitation, this is the transcendence. While 'The Complete Stone Roses' tried to chop it down, here we get the full, sprawling epic. It begins as a defiant break-up song before mutating into a four-minute psychedelic funk workout. Reni’s drumming is untouchable, Mani’s bass is locked in a permanent groove, and John Squire’s guitar work elevates the track into a different stratosphere. It is the sound of a band realising they are exactly as good as they said they were.

The evolution captured on this record isn't just a change in style; it’s the sound of a band learning how to fly. 'Elephant Stone' proves just how good the band were from the get-go.

Produced by Peter Hook of New Order, it serves as the bridge between their scrappy, post-punk roots and the shimmering, "Baggy" psychedelia that would soon define an entire generation. It features a relentless, cascading drum beat from Reni that proved, even then, the Roses had a rhythm section that could dance as well as it could rock. It was a call to arms for every kid in Manchester who was tired of the gloom.

While the guitars often take the spotlight, the true engine was the telepathic connection between Mani’s bass and Reni’s drums. If 'I Wanna Be Adored' is the sunrise, then 'Fools Gold' represents the the sunset, the exact moment where British rock finally surrendered to the dancefloor. Built around a 16-beat loop inspired by 'Funky Drummer', Mani stepped forward with a bassline that was hypnotic and impossibly cool. It proved they were the first indie group to truly understand the chemistry of the Haçienda.

Then there is 'Sally Cinnamon', a song so potent it famously altered the course of British rock history. As Noel Gallagher once put it:

"When I heard 'Sally Cinnamon' for the first time, I knew what my destiny was."

Even the more experimental, later moments find their rightful place here, most notably the sprawling opening of 'Breaking Into Heaven'. If the debut album was about the arrival, this track from 'Second Coming' was about the journey into the wilderness.

The song begins with over four minutes of atmospheric, jungle-noise soundscapes and distant, echoing percussion, a daring, experimental intro that tested the patience of many but rewarded those who stayed for the payoff.

When the heavy, Led Zeppelin-esque riff finally kicks in, it serves as a powerful reminder that even when the band was retreating into the woods of South Wales for those infamous five-year studio stints, their ambition remained massive. They weren't just making songs anymore; they were building walls of sound.

There is an unspoken rule in the music industry that The Beatles invented the very DNA of pop music (they did). Since then, most bands have been content to either imitate them or merely exist in their shadow. The Stone Roses were the rare, arrogant exception. They didn’t just aim for the charts; they aimed for the throne.

They were the ultimate anti-establishment icons, a group that arrived with a manifesto of pure, unshakable self-belief. Whether they were singing about killing the Queen or declaring a generation's love for them before playing a note, "it takes time for people to fall in love with you, but it's inevitable", they carried a conviction that felt cosmic. They didn’t just want to be stars; they wanted to be a religion.

While that total global domination didn't quite materialise in the way they’d planned, the belief itself was transformative. That audacity, the same ego that led Ian Brown to claim they’d eventually play on the moon and be bigger than The Beatles, is what fueled the fire.

That dream may not have fully transpired into the history books, but it did result in arguably the finest collection of singles ever produced by a British band. When you listen to these fifteen songs, it’s easy to see why they felt the earth was too small to hold them.