We Did Believe The Hype

On the 23rd of January 2006, Alex Turner uttered these famous words. “We’re Arctic Monkeys, this is ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’, don’t believe the hype.” But as the band's debut turns 20 on the 29th January, it's clear that despite his warning, the public did believe the hype and for very, very good reason.

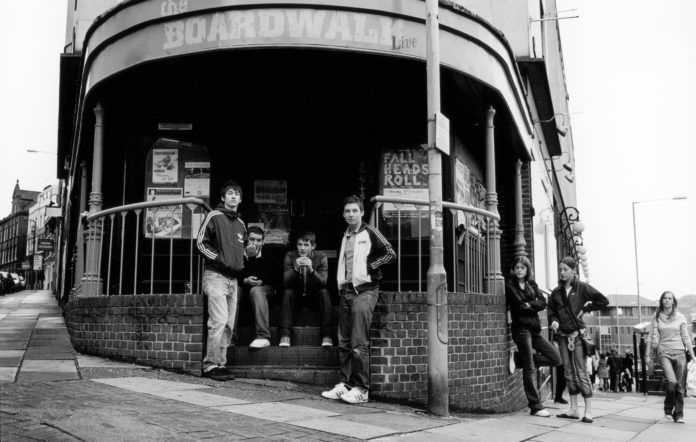

The Legend of 'Beneath the Boardwalk

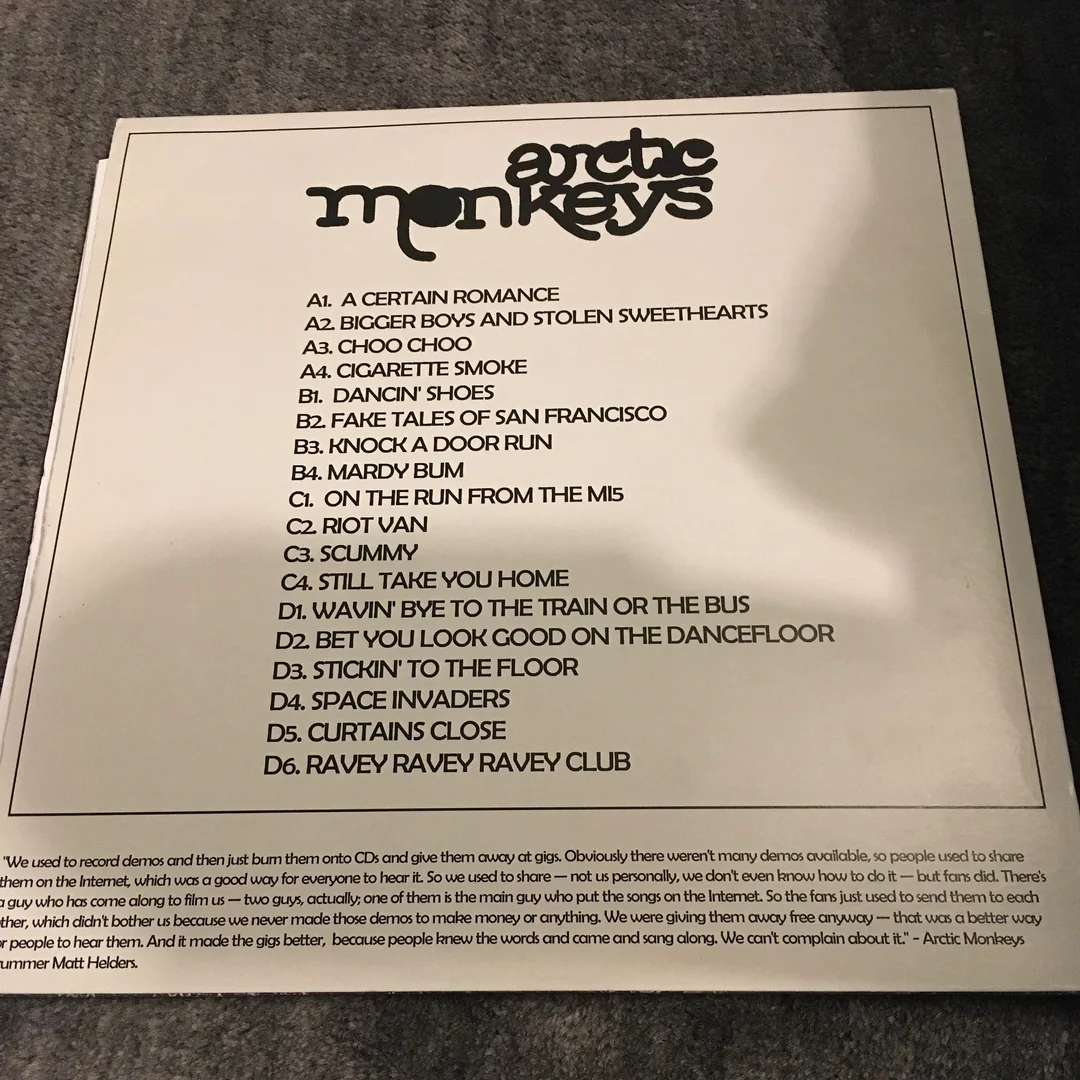

Before the album became a physical reality, it was a digital ghost. The 'Beneath the Boardwalk' collection, a compilation of 18 demo tracks, is perhaps the most significant "unofficial" release in British music history. Handed out for free on burned CDs at gigs at the Sheffield Grapes, these tracks were ripped and uploaded to the internet by fans.

This grassroots movement bypassed the traditional gatekeepers of the music industry. By the time the band signed to Domino, the songs on 'Beneath the Boardwalk' had already been memorised by thousands. It wasn't just a demo tape; it was a blueprint for the future of music distribution, proving that if the songs were good enough, the fans would find them.

Of the 13 tracks that eventually formed the tracklist for 'Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not', seven of them had their origins in the 'Beneath the Boardwalk' sessions.

The following songs were part of the original 'Beneath the Boardwalk' collection but were either relegated to B-sides, appearing on later EPs, or left in the archives:

- 'Bigger Boys and Stolen Sweethearts': A fan favourite that eventually became the B-side to 'I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor'.

- 'Cigarette Smoker Fiona': This was re-recorded and shortened to 'Cigarette Smoker' for the 'Who the Fuck Are Arctic Monkeys?' EP.

- 'Despair in the Departure Lounge': Another track that found its home on the 'Who the Fuck Are Arctic Monkeys?' EP.

- 'No Buses': A gentler, melodic track that also landed on the same 2006 EP.

- 'Choo Choo': A very early rarity that never saw an official studio release.

- 'Knock a Door Run': A high-tempo track that remains a demo-era exclusive.

- 'On the Run from the MI5': A fast-paced demo that didn't make the transition to the studio album.

- 'Curtains Close': A rare early track that showed the band's more garage-rock roots.

- 'Space Invaders': A short, frantic blast of energy that stayed as a demo.

- 'Wavin' Bye to the Train or the Bus': Another early observational track that remains a rarity

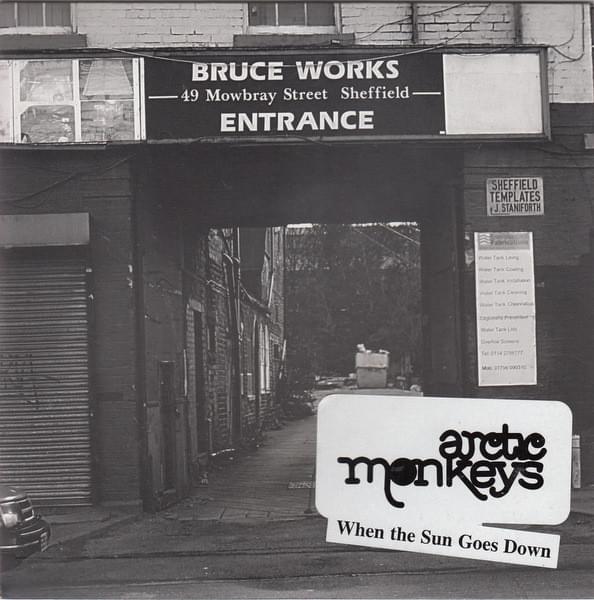

When the band went into the studio with producer Jim Abbiss to record the album, they decided to trim the fat. Tracks like 'Scummy' were polished into 'When the Sun Goes Down', and new songs that weren't on the original demo like 'The View from the Afternoon' and 'The Ritz to the Rubble' were written to complete the narrative of a night out in Sheffield.

The transition from the rough, "clattery" sound of 'Beneath the Boardwalk' to the tight, punchy production of the debut is exactly what the NME meant when they described it as having the "clatter of The Libertines" mixed with the "melodic nous of The Beatles."

Two Number Ones

The album's meteoric rise was fueled by two singles that went straight to the top of the UK charts, each capturing a different side of the band's prowess:

'I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor': This was the opening salvo that changed everything. A frantic, garage-rock explosion, it served as a critique of the shallow "see and be seen" culture of nightclubs. Turner’s lyrical bite is sharp here; he isn't just watching the dancefloor, he’s dissecting it. A perfect example of his witty wordplay is the line, “Your name isn’t Rio, but I don’t care for sand,” a direct and cheeky reference to Duran Duran’s ’80s hit 'Rio'. Combined with the famous "1984" reference, it perfectly captured the sweat-soaked energy and intellectual sharp-edgedness of a crowded indie floor.

'When the Sun Goes Down': Originally titled 'Scummy' on the 'Beneath the Boardwalk' demos, this track showed Turner’s storytelling maturity. It begins as a delicate acoustic lament before crashing into a heavy, cautionary tale about the dark underbelly of Sheffield’s Neepsend district, specifically focusing on the grim reality of solicitation and prostitution. The shift from the gentle opening to the aggressive riff mirrors the sunset itself, the moment the city turns dangerous. Turner handles the heavy subject matter with a mix of empathy and street-level grit, proving he could write about the "scumbags" and the vulnerable with equal precision.

A Tracklist of Modern Classics

Turner’s pen didn't miss across the entire record, documenting the mundane and the monumental with poetic flair:

'Fake Tales of San Francisco': Another 'Beneath the Boardwalk' staple, this track was the ultimate "call out" to bands who traded their own identities for a faux-American aesthetic. Turner’s wit shines as he skewers a local act: "He talks of San Francisco, he's from Hunter's Bar / I don't quite know the distance, but I'm sure that's far."

He even takes a swipe at the enablers of bad music with the brilliant couplet: "Yeah, but his bird said it's amazing though / So all that's left is the proof that love's not only blind but deaf." It was a rallying cry for being unashamedly yourself. It's still a sensational piece of music.

Mardy Bum': A fan favourite that shifted the tone from the aggressive to the melodic. It’s a beautifully relatable kitchen-sink drama about a relationship hitting a rocky patch. Turner’s ability to use colloquialisms like "right hard to remember" and "cuddles in the kitchen" turned a simple domestic argument into a soaring, bittersweet anthem that felt like it belonged to everyone.

The rest of the record maintains this breathless quality, weaving a narrative of a single, chaotic night out. ‘The View from the Afternoon’ kicks the door down with Matt Helders’ iconic drumming, setting the pace for stories of aggressive bouncers in ‘From the Ritz to the Rubble’ and the desperation of the "weekend rockstars" in ‘Still Take You Home’.

Even the quieter moments carry weight. ‘Riot Van’ provides a haunting, slowed-down perspective on run-ins with the police, while ‘Red Light Indicates Doors Are Secured’ captures the frantic, drunken logic of a taxi ride home. Each track—from the punchy ‘You Probably Couldn't See for the Lights, but You Were Staring Straight at Me’ to the biting ‘Perhaps Vampires Is a Bit Strong But...’ contributes to a record that feels like a lived-in, sweat-soaked reality.

‘A Certain Romance’: As perfect a pop song as you could ever hope to hear, it rivals even The Streets in its portrayal of small-town England, a place where “there’s only music so that there’s new ringtones.” Alex’s message is compact yet delivered with dazzling poetic flair: “All of that’s what the point is not / The point’s that there ain’t no romance around here.”

Is there anything at all romantic about outgrowing your hometown? As your teenage years draw to a close, the overfamiliarity of your locale can feel increasingly claustrophobic, but a nagging undercurrent of pride is what draws you back. What ‘A Certain Romance’ offers is a small victory. With no real chorus and very few rhythmic changes, it manages to condense the bombast and tension of the universal suburban adolescence into five life-affirming minutes. No other song feels more searing; it’s the sound of believing in a band’s every word. As it builds to an earth-shaking climax (“Well, you won’t get me to go / Not anywhere, not anywhere…”), Jamie Cook’s guitar roars and Helders’ drums coalesce with Turner’s double epiphany—there is no place like home, and there is no band like Arctic Monkeys.

Impact: Then and Now

In 2006, the impact was a shock to the system. The record became the fastest-selling debut album in British music history at the time, shifting over 360,000 copies in its first week. As NME famously noted:

"Essentially this is a stripped-down, punk rock record with every touchstone of Great British Music covered: The Britishness of The Kinks, the melodic nous of The Beatles, the sneer of Sex Pistols, the wit of The Smiths, the groove of The Stone Roses, the anthems of Oasis, the clatter of The Libertines…"

At the time, the album represented a paradigm shift in the industry. It was the moment the "gatekeepers" lost their keys; the Monkeys didn't need a massive marketing budget or a slot on Top of the Pops to become the biggest band in the country. They had the internet, and they had authenticity.

The album’s success essentially provided the blueprint for the "indie explosion" of the late 2000s. It paved the way for bands like The Enemy, The View, and The Pigeon Detectives, all of whom leaned into that high-octane, observational style. However, its influence goes much deeper than just the immediate "landfill indie" era

Its influence goes much deeper than just the "landfill indie" era. It permitted artists like Lily Allen, Kate Nash, Blossoms, Sam Fender, and even hip-hop artists like Dave to keep their regional accents thick and their slang local. Catfish and the Bottlemen’s ‘The Balcony’ captures that same youthful, nocturnal urgency, while Foals and Bombay Bicycle Club were given commercial breathing room because the Monkeys had made guitar music the dominant force in the UK again.

Its legacy is found in every artist who prioritises storytelling over artifice and every band that realises their local pub is just as valid a setting for a masterpiece as the streets of New York or LA.

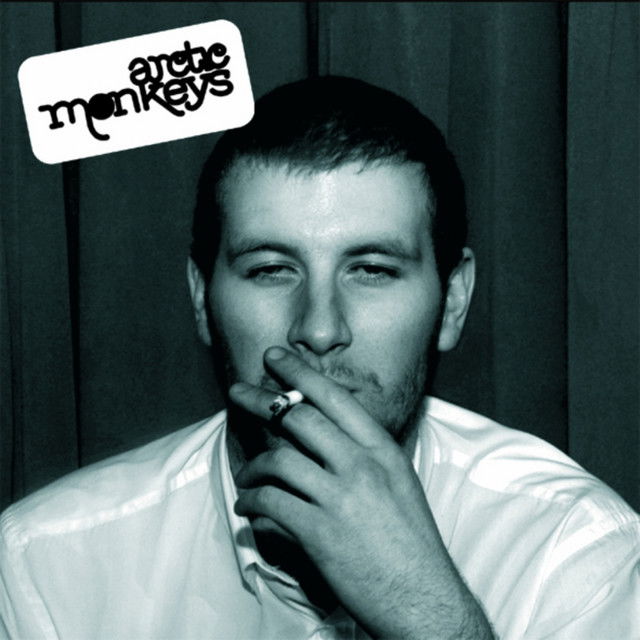

The Iconic Cover

The cover, featuring a candid, smoke-shrouded photo of Chris McClure, remains the perfect visual shorthand for the sound: gritty and intensely real. Chris is famously the brother of Jon McClure, the frontman of fellow Sheffield legends Reverend and The Makers. The backstory of the image is as rock-and-roll as the music itself; Chris was tasked with going out and getting drunk, and the photo was taken in the early hours of the morning at the Korova bar in Liverpool.

The band had given him, his cousin, and his best friend £70 to spend on a night out to ensure they captured that authentic "end of the night" exhaustion. Little did he know he would become the face of one of the most iconic and most important British albums ever. While Chris was reportedly paid only £75 for the shoot, plus that legendary free night out, he earned permanent residence in the pantheon of rock icons. As the face of arguably the best debut album by a British band ever

Conclusion: Two Decades On

Twenty years on, ‘Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’ remains a peerless time capsule of British youth. It isn't just a record about being nineteen; it’s a record that sounds like the very concept of potential. While the band has since evolved into desert-rock crooners and lounge-pop explorers, trading the tracksuit for the tailored suit, this debut remains their foundation. It was a lightning-in-a-bottle moment where the songwriting was too sharp, the drums too fast, and the buzz too real to ignore.

The album’s true magic lies in its survival. In an era of disposable digital content, these songs have become permanent fixtures of the British songbook. They are shouted back at the band in sold-out stadiums from Glastonbury to Rio, proving that Turner’s hyper-local observations of Sheffield nights were, in fact, universal. It’s a record that refuses to grow old; every year, a new crop of teenagers discovers ‘Mardy Bum’ or ‘A Certain Romance’ and finds their own lives reflected in the lyrics, proving that the awkwardness of adolescence and the thrill of a Friday night are timeless.

It still sounds like the first time you stayed out too late, the first time a bouncer ruined your night, and the first time you realised your hometown was both a prison and a palace. Arctic Monkeys didn't just give a generation a voice; they gave them a legend to carry with them. Alex Turner was right about everything, except the warning to ignore the hype. We were right to believe it then, and twenty years later, we are still believing it now.