Through the 'Looking Glass': The Story of The La's

The story of The La’s is one of rock’s most enduring enigmas: a jagged masterpiece of brilliant songwriting, sonic obsession, and self-destruction. It is a chronicle defined by a staggering lack of proportion: twelve separate studio sessions, seven different producers, twenty-four revolving band members, and a million-pound debt, all for the sake of just one album.

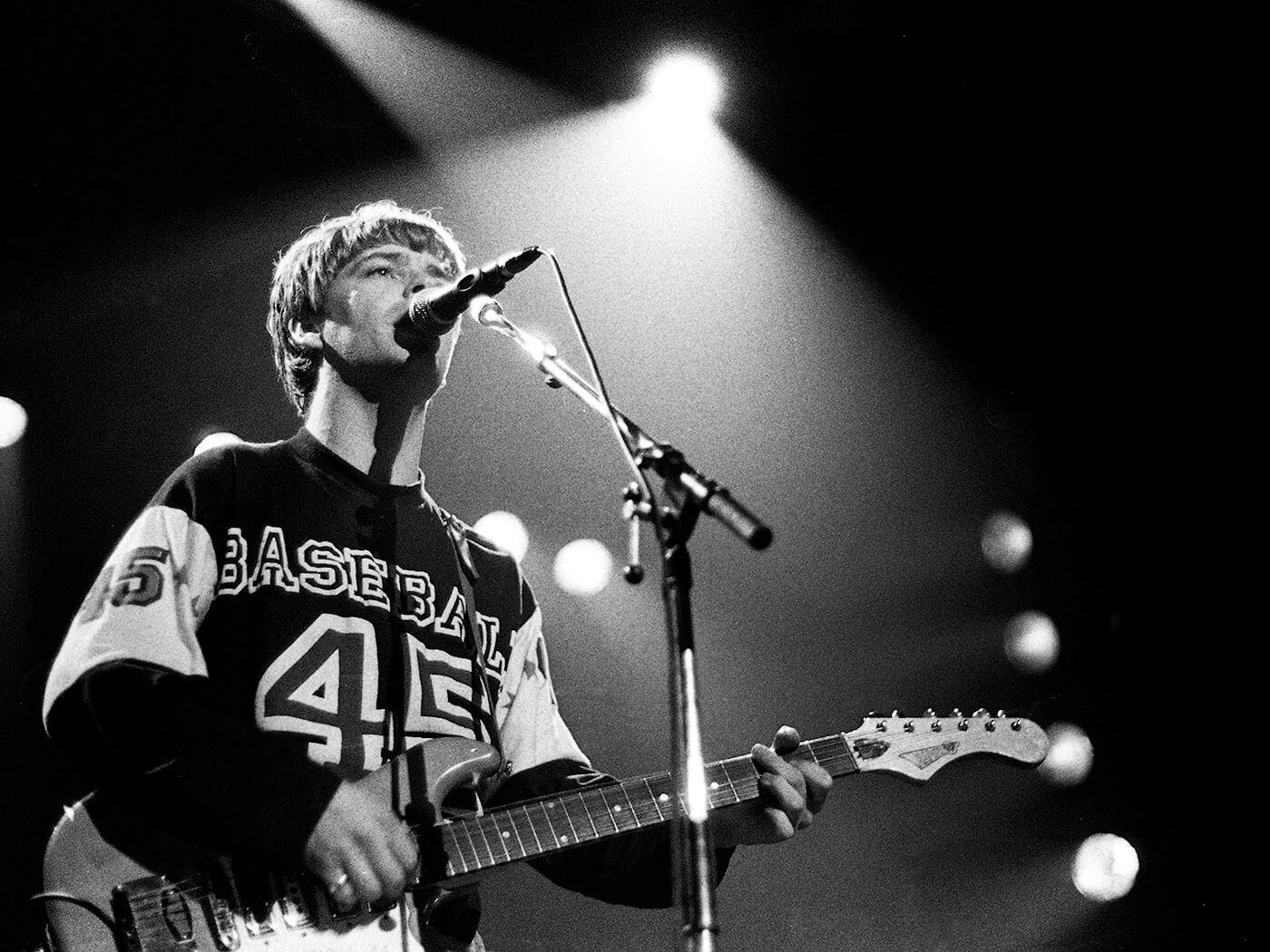

Emerging from Liverpool with a sound that felt both ancient and brand new, the band seemed destined to lead a guitar-pop revolution. Yet, the road to their 1990 debut, ‘The La’s’, was paved with relentless friction. At the heart of the storm was Lee Mavers, a frontman who wasn't merely looking for a good recording, but chasing a phantom frequency, a quest for 1960s dust and an authentic vibration that modern technology seemed determined to kill.

The result was a record that has been mythologised beyond belief by fans and critics alike, hailed as the blueprint for Britpop. But in a final, characteristic twist of irony, it is an album that its own creator famously disowned. This is the story of how a collection of perfect songs, including the timeless ‘There She Goes’, became a source of lifelong haunting for the man who wrote them. It is a journey through the looking glass of perfectionism, where the closer the band got to the truth, the further they drifted from the world.

Formation & Early Days: 1983 to 1986

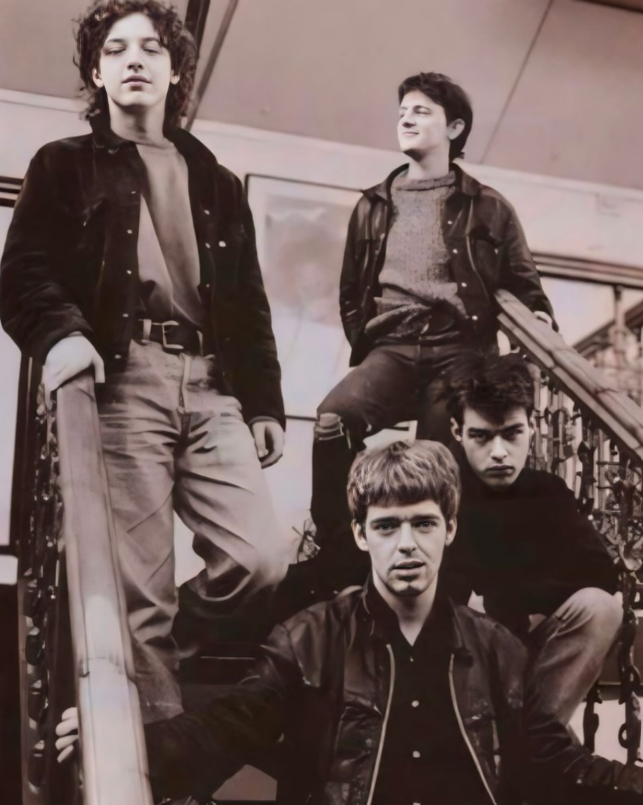

The La’s were born in 1983, the brainchild of Liverpudlian Mike Badger. The moniker, Badger claimed, arrived with the clarity of a dream; a play on the local Scouse slang "La," shorthand for "lad." In its infancy, the group was a sprawling, bohemian experiment, an arthouse-skiffle outfit that traded in raw energy and eccentric rhythm. Badger was the architect and primary songwriter, but in 1984, the band’s trajectory shifted forever when he recruited a local guitarist named Lee Mavers.

Initially brought in to play rhythm, Mavers possessed a burgeoning songwriting talent and a singular intensity that quickly began to reshape the band’s DNA. The lineup was solidified by Bernie Nolan, a seasoned musician from the local circuit, on bass. By 1986, John Power joined the fold after meeting Badger on a council-run musicianship course. However, the chemistry was volatile. As Mavers emerged as a powerhouse songwriter, a power struggle for the soul of the band ensued. Badger’s art-school leanings were slowly being eclipsed by Mavers’s obsessive pursuit of the perfect melody.

The tension reached a breaking point in late 1986. Reflecting on the split in a 2021 BBC interview, Badger recalled the bluntness of the takeover: "We'd done all of the work, and that's when the problems started. [Mavers] said to me, 'Your time is nearly up in this band.' I was like, 'What? It's not your band, mate!' I said I’m off, packed my guitar, and got on the bus. I was gutted, two years’ work gone overnight."

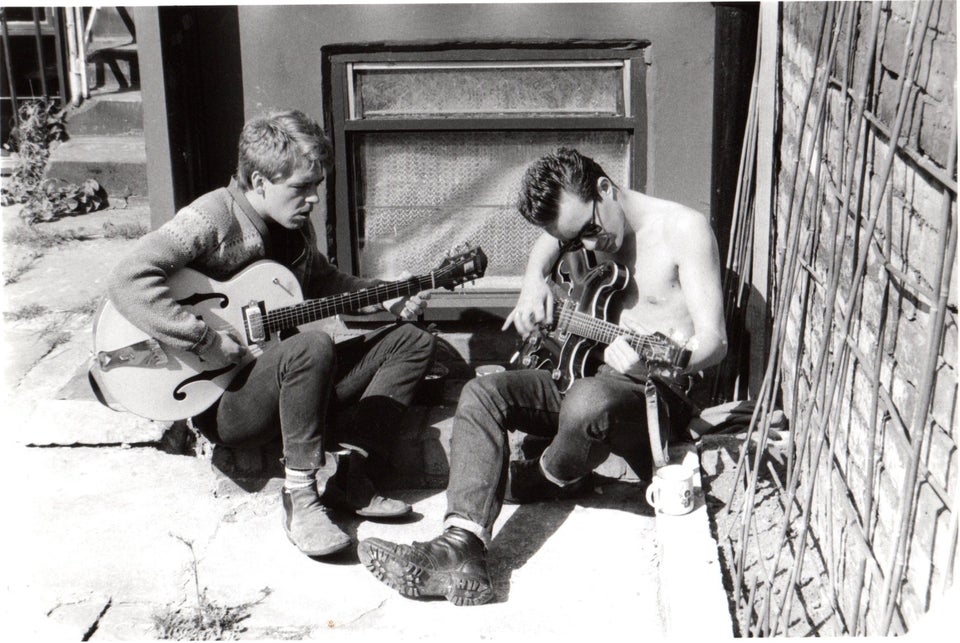

With Badger’s departure, Mavers assumed total creative control. On John Power’s recommendation, guitarist Paul Hemmings was brought in to fill the void. The reassembled La’s retreated to a makeshift rehearsal space in a stable's outbuilding owned by Hemmings’ mother. It was here, amidst the hay and the dust, that the band entered their most fertile period

“Obviously, Mike took all his songs with him,” Hemmings told Northern Soul Magazine. “It was a wonderful time to be in the band, because Lee actually had to write material, and we had to finish it. There was no deliberation. Every single day, there was me, John, and Lee in the stables, working on stuff.”

This stable became the crucible for a string of masterpieces. In a matter of months, the band formulated the backbone of their legacy: ‘Way Out’, ‘Timeless Melody’, and the song that would eventually define them, ‘There She Goes’. It was a period of effortless creation where, as Hemmings put it, "all the stars aligned."

One particular moment in the stable would come to haunt the band for years: the recording of ‘Over’. Captured on a simple ghetto-blaster tape deck, the song was recorded on a sweltering summer afternoon. "The whole thing just flowed," Hemmings recalled. "That’s one of those moments which you could never recapture. You record it the first time, and you never get it again."

Though eventually relegated to the B-side of ‘Timeless Melody’, the raw, ethereal quality of that stable demo became the "holy grail" for Mavers. It set an impossible benchmark for every future studio session; because the band could never quite replicate the "vibe" of that original cassette, the next four years would be spent in a frustrated, million-pound attempt to chase a ghost they had already caught on a cheap tape recorder.

By the end of 1986, the buzz in Liverpool was undeniable. Demo tapes from a session at the Flying Picket rehearsal studio began to circulate through the industry. One tape landed on the desk of a journalist at Underground Magazine, who passed it to Andy McDonald at the fledgling Go! Discs label. While several major labels began circling the group, The La’s chose the independent spirit of Go! Discs, a decision that would set the stage for one of the most tortured recording processes in British music history.

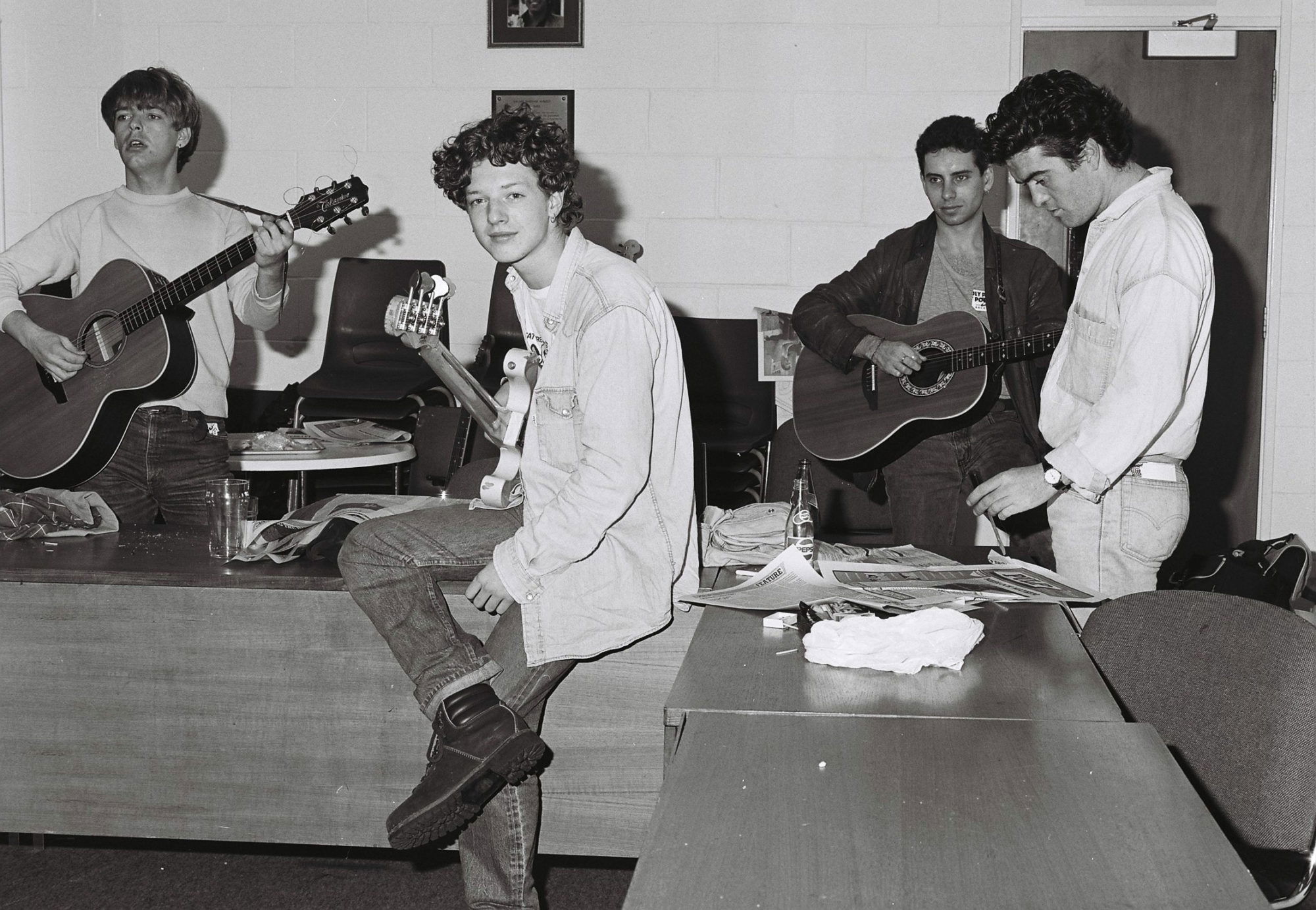

Go! Discs & The First Two Singles- 1987 & 1988

After signing with Go! Discs, the band moved with deceptive speed. In October 1987, they released their debut single, ‘Way Out', a waltzy, frantic desire for escape. Yet, the release established a pattern that would define the next three years: the public heard a hit, but Lee Mavers heard a failure.

‘Way Out’ was eventually recorded by Gavin MacKillop at Townhouse Studios, but only after a disastrous failed session with John Porter at Matrix Studios. Even at this early stage, Mavers was an unintentional pioneer of "lo-fi." He was repelled by the sterile, polished production of the 1980s, seeking instead a warm, organic analogue sound reminiscent of the early mono singles by The Who or The Rolling Stones. He wanted the natural hiss and the hum of the room, the living sound he felt they had already captured on their rough demos. In an era dominated by digital synthesisers, his vision was a language most producers simply couldn't translate.

Written in the Hemmings’ family stable earlier that year, ‘There She Goes’ was built upon a cycling, hypnotic riff and a lyric of romantic yearning for an unattainable girl. With Paul Hemmings adding a complementary guitar line and a subtle nod to the Velvet Underground’s ‘There She Goes Again’, the track was a near-perfect two-and-a-half minutes of indie-jangle bliss.

Despite the song’s breezy exterior, a persistent urban legend suggests it is an ode to heroin, fueled by lines like, "Pulsing through my vein / And I just can't contain / This feelin' that remains." However, the band has consistently dismissed this. Paul Hemmings later clarified in an interview with uDiscover Music: "Lee told me emphatically that it isn’t about heroin... Maver’s songwriting at the time was informed by something more cosmic." Mavers himself described his process in a 1990 Melody Maker interview as almost mediumistic: "The phrasing, the rhythms just come to me... I'm not talking about drugs or anything, but the subconscious is always better than the conscious. There's star material... a light in all of us."

Capturing that "star material" in the studio proved to be an expensive nightmare. It took a year, three different studios, and three producers to finish the single. After an unusable session with Cure producer David M. Allen, they turned to John Leckie at Chipping Norton Studios. Leckie, who would soon produce The Stone Roses' debut, found Mavers’ demands baffling. "Lee was inclined to talk in a kind of Scouse psychobabble," Leckie recalled. "He’d spend half an hour describing the way he’d want the guitar to sound, things like wanting to capture the sound of the tree it was made from. Or he’d decided he didn’t like a particular cable because it was yellow."

As the label watched the band burn through money with little to show for it, Go! Discs took the drastic step of docking the band’s wages. The combination of financial strain and the creative "groundhog day" of playing the same songs hundreds of times led drummer John "Timmo" Timson to quit in late 1987. After a brief cycle of replacements, Chris Sharrock took the stool in mid-1988. Hemmings also departed before the final single version was cut, leaving John "Boo" Byrne to handle the guitar duties.

The version of ‘There She Goes’ the world finally heard was recorded in July 1988 with producer Bob Andrews at Woodcray Studios. By this point, Mavers’s obsession had reached new heights; he reportedly asked engineers to place microphones inside trees and even inside a Steinway piano to catch the internal vibrations of the strings. Most famously, he became convinced that the standard concert pitch was wrong and began tuning his guitar to the low-frequency hum of a nearby refrigerator.

"He was hard to deal with," Andrews admitted. "We were in a residential studio... one day he might not like [a take], then another day he might like it again. But I had to strike while the iron was hot."

The single was finally released in November 1988, a full year after ‘Way Out’. In a final blow to the label and the band’s morale, it failed even to crack the UK Top 50. The masterpiece was out, but the world wasn't listening, yet.

Recording the Debut: 1989-1990

By July 1989, The La’s had already abandoned two attempts to capture their debut record. The first was a self-produced effort at the eight-track Attic studio in Liverpool; the second was a stint at the Pink Museum with producer Jeremy Allom. From the wreckage of the Pink Museum sessions, Go! Discs salvaged a third single: the sweeping, melodic masterpiece ‘Timeless Melody’.

The label pressed the single and serviced it to the press, where Melody Maker promptly named it "Single of the Week." A "song about songs," it used lush harmonies and jangling guitars to explore Mavers’ almost religious devotion to the songwriting process. However, as the release date loomed, Mavers’ dissatisfaction peaked. He felt the recording lacked the "truth" he heard in his head and forced the label to withdraw the single at the eleventh hour.

At this point, perfectionism was curdling into paranoia. The band had been active since 1983, yet by mid-1989, they had only two singles to their name. While Mavers was hailed as a genius in the press, the lack of a finished product suggested a man struggling to live up to his own mythology.

Seeking a breakthrough, Go! Discs owner Andy Macdonald paired the band with Mike Hedges. Known for his work with the early Cure and Siouxsie and the Banshees, Hedges seemed an unlikely fit for a 1960s-obsessed skiffle band. However, he possessed a secret weapon: a vintage 16-channel mixing desk from Abbey Road, the very desk used for John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ and Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon’.

The band, now featuring Mavers, John Power, guitarist Barry Sutton, and drummer Chris Sharrock, retreated to Macdonald’s parents’ house in Devon to record. For a moment, it seemed the ghost had been caught. Mavers was enamoured with the desk's historic warmth. Then, Macdonald made a fatal tactical error. As John Power recalled to Uncut in 2024: “Everyone thought it was great. Lee loved it. Andy was buzzing. Then Andy gave me and Chris £800 each to go on holiday... I think he wanted us out of the way so he could get in Lee’s ear to mix it, but it backfired. Lee got the hump because he didn't come on holiday with us. When we got back, he’d scrapped everything.”

Mavers later claimed he shelved the Hedges sessions to regain control, viewing his bandmates' vacation as a lack of commitment. To the media, however, he offered a more colourful excuse that has since become rock legend: he claimed the Abbey Road desk wasn’t coated in authentic 1960s dust, and therefore could never produce the right sound.

The toll on the band was immense. Barry Sutton, who had attempted to record the same songs on three separate occasions, found Mavers’ direction increasingly impossible to follow. Mavers would demand Sutton play a single part ten different ways, focusing on minute, microscopic changes until Sutton was "deeply paranoid" and his playing began to suffer. "When I was sacked, it came as a relief," Sutton later admitted. Following the Hedges' collapse, both Sutton and Sharrock departed, replaced by Peter “Cammy” Cammell on guitar and Lee’s brother, Neil Mavers, on drums.

In December 1989, six years after their formation, The La’s began a final, desperate attempt at Eden Studios in London with producer Steve Lillywhite. At first, there was mutual respect; Mavers praised Lillywhite’s patience and focus. But the honeymoon was short-lived. "I knew the songs were absolute diamonds," Lillywhite recalled in 2011, "but getting them on tape wasn’t so easy... we’d record six fantastic songs, but if there was one thing wrong on the seventh, he’d be convinced that everything else was terrible, and we’d have to start everything all over again."

The clash was fundamental. Lillywhite used modern techniques like click tracks and piecemeal recording; The La’s wanted a raw, live, organic take. The sessions finally imploded when Mavers reportedly discovered a dossier titled ‘A Producer’s Guide to Dealing with Lee Mavers’, a list of behavioural "dos and don’ts" intended to manage his eccentricities. Incensed, the band walked out, never to return.

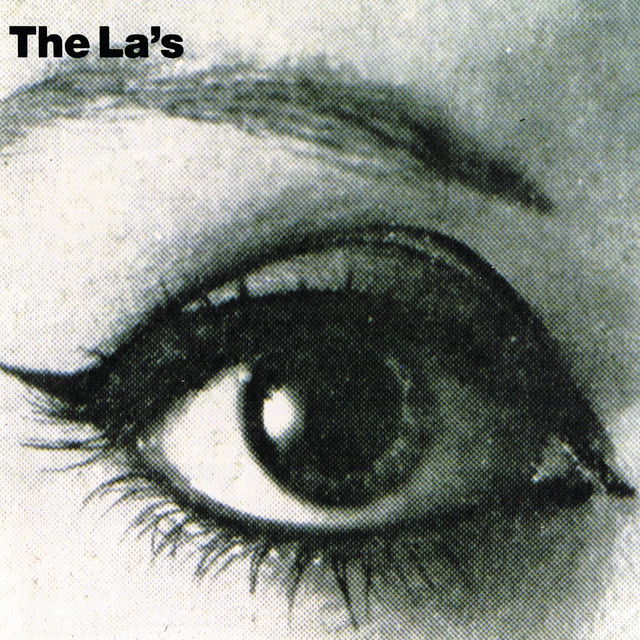

Go! Discs had reached their limit. After three years, eight producers, and a million-pound bill, they ignored the band's protests. They rehired Lillywhite to piece together an album from the existing backing tracks and guide vocals. The result, the self-titled ‘The La’s’, was released in October 1990. The band had no say in the title, the artwork, or the tracklist.

Despite the fractured process, the album was a revelation. It featured the Merseybeat stomp of ‘I.O.U.’, the Beatles-inflected ‘Feelin’’, and the Kinks-inspired ‘Freedom Song’. ‘Son of a Gun’ seemed a perfect mirror for Mavers himself, a man stuck inside his own head. But the centrepiece was the seven-minute epic ‘Looking Glass’. A spacey, ethereal meditation on time and reflection, it saw Mavers reveal a vulnerability he has rarely shown since: "I’m in everybody, everybody’s in me... I see everybody, everybody sees me... in the looking glass, the glass is smashed."

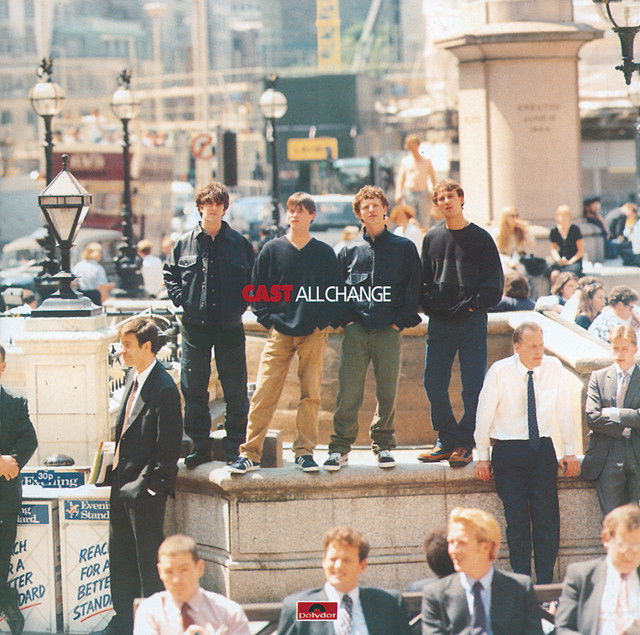

The song’s final line, "The change is cast," would prove prophetic, particularly for John Power, signalling the beginning of the end for the band’s core partnership.

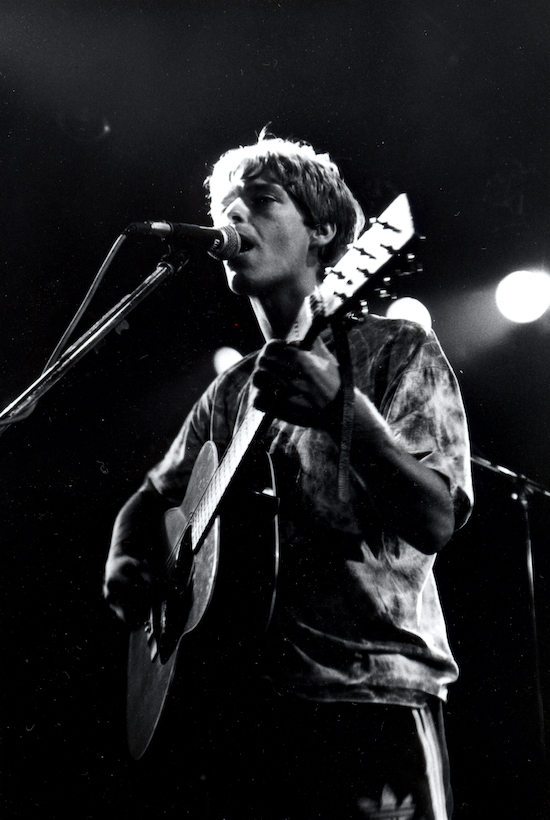

Critics loved the record, and it entered the charts at number 30. A re-worked ‘Timeless Melody’ finally reached the public, but Mavers was already on a warpath. He spent the album’s promotional cycle telling fans not to buy it. "It’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard," he told Melody Maker. "It’s unmusical, it’s out of tune... they took the backing tracks from the first two weeks and used the guide vocals."

Ironically, as Mavers trashed his own creation, the world finally caught up to his genius. A re-release of ‘There She Goes’ in late October 1990 rocketed into the UK Top 20, fueled in part by radio DJs playing it to mark the resignation of Margaret Thatcher. The La's had finally arrived, but the man who had brought them there was already looking for the exit.

All Change 1991- Today

By 1991, the momentum behind The La’s was beginning to stall. The band spent six weeks touring the US, Canada, and Japan, but the atmosphere was far from celebratory. Mavers, weary of journalists asking why he loathed his own masterpiece, deferred most interview duties to John Power. But deeper shifts were happening within the band's power dynamic. While The La’s setlist had remained a static collection of the same 20 songs for five years, Power was growing as a songwriter and began pushing for his own material to be heard.

Much like the earlier power struggle with Mike Badger, Mavers was unwilling to cede the floor. The tension famously boiled over during a soundcheck at the Town & Country Club in London when Mavers refused to sing harmonies on ‘Follow Me Down’, a song written by Power.

"It was guitars down and head-to-head between Lee," Power recalled to Q Magazine in 1997. "It was always, y’know, ‘If you’re not going to sing on my song, I’m not gonna sing on your fking song.’ Just schoolyard shit... I just started shouting into the mike, ‘Sing the fking backing vocals!’ and then we stopped, and it all went off."

Power had been Mavers’ most loyal lieutenant, surviving every failed session and erratic whim, but by December 1991, he had reached his limit. He walked away to form Cast in 1992, alongside Pete Wilkinson from the Liverpool band Shack. The name Cast was a final nod to his past, taken from the very last word ever sung on a La’s record: "The change is cast."

While Mavers retreated, Power soared. By 1994, Cast had secured high-profile support slots with Elvis Costello and Oasis. It was during that tour with Oasis that Polydor’s A&R head, Paul Adam, stunned that the band was still unsigned, moved to secure them. In a moment of poetic symmetry, Cast signed to Polydor on December 13, 1994, three years to the day after Power had left The La’s.

Their debut, ‘All Change’, released in 1995 and produced by former La’s collaborator John Leckie, became a runaway phenomenon. It was the fastest-selling debut in Polydor’s history, yielding four Top 10 and Top 20 hits, including ‘Finetime’, ‘Sandstorm’, ‘Walkaway’, and ‘Alright’, the latter a song Power had originally written during his final days in The La’s. Cast had managed the two things The La’s never could: they conquered the charts and, in 1997, they successfully released a second album, ‘Mother Nature Calls’.

As Cast became Britpop royalty, The La’s became a ghost story. There were fleeting, shambolic sightings, such as a 1994 support slot for Oasis, where a high and rambling lineup (including a returning Cammy and guitarist Lee Garnett) jammed on ‘There She Goes’ repeatedly until the venue cut the power. Rumours of Mavers’ descent into heroin and his continued obsession with authentic 60s dust became the currency of the British music scene

By the turn of the millennium, the "myth of Mavers" had reached its peak, transforming him into the J.D. Salinger of rock. In 2003, fan and author MW Macefield set out to peel back the layers of this reclusive legend for his book, ‘In Search of The La’s: A Secret Liverpool’. After four years of tracking down every former band member and associate, Macefield finally secured what many journalists considered the "Holy Grail": an audience with the man himself.

Expecting to find a tragic, Syd Barrett-style figure lost to "drugs and madness," Macefield instead found a startlingly domestic scenario. He was greeted at a nondescript semi-detached house in the Liverpool suburbs by a warm, sensitive man who answered the door with a baby under his arm. There was no heroin and no mythical 60s dust, just an Everton-supporting father of four living a quiet life. During the visit, Mavers’ eldest son even jumped onto a windowsill to sing along to old La’s demos before his father playfully chased him around the sofa.

Yet, beneath the normality, the obsession remained intact. Mavers was still living off the royalties of ‘There She Goes’, but his creative spirit was as restless as ever. He spent the meeting playing Macefield new material. including a song titled ‘Raindance’ that the author described as one of the best he had ever heard, while steadfastly maintaining that the 1990 album was "shit." Despite the domestic bliss, Mavers was still a man in purgatory, still quietly tinkering with the same songs in his living room, and still waiting for a "right moment" to record them that seemed to exist outside of linear time. The mystery wasn't that Mavers had lost his mind; it was that he had found a peace in the shadows that the music industry simply couldn't understand.

This discovery seemed to spark a brief renaissance. In 2005, Mavers and Power remarkably reunited for a string of shows, including a high-profile set at Glastonbury. While the setlists remained rooted in the 1980s, the inclusion of unreleased tracks like ‘Gimme the Blues’ and ‘Sorry’ hinted at a future that never quite arrived. John Power summed up the situation in 2006: "He’s tinkering with something majestic... whatever he does, whether it’s in this lifetime or the next, it can’t be rushed.

In the years since, the "tinkering" has continued in the shadows. There were brief jams with Pete Doherty in 2008 and a 2011 "stripped back" tour under the pseudonym Lee Rude & The Velcro Underpants. Yet, despite rumors of a Babyshambles-backed second album or sessions with Gary Murphy of The Bandits, nothing has surfaced.

Thirty-five years since the release of ‘The La’s’, a follow-up record remains one of rock's most unlikely miracles. It is a tragedy of perfectionism; the bootlegs and radio sessions, collected on releases like ‘BBC in Session’ and the 2008 deluxe edition, reveal songs like ‘Fishing Net’ and ‘I Am the Key’ that are every bit as breathtaking as the debut. To the world, ‘The La’s’ is a flawless piece of British pop history. To Lee Mavers, it remains a "f**king crap" compromise, a reflection in a glass he’d rather leave smashed.

Impact & Legacy

Many music journalists cite ‘There She Goes’ as the true birth of Britpop, and it is easy to see why. The genre’s hallmark, a backwards-looking musicality paired with chiming, forward-thinking guitars, was essentially an extrapolation of what Mavers had already mastered. The entire seam of acoustic-flecked, electric rock that dominated the 1990s and beyond owes its DNA to The La’s. In the simplest terms, they were the bridge that allowed British pop to continue its lineage from the sixties into the modern era.

The evidence of their influence is everywhere. Oasis’s 2005 Number One single ‘The Importance of Being Idle’ famously pilfers its introduction from The La’s ‘Clean Prophet’, which itself was a nod to The Kinks’ ‘Sunny Afternoon’. Noel Gallagher has never been shy about his devotion; alongside The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and The Stone Roses, The La’s sit at the top of his pantheon. Mere weeks after Oasis released ‘Supersonic’, Gallagher famously declared: “Oasis want to finish what The La’s started.”

In more recent years, Gallagher’s praise has turned into a frustrated fascination with Mavers himself. "When I see him, I say, ‘Hey Lee, when are you going to release your second album?’ And he goes, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’ll do it when I’ve finished the first one... He’s still trying to nail his first set of songs after 27 years. So I’ve come to the conclusion he’s either shit-scared of ruining his legacy or he’s just a lazy c**t.”

But the impact of The La’s stretches far beyond the Gallagher brothers. Their stripped-back sound and melodic sensibility provided the foundation for the rise of Blur, Pulp, Suede, and The Verve. Beyond the nineties, that legacy rippled into the 2000s, inspiring the indie grit of The Libertines and Arctic Monkeys, as well as the blue-collar folk of Jake Bugg. Even modern acts like Fontaines D.C. reflect echoes of the restless energy and timeless songcraft that Mavers pioneered in that Liverpool stable.

At the time, their sound was a defiance of the status quo, an "anti-Madchester" movement that swapped the thumping, pilled-up basements of the M62 for ballsy, melodic prowess. It resonated deeply with the youth of Speke, Seaforth, and Southport. For a working-class, Thatcher-ravaged Merseyside, ‘The La’s’ was an album that transcended its singles; its intricacies and the myths surrounding it still serve as a North Star for Scouse musicians today.

While researching this piece, I found a series of accounts from Liverpudlians reflecting on the band’s shadow. My favourite anecdote perfectly encapsulates the man behind the myth. Joe Maddocks of the band RATS recalled a chance encounter with Mavers outside the Cavern Pub after a Monday night open mic:

“I opened the door after my set to go for a smoke, and it was f**king Lee Mavers outside... He congratulated me, and I sat with him outside, asking about all the interviews and having a proper natter with him. I said, ‘How do you play ‘There She Goes’?’ and he went, ‘Go on, I’ll teach you.’ And there I was, getting a guitar lesson from Lee Mavers on Mathew Street outside the Cavern. People were just walking past thinking it was an old fella because he doesn’t look like a rockstar anymore.”

It is the perfect ending for one of Liverpool’s most gifted songwriters—a man who was never interested in the machinery of fame or the weight of a million-pound debt. He just wanted to be a normal "La."

Thank you ever so much for reading.

For the city of Liverpool: a town of timeless melodies. all those who sail from there, and those who have ever looked through it's looking glass.

Jack x