You either make money, or you make history

'Factory Records' was never just a record label; it was a blueprint for a cultural revolution. It stands as one of the most significant contributions to British popular culture, fundamentally altering how a generation dressed, danced, and dreamed. Through a cast of visionaries and rebels, including Tony Wilson, Ian Curtis, Shaun Ryder, and Martin Hannett, Factory didn't just produce music; it transformed a decaying industrial city into the centre of the creative universe.

Anarchy in the UK- Where it all started.

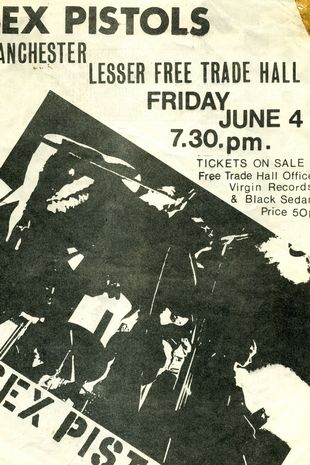

On June 4, 1976, at the Lesser Free Trade Hall, punk finally hit the North. The Sex Pistols were playing their first gig outside of London, an event brokered by Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley, two aspiring musicians who would soon form Buzzcocks, Manchester’s definitive answer to the punk explosion. While the rest of the city remained oblivious to the brewing cultural storm, for the forty or so people in attendance, everything clicked into place.

The audience that night was a roll-call of future legends. Among them was Martin Hannett, then a studio engineer, who would eventually become the sonic architect of 'Factory Records', producing seminal works for Joy Division, Happy Mondays, and The Stone Roses. Also watching were Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, and Bernard Sumner; inspired by the raw energy on stage, they would form Stiff Kittens, then Warsaw, before finally settling on the name Joy Division.

The crowd even included a young Steven Patrick Morrissey, who famously wrote to the NME to express his disdain for the band, and Mark E. Smith, the future mastermind of 'The Fall'. Watching it all with a keen, prophetic eye was Granada TV personality Tony Wilson.

Wilson recognised immediately that punk was a tectonic shift. Despite the sparse turnout, he understood the weight of the moment, later famously quipping: "The smaller the attendance, the bigger the history. There were twelve people at the Last Supper."

The Sex Pistols at the Lesser Free Trade Hall was the spark Manchester required. In that miserable, bleak, and cold Northern city, punk didn't just find an audience; it found its spiritual home.

So it Goes- Tony Wilson

Inspired by the Sex Pistols at the Free Trade Hall, Tony Wilson launched 'So It Goes', a music program on Granada Television designed to rival the BBC’s 'Top of the Pops'. The show became a vital platform for the underground, providing the first TV appearances for the likes of the Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks, The Clash, The Jam, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Patti Smith. Wilson was among the first to grasp the gravity of this new genre, but broadcasting it to the masses wasn't enough. He wanted to be at the heart of the creation itself.

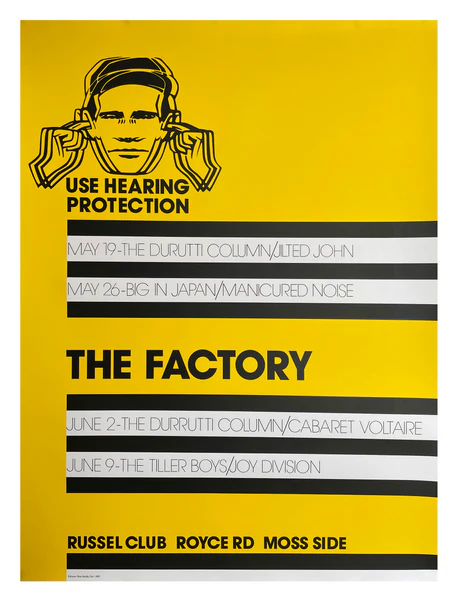

The success of 'So It Goes' led Wilson and his friends Alan Erasmus and Alan Wise to establish a club night at Moss Side’s Russell Club. They called the night 'The Factory'. It was here that several major figures in the story first emerged; acts like The Durutti Column, Joy Division, Cabaret Voltaire, and The Tiller Boys all graced the Russell Club stage. This period also marked the arrival of Peter Saville, the visionary designer responsible for the label's legendary aesthetic.

Crucially, this was the birth of the catalogue system. 'FAC 1' was the designation given to the very first event poster. This system of assigning a unique number to every Factory-related item became a hallmark of the label, and, as the years went on, the assignments would only get stranger.

Driven by a desire to capture the energy of the Russell Club on vinyl, Factory Records was born. Wilson and Erasmus partnered with Joy Division’s manager, Rob Gretton, and the mercurial producer Martin Hannett. None of them could have foreseen the cultural earthquake they were about to trigger.

Factory Records was fundamentally different from any label before or since. Wilson’s philosophy was built on total creative freedom, famously granting his artists "the freedom to fuck off." There were no formal contracts; the label owned nothing, and the artists owned everything. The only legal document of the venture’s existence was a manifesto stating exactly that, famously signed in Tony Wilson’s own blood. This was never going to be a simple business venture; it was a radical experiment in art and autonomy.

Radio Live Transmission- Joy Division

Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, and Bernard Sumner had all been at the legendary Sex Pistols show at the Lesser Free Trade Hall. Along with Stephen Morris, they eventually evolved into Joy Division. As regulars at 'The Factory' nights hosted by Tony Wilson, and with their manager,r Rob Gretton, now a partner in the label, it was inevitable that Joy Division would become the flagship band for Factory Records.

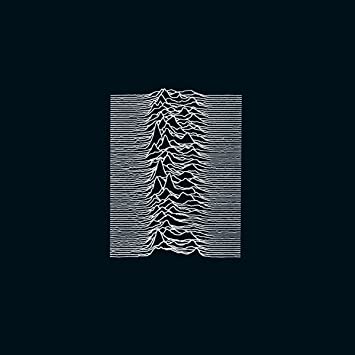

The band began recording their debut album, 'Unknown Pleasures', at Stockport’s Strawberry Studios in the spring of 1979. Behind the glass was Martin Hannett, a man whose eccentric brilliance would define the Factory sound. We can thank Hannett’s "madness" for the atmospheric weight of the record; his process was anything but conventional. Drum kits were dismantled and reassembled on the studio roof, and Ian Curtis’s vocals for 'Insight' were famously recorded through a telephone line to achieve a distant, haunting effect. Hannett ripped up the rulebook, stripping away the band’s raw punk edges to reveal something far more industrial and cold.

The album featured 'She’s Lost Control', a visceral track inspired by a young woman Curtis met through his work as a rehabilitation officer. To achieve its distinct, mechanical percussion, Stephen Morris famously used an aerosol spray can as an instrument. 'Unknown Pleasures' was a sonic map of 1970s Manchester: dark, bleak, and cavernous. Peter Saville provided the finishing touch with his iconic cover art, featuring the wave plotting of a pulsar. Released as 'FAC 10', the album became a masterpiece of both music and design, cementing Hannett and Saville as the premier architects of their era.

With 'Unknown Pleasures', the band ushered in the Post-Punk movement. They soon followed this with the driving, hypnotic single 'Transmission', a track so powerful that Peter Hook recalled people stopping in their tracks just to watch them play it. They also recorded the ethereal 'Atmosphere', a masterclass in mood that felt like a funeral march, originally released as a limited single titled 'Licht und Blindheit'.

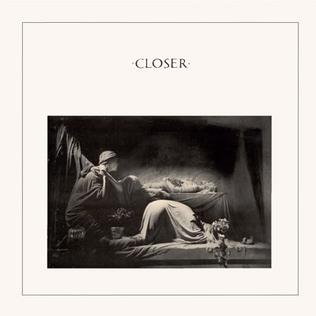

The band expanded their sound further with their second album, 'Closer', in 1980. However, the story took a tragic turn. In May 1980, on the eve of the band’s first American tour, Ian Curtis took his own life. Struggling with severe epilepsy, the debilitating side effects of his medication, and deep personal turmoil, the world lost a true genius. 'Closer' was released posthumously two months later, serving as a stark, beautiful final statement. Around this time, the band also released their most famous song, 'Love Will Tear Us Apart'. A definitive anthem of the era, the lyrics were a painful reflection of Ian’s failing marriage, recorded just months before his death.

Following Curtis’s suicide, the remaining members felt they could not continue under the same name. Factory Records had lost its brightest spark, but the "do-it-yourself" attitude the band embodied remained the cornerstone of the label. Joy Division’s impact cannot be understated; their music lived on, their artwork became a global cultural shorthand, and they remained the catalyst for everything Factory would do next.

I'll Find My Soul as I Go Home- New Order

New Order rose like a phoenix from the ashes of Joy Division. While Hook, Morris, and Sumner felt a desperate need to continue, they refused to do so under their former name, choosing instead to start anew. The impact of New Order is almost impossible to quantify; they didn't just change their sound, they altered the British musical landscape overnight, eventually handing Factory its only number one single and helping to position Manchester as the centre of the musical universe.

The band’s debut album, 'Movement', released as 'FAC 50' in 1981, was produced by Martin Hannett. It would be his final collaboration with the group. Struggling with the loss of Ian Curtis and spiralling into heavy drug use, Hannett became increasingly difficult to work with. While 'Movement' served as a bridge from their post-punk roots, it was with their second album, 'Power, Corruption & Lies', that they finally stepped out of Joy Division’s shadow.

Before that album arrived, however, the band released an era-defining 12-inch single: 'Blue Monday' ('FAC 73'). This track saw New Order abandon the gloom of post-punk for the neon pulse of the dancefloor. Embracing New York club culture through an industrial Mancunian lens, 'Blue Monday' became synonymous with Factory Records. Everything about it was iconic, from its futuristic synthesisers to Peter Saville’s die-cut sleeve designed to look like a floppy disk. Famously, the packaging was so expensive to produce that Factory lost 10p on every copy sold, a financial disaster only compounded by the fact that it became the best-selling 12-inch single of all time.

The transition continued with 'Power, Corruption & Lies' ('FAC 75'), an album many fans still consider the band's peak. Working without Hannett for the first time, the group collaborated with engineer Mike Johnson to develop a sound that balanced new technology with their signature melancholy. The record featured classics like 'Age of Consent', 'Leave Me Alone', and the majestic 'Your Silent Face'. Saville’s cover art, based on Henri Fantin-Latour’s painting 'A Basket of Roses', became one of the label's most recognisable images.

By 1985, the band reached another career high with 'Low-Life' ('FAC 100'), which effortlessly fused rock and synth-pop. It included the fan favourite 'The Perfect Kiss' and the underrated guitar anthem 'Love Vigilantes'. A year later, 'Brotherhood' ('FAC 150') split the band's identity between their electronic and rock leanings. It contained 'As It Was When It Was', described by Peter Hook as a vision of Manchester at its bleakest, and 'Bizarre Love Triangle', a bright look toward the band's future pop direction.

In 1987, Factory released the compilation 'Substance' ('FAC 200'). Legend has it that the collection was curated simply so Tony Wilson could listen to all the band’s non-album singles in his car. Because New Order often released 12-inch singles that never appeared on LPs, 'Substance' became an essential archive of masterpieces like 'Ceremony' ('FAC 33'), 'Temptation' ('FAC 63'), 'Thieves Like Us' ('FAC 103'), and 'True Faith' ('FAC 183').

The band’s first number one album arrived in 1989 with 'Technique' ('FAC 275'). Recorded partly during what Tony Wilson called "the most expensive holiday ever" in Ibiza, the Balearic influence is undeniable on tracks like 'Fine Time' and 'Vanishing Point'. However, the album was finished at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios in Bath, where the high-tech environment allowed the band to reach their creative peak.

By 1990, New Order was on the verge of a breakup due to constant infighting. Despite the hiatus, Tony Wilson volunteered the band to record England's official World Cup song for 'Italia '90'. The result was 'World in Motion', a track featuring a rap by footballer John Barnes and lyrics by comedian Keith Allen. Far from a novelty gimmick, it was a genuine pop triumph and gave New Order their first and only number one single. It was the peak of mainstream success that summarised the beautiful unpredictability of Factory Records.

The final New Order album released under the label was 1993’s 'Republic' ('FAC 300'). Recorded during a turbulent era for both the band and the company, it was an album intended to save Factory from bankruptcy. Stephen Morris later admitted he found the record difficult to listen to objectively. While it yielded 'Regret', perhaps the last truly great New Order single of the Factory era, it remains a bittersweet chapter in the story, marking the end of a label that had changed the world.

Everything Starts With An E- The Hacienda

In 1982, Factory Records stood at a crossroads. Producer Martin Hannett urged the label to build a professional recording studio, believing it would pay for itself after a single album (a prediction that would eventually prove correct). However, Factory chose a more radical path. After witnessing the vibrant New York club scene during a 1981 tour, New Order and Rob Gretton were determined to bring that energy back to Manchester.

The result was 'FAC 51'. The mantra was simple: "The Hacienda must be built."

The club was a joint venture, with New Order and Factory Records each owning 50%. This meant the band was directly subsidising the dream. For Martin Hannett, it was the final straw; he quit the label after discovering that £450,000, money he felt belonged in the recording budget, had been diverted to the club’s construction. Factory had lost a founding visionary, and its financial woes were only beginning.

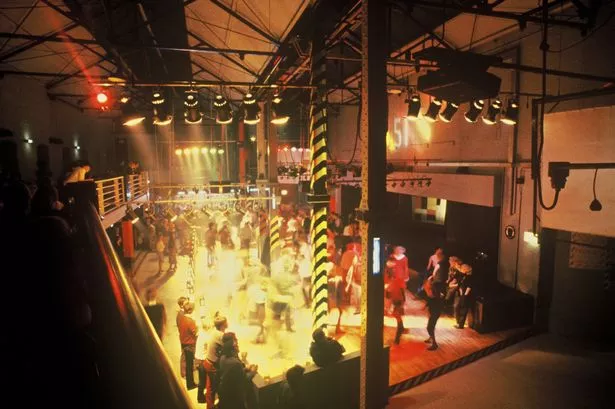

Designed by architect Ben Kelly, the interior was a bold, industrial take on New York chic, filled with hazard stripes and high-tech aesthetics. In its infancy, the cavernous space often felt empty and cold, but it became a vital stage for rising talent thanks to chief booker Mike Pickering. In February 1983, The Smiths performed there immediately after a performance on 'Top of the Pops'; staggeringly, it was only their third gig together. You can watch that legendary performance here

The Hacienda became a cathedral for the underground. New Order gave 'Blue Monday' its first live outing there in January 1983, and the club hosted future giants on the cusp of fame: Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses, and even Madonna in 1984. On September 5, 1994, Oasis would play the venue to promote 'Definitely Maybe'. While not everyone was signed to the label, the club acted as a forge for their careers.

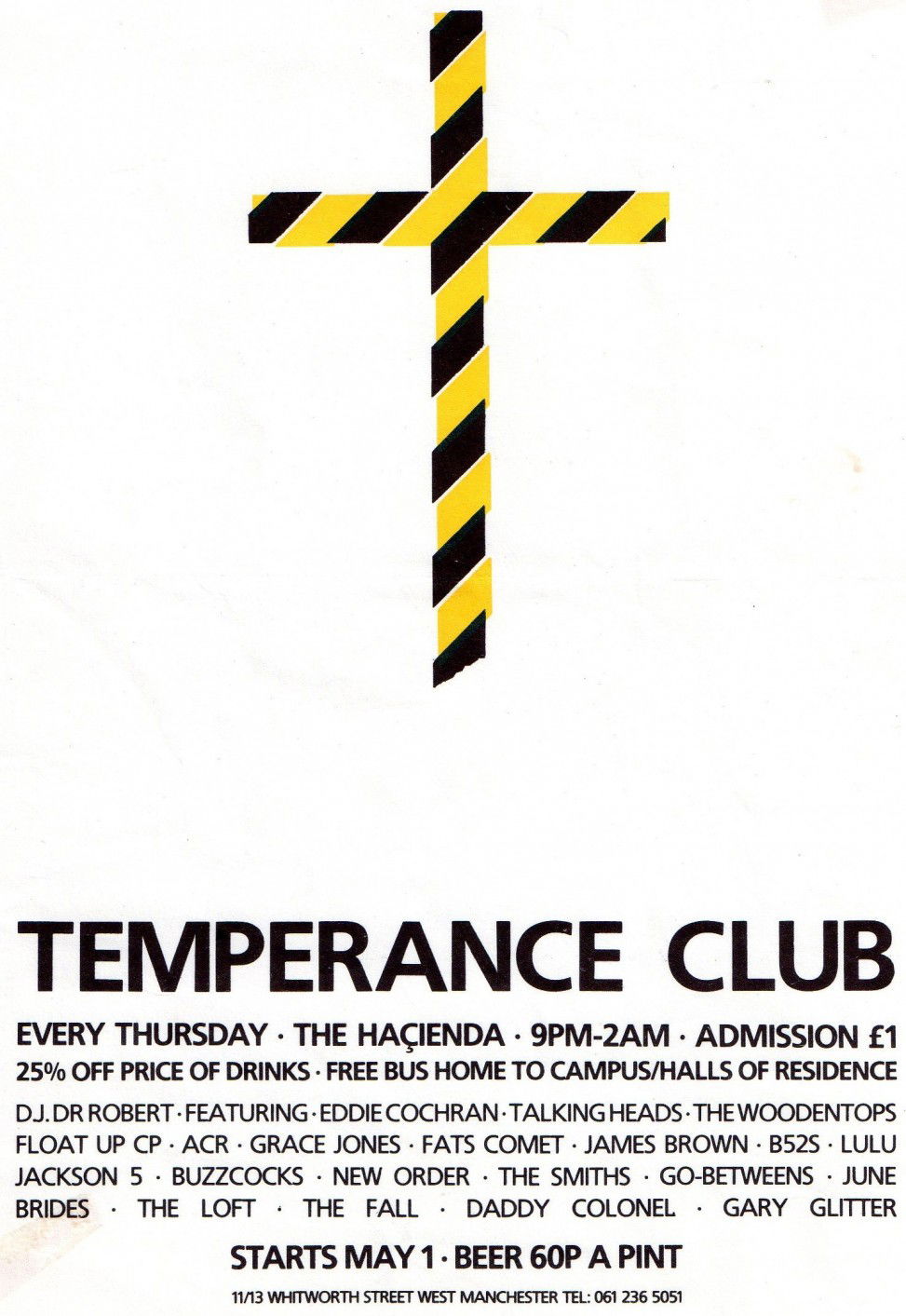

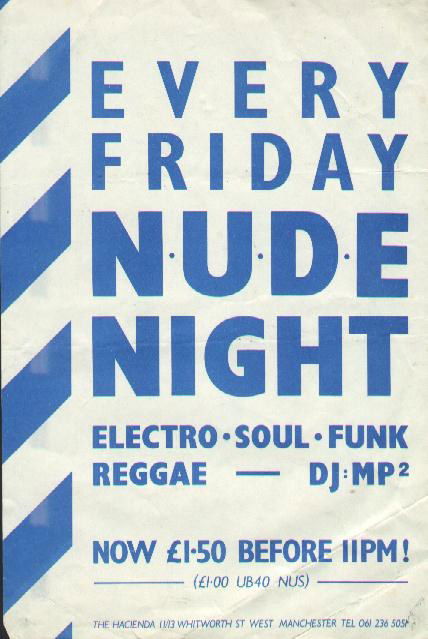

By 1986, however, the venue was a "white elephant" bleeding money. Peter Hook famously remarked that the band would have been better off giving ten pounds to everyone who approached the club and telling them to go home. That changed almost overnight with the arrival of DJs like Mike Pickering, Graeme Park, Dave Haslam, and Jon Da Silva. They pioneered nights like 'Nude' and 'Temperance', introducing Manchester to a new sound: House music, which soon mutated into Acid House.

This musical shift coincided with the emergence of Ecstasy. The drug transformed the dancefloor, fostering a sense of community that defied the divisive, bleak landscape of Thatcher’s Britain. It was here that Noel Gallagher had his first drug-fueled epiphany; he later noted that The Hacienda was the first place he ever danced. Manchester began producing its own anthems for this era, most notably 808 State’s 'Pacific State' and A Guy Called Gerald’s 'Voodoo Ray'.

The Hacienda essentially birthed the modern superclub and the underground rave movement, but its success carried a heavy price. While the "E" sparked a revolution, it killed alcohol sales; the club notoriously became the UK’s biggest seller of bottled water. More tragically, the drug trade attracted Manchester’s underworld. On July 14, 1989, 16-year-old Clare Leighton collapsed and died at the club, the UK’s first Ecstasy-related death.

The ensuing years were marred by police crackdowns and escalating gang violence, including stabbings and shootings. Mike Pickering eventually resigned, and despite its cultural peak between 1987 and 1989, the financial and security burdens became insurmountable. The Hacienda closed its doors forever in 1997.

Its legacy remains monumental. It helped birth the "Madchester" movement, provided a home for the burgeoning LGBTQ+ scene with nights like 'Flesh', and fundamentally changed the DNA of British pop culture.

Hallelujah- The Happy Mondays & Madchester

One of Factory’s most successful acts was Happy Mondays, a band that became synonymous with the glory days of 'The Hacienda'. They first appeared on Tony Wilson’s radar after coming dead last in a "battle of the bands" competition at the club, yet he signed them anyway. By 1987, as Acid House was emerging, the Mondays began blending danceable grooves with their own brand of ramshackle guitars and drums to create a truly unique sound.

Their debut album, 'Squirrel and G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out)', was released in 1987. Produced by John Cale of Velvet Underground fame, it featured the singles 'Tart Tart' and '24 Hour Party People'. Manchester had a new force to reckon with, and they were only just getting started.

The follow-up, 'Bummed', arrived a year later. It was produced by Martin Hannett, who, despite no longer being a formal partner in the label, continued to lend his genius to Factory artists. Happy Mondays were unlike anything else on the roster; they lacked the polished glamour of New Order or the avant-garde variety of A Certain Ratio, but that raw edge is exactly what drew Wilson to them. 'Bummed' proved his instincts right, delivering classic tracks like 'Performance' and the hypnotic 'Wrote for Luck'.

In 1989, Manchester officially transformed into "Madchester." The movement was spearheaded by two bands: The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays. While the Roses released their seminal self-titled debut, Happy Mondays released the 'Madchester Rave On' EP, featuring a club mix of 'Hallelujah'. Remixed by Paul Oakenfold and Steve Osborne, the track became a defining anthem of the era.

The cultural peak occurred on November 30, 1989, when both bands appeared on 'Top of the Pops' on the same night. The Stone Roses performed 'Fools Gold' while Happy Mondays played 'Hallelujah' alongside special guest Kirsty MacColl. It was the "Second Summer of Love," and Manchester was the centre of the universe. With the best bands, the best nightclub, and the best records, Factory Records sat firmly at the heart of the explosion.

By 1990, the band released 'Pills 'n' Thrills and Bellyaches', a masterpiece that perfectly fused indie-rock with dance melodies. Shaun Ryder’s surreal, street-poet lyrics were so impactful that Tony Wilson famously compared him to W.B. Yeats. The album was a high-water mark for the group, featuring the massive hits 'Step On' and 'Kinky Afro'. It also included 'God’s Cop', a sardonic swipe at the hardline Chief Constable James Anderton, who was notoriously aggressive toward rave culture. With lyrics like "God laid his E's all on me," the song captured the spirit of the band and the era perfectly.

The "Baggy" scene was in full flow. Manchester wasn't just an indie scene anymore; it was a global phenomenon. People everywhere were dressing, talking, and walking like Mancunians. Noel Gallagher famously recalled The Sun even running a guide on how to "talk Mancunian." Factory Records had successfully turned a local subculture into the dominant force in popular music.

However, the high was about to lead to a devastating crash. It is often said that while New Order built the Factory empire, Happy Mondays tore it down. By 1991, despite their massive success, the band was spiralling. Shaun and Paul Ryder were struggling with heroin addiction, and in a desperate attempt to get them to record a new album, the label shipped them to Barbados. The logic was that the island had no heroin, but it happened to be a hub for crack cocaine. The band quickly became addicted, famously selling studio equipment to fund their habits.

The sessions were a catastrophe. Upon returning to England, Shaun allegedly held the master tapes for ransom, a legendary moment later dramatised in the film '24 Hour Party People'. When Factory finally recovered the tapes, they discovered there were no vocals recorded at all.

By the time the resulting album, 'Yes Please!', was finally finished and released in 1992, the Madchester dream was over. The musical tide had turned toward the grunge sounds of Seattle, and the label that had defined a decade was facing its final curtain call.

Don't Walk Away in Silence- The End

By late 1992, Factory Records was struggling for survival. The Haçienda was a constant drain on funds, the Barbados sessions for 'Yes Please!' had been a financial catastrophe, and the label was still waiting on a new New Order album to balance the books. Following the expensive production of 'Technique' in 1989, the label simply had no more capital, and with nothing left to release, the money ran out.

The label’s radical punk ethos and legendary lack of contracts ultimately proved to be its undoing. When London Records expressed interest in buying the company, the deal collapsed because of the very manifesto Tony Wilson had signed in his own blood. Because Factory owned no rights to the artists’ work, including their biggest asset, New Order, there was nothing for a buyer to actually purchase.

On November 22, 1992, Factory Records was declared bankrupt. Five years later, on June 28, 1997, 'The Haçienda' closed its doors for the last time.

It wasn't the ending the partners had envisioned, but they had achieved something far greater than financial stability: they had never sold out. As the first true independent powerhouse, Factory changed the musical landscape forever. They formed a counter-culture and gave a decaying city a new identity.

The impact of Factory Records is woven into the very fabric of Manchester. Without them, it is unlikely that The Smiths or The Stone Roses would have reached such heights. The indie labels of the 90s, like 'Creation Records' and 'Food Records', owed their existence to the Factory blueprint.

Without those, there would be no Oasis and no Blur. The lineage of British rave culture began when Mike Pickering, Graeme Park, and Dave Haslam first played House music to UK audiences. Meanwhile, New Order and Happy Mondays successfully bridged the gap between indie-rock and the dancefloor, creating music you could finally dance to.

Even beyond the giants, the label was home to hidden gems like Section 25, The Durutti Column, A Certain Ratio, and Quando Quango, each with a unique sound that contributed to the rise and fall of the empire.

Through it all, the label maintained its peculiar sense of humour, best seen in the catalogue system. It wasn't just music that received a number; 'FAC 61' was the lawsuit between Martin Hannett and the label, 'FAC 83' was a birthday party, 'FAC 99' was Rob Gretton’s dental surgery, and 'FAC 401' was the brilliant film '24 Hour Party People'. Most poignantly, 'FAC 501' was assigned to Tony Wilson’s own funeral.

From the early gigs at the Russell Club to the final days of 'Republic', Factory Records was the most influential independent label in history. It was a 14-year run fueled by civic pride and an unwavering faith in art. It revolutionised the industry and redefined how generations of musicians think.

To quote the man at the centre of the storm:

"Most of all, I love Manchester. The crumbling warehouses, the railway arches, the cheap, abundant drugs. That's what did it in the end. Not the money, not the music, not even the guns. That is my heroic flaw: my excess of civic pride." — Tony Wilson

Thank you for reading, and remember: "When forced to pick between truth and legend, print the legend."

For Tony Wilson, Ian Curtis, Martin Hannett, Rob Gretton, Joe, and finally Manchester and all those who have and do call it home.