Through a 'Storm in Heaven'

It's impossible to sum The Verve up in a few crafty sentences. Despite only being a relatively short-lived band, they nearly had as many breakups as albums; their impact on their peers and British music as a whole cannot be understated. Fine-tuning early psychedelic forays on a sequence of highly treasured EPs, and soon became firm darlings of the independent and mainstream pop press as well as an influence on their peers – Oasis, in particular, were champions.

The band's career is marked by major highs and extreme internal lows, but it's unfair just to examine the extremely good and the extremely bad. The Verve are so much more than the big anthems and the internal fractures.

Gravity Grave: Formation: 1990 to 1992

The Verve formed in Wigan in 1990, originally under the name Verve. The members met at Winstanley Sixth Form College, where Richard Ashcroft was introduced to the rest of the group by Liam Begley. The original lineup of Richard Ashcroft (vocals), Nick McCabe (guitar), Simon Jones (bass), and Peter Salisbury (drums) quickly developed a strong chemistry, bonding over their shared love of psychedelic and alternative music.

Their first gig took place at a friend’s birthday party at the Honeysuckle Inn in Wigan on 15 August 1990. At that point, they had only a handful of songs but relied heavily on long, hypnotic jam sessions to shape their material. Much of the band’s early sound emerged from these improvisations, with McCabe’s swirling, reverb-heavy guitar textures providing a distinctive backbone for Ashcroft’s commanding and introspective vocals. Even in these early performances, the band began to attract attention for their ability to captivate audiences with their musical intensity and experimental approach.

Throughout 1991, Verve built a solid reputation on the local gig circuit, performing in small clubs and pubs across the North West of England. Their live shows were immersive and often unpredictable, with extended instrumental passages that blurred the line between shoegaze, psychedelia, and dreamlike rock. As word spread, the band’s reputation grew rapidly. By mid-1991, they were drawing the attention of music journalists and record labels alike.

A pivotal moment came with their appearance at Manchester’s famed Boardwalk club, a venue central to the city’s vibrant indie scene. Their performance there was a revelation; by two songs into the set, Ashcroft had already won the crowd over. It was clear that Verve were something different: a band whose sound was both otherworldly and deeply emotional. Their ability to create vast soundscapes with minimal reliance on traditional song structures set them apart from their peers in the early ’90s alternative scene.

Later that year, the band signed with Hut Records, a subsidiary of Virgin Records that specialised in up-and-coming alternative acts. The signing marked a turning point. Verve now had the support and resources to bring their vision to a wider audience. They entered the studio with producer Paul Schroeder to record their debut single, 'All in the Mind', which was released in March 1992. The single reached number one on the UK Independent Singles Chart and established Verve as one of the most exciting new acts in British music.

The band followed it up with 'She’s a Superstar' in June 1992, a sprawling, psychedelic track that captured their live energy and sonic ambition. It once again topped the indie chart and introduced more listeners to their transcendent sound. Verve spent much of 1992 touring relentlessly, performing alongside acts such as Ride and Spiritualized. Two bands that shared the outlook on music that Verve had at that time.

Their third single, 'Gravity Grave', released in October 1992, pushed their musical boundaries even further. Clocking in at over eight minutes, it showcased their penchant for epic, slow-burning arrangements. The accompanying video, filmed in the rolling countryside of Northern England, reflected the band’s connection to nature and the open, expansive qualities of their music. The single was a critical success and has since become emblematic of the band’s early period.

In December 1992, Verve released the 'Verve EP', a compilation of their early work that captured the essence of their formative years. The EP blended shimmering guitar soundscapes with Ashcroft’s poetic lyricism and established the group as one of the most adventurous new bands on the British scene. By this point, Verve had evolved from local cult heroes into one of the UK’s most promising alternative rock acts, admired for their emotional intensity, instrumental depth, and willingness to defy convention.

By the end of 1992, the band’s momentum was undeniable. Their singles had topped the indie charts, their live shows were drawing packed audiences, and the British press had begun to take serious notice of their visionary approach. As 1993 approached, Verve entered Sawmills Studio in Cornwall with producer John Leckie to begin work on what would become their debut album.

Let Go and 'Slide Away': A Storm in Heaven: 1993 to 1994

By 1993, The Verve had established themselves as one of the most exciting bands in Britain, and on one of their many support slots had bagged themselves some famous fans, including John Leckie. Leckie had been the producer on the legendary Stone Roses debut album and approached the band about producing them.

Leckie had first seen the band supporting Whirlpool in London and was so impressed that he began to hunt for gig posters to see when they were performing again. Up to that point, he was known for achieving the best sound for newer bands, though he thought that there would be some difficulty in translating their sound onto a recording. Leckie was amazed by their "dynamics, how devastatingly loud they could be, and how quiet and sensitive they would be. At points you could hear a pin drop — and then it would just explode."

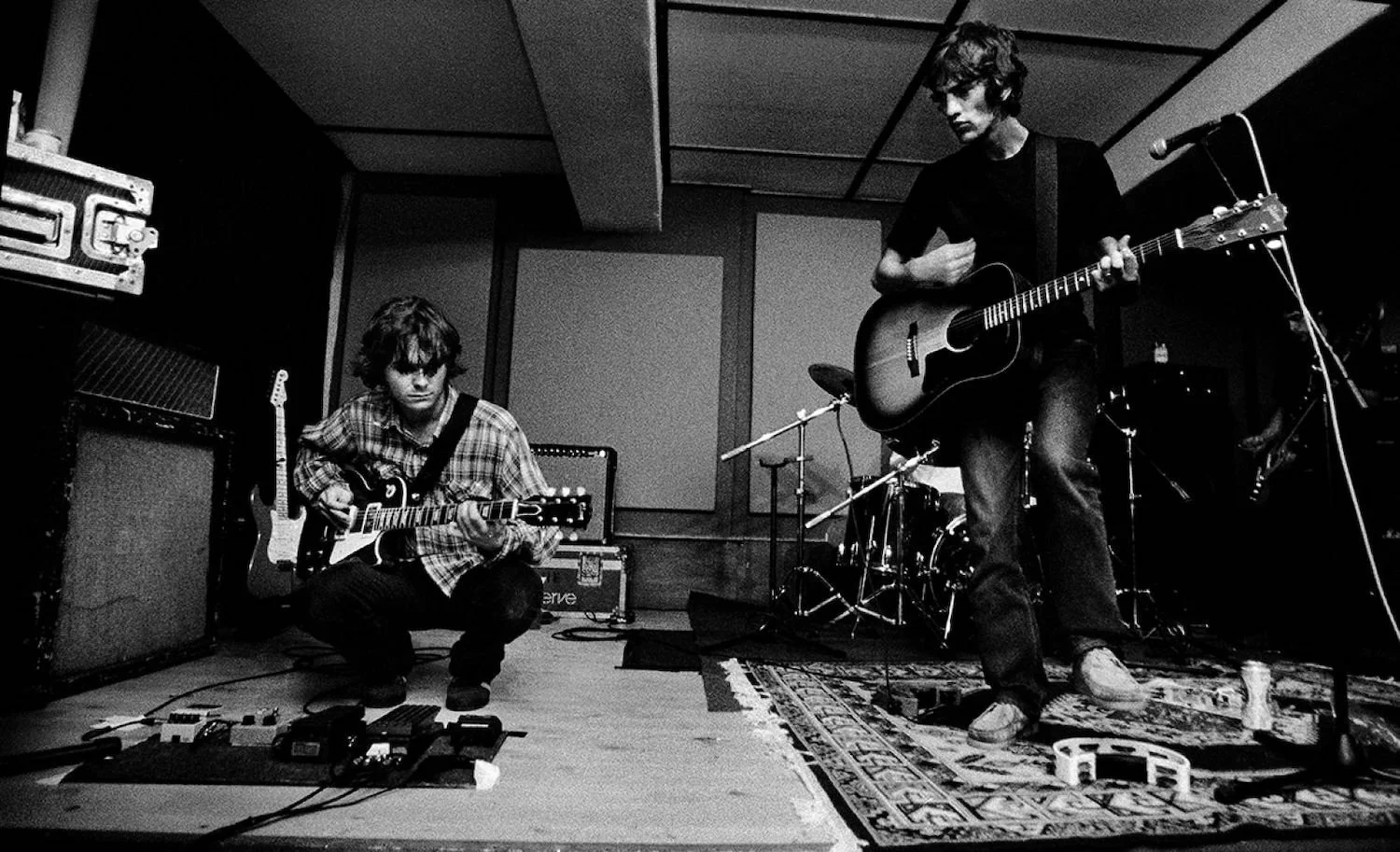

Despite only having three songs, 'Slide Away', 'Already There', and 'The Sun, the Sea' written at this point, the band and Leckie headed to Sawmills Studios in Cornwall, set on making a record. The sessions started in December 1992 and went into January 1993, with a break for Christmas. As the studio was in an isolated area, they could only reach it by boat or by walking down a railway track when the tide was out. If their gear had not arrived by the same boat, they would be forced to wait for 12 hours for the tide to rescind. Its location meant that the band members would not be distracted.

The location and circumstances really worked for the band; they did not feel pressured to come up with something special from the very outset. Instead, they gave themselves time to find ideas and figure things out. Eight of the album's final songs came about through improvisational jamming. This working method was hit-and-miss productivity-wise, as five days could pass without anything substantial, while two songs might evolve in a brief period of time. Ashcroft compared it to looking at an empty canvas: "... you don't know what you're going to paint, but you know it's going to be great."

Leckie focused on getting the right atmosphere instead of working with discipline, a method that McCabe preferred, having previously disliked their prior sessions for taking too much time setting up the drums and getting a particular bass sound. Leckie aimed to capture the band's live spirit when he saw them live. John Cornfield did engineering and programming throughout the sessions. Members of Verve did not like contemporary albums for being overproduced and too clean, wanting a "dirty" sound instead for their debut.

The lead single, ‘Blue’, released in May 1993, distilled their vast sound into a hypnotic, melodic track that shimmered with melancholy and beauty. Its video, directed by Jake Scott, mirrored the band’s connection to nature, depicting them against dreamlike landscapes bathed in hazy light. ‘Blue’ offered a gateway into The Verve’s sound.

The song started with McCabe playing one guitar part, reversing it, and playing over that. It's a real statement of intent, though, with some of Ashcroft's most direct and powerful lyrics. Written and recorded at 6 am on the day the band were due to deliver the master tapes to an increasingly agitated Virgin Records.

'Slide Away', the second single, is arguably the album's best work, though, the second song the band ever composed. Beginning akin to the work of Ride, as the song progresses, McCabe displays varied playing styles, from riffs akin to the work of Led Zeppelin to a wall of sound. The track was a live favourite at shows, which translated well to a recording, showing the soft and quiet to loud noise dynamic that initially piqued Leckie's interest in the band.

Ryan Leas of Stereogum said of the song For the last 50 seconds of the song, Ashcroft's vocal wrestles with the increasing sound of the guitar work as it envelops him, but in the end he takes the song's advice and lets the currents carry him away."

It's one of my favourite songs that the band has ever recorded.

The final single, ‘Butterfly’, appeared later in 1993 and revealed a quieter, more introspective side of the band. Built on delicate textures and introspective lyrics, it carried an emotional weight that hinted at the inner conflicts that would later define the group. It wasn’t a chart hit, but it reinforced The Verve’s commitment to artistry over commercialism. Its name stems from Ashcroft being interested in chaos theory and the concept that a butterfly fluttering its own wings in one area can have consequences in a different area. McCabe said it has its origins in him and Ashcroft playing around with a Steely Dan loop, where he was "making bonker noises, hitting my guitar, stoned out of me mind as well..."

When ‘A Storm in Heaven’ was released in June 1993, it immediately stood apart from anything else emerging from the UK scene. At a time when Britpop was beginning to take shape, The Verve’s debut rejected conventional pop structures in favour of atmosphere, texture, and feeling. Leckie had managed to bottle the magic.

As Nick Southall wrote in Stylus, “Verve went into the studio with half a dozen riffs, half a dozen half-baked lyrics and a thousand ideas of ways to reach the sky. Leckie managed to seize the controls and apply the necessary degree of restraint and maturity, guiding the band back down to earth when they threatened to fly too close to the sun.”

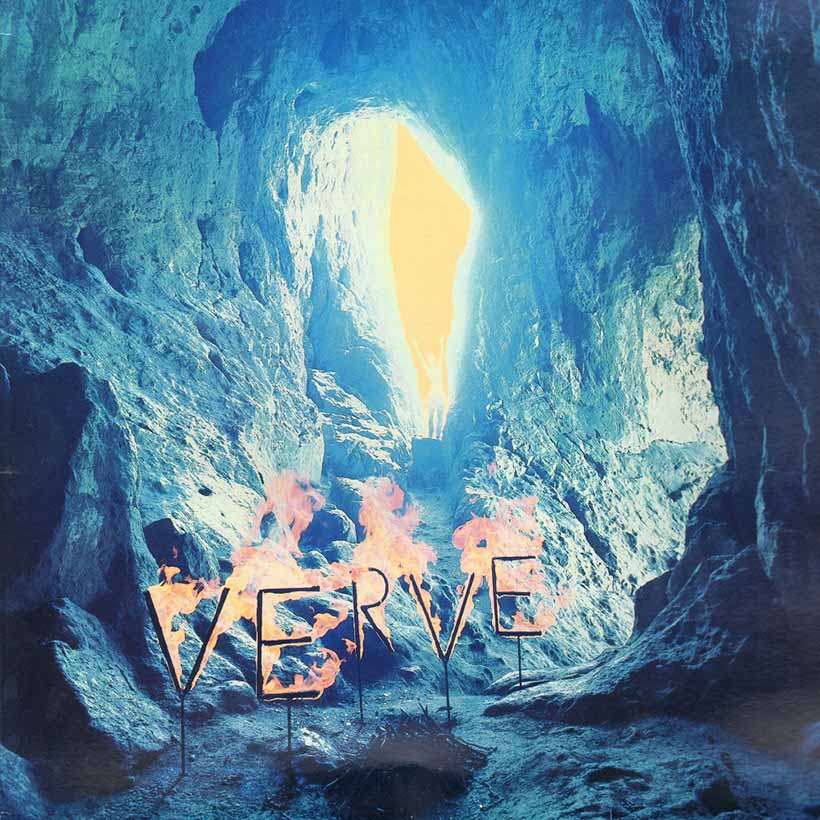

One of the biggest talking points about this album is its cover art.

Designed by Brian Cannon of Microdot and photographed by Michael Spencer Jones, the cover was shot at Thor’s Cave in Staffordshire — a vast natural cavern carved into a limestone hill, whose entrance rises nearly ten metres high and seven and a half metres wide. The band were fascinated by the cave’s mythology, which included Palaeolithic burial sites and local legends about it being the resting place of the wife of an 8th-century martyr.

As with their earlier releases, The Verve wanted their name to be part of the photograph itself rather than added later. Spencer Jones hired a friend to weld enormous metal letters spelling “VERVE”, which were then dragged up the hillside to the cave’s mouth. Originally, Jones planned to shoot the cave from outside, but while walking with his girlfriend, he realised the best perspective was from within the cave, looking outward into the valley. Cannon suggested setting the letters alight to contrast with the cave’s eerie blue illumination, producing a striking colour composition that gave the scene a surreal, elemental power.

Spencer Jones later described the final image as having an almost womb-like quality, a metaphor for creation and rebirth. To enhance that theme, he added a shadowy human figure emerging from the cave’s depths, symbolising the cycle of life. The process wasn’t without its difficulties: each time they tried to ignite the wicks atop the metal letters, the flames on the “V” would die before they reached the “E”. The result, however, was one of the most iconic and symbolically rich album covers of the 1990s, a visual representation of The Verve’s search for light and meaning within darkness.

While ‘A Storm in Heaven’ reached only number 27 on the UK Albums Chart, it remains one of the most striking debut albums of its decade — an atmospheric and spiritual statement of intent. It represented The Verve at their most pure and searching, unbound by expectation or compromise. The album’s sound and imagery — from the glowing letters in Thor’s Cave to the swirling guitars and celestial production — captured a band not just making music, but conjuring a vision.

By the end of 1993, The Verve had emerged as one of Britain’s most intriguing and influential young acts. Though still on the fringe of mainstream recognition, their combination of sonic beauty, emotional depth, and fearless experimentation marked them out as a band destined for greatness.

With ‘A Storm in Heaven’ completed in the spring of 1993, The Verve were finally ready to bring their visionary sound to a wider audience. The album’s release in June marked not just a creative milestone but the beginning of an exhausting and transformative period of touring that would carry them across the UK, Europe, and the United States.

The band’s live shows were unlike anything else in British music at the time. What had begun as long, improvised jams in Wigan pubs had evolved into transcendent, unpredictable performances. Each night, songs stretched far beyond their recorded versions, moments of quiet introspection would explode into towering walls of sound, McCabe’s guitar shimmering and bending as Ashcroft prowled the stage like a man possessed

Their UK shows drew critical acclaim, with journalists hailing them as one of the most exciting and uncompromising new live acts of the decade. Audiences were drawn into their world, a mixture of beauty, chaos, and raw emotion. As ‘Blue’, ‘Slide Away’, and ‘Butterfly’ began to circulate, The Verve’s sound spread through the indie press and college radio, building a reputation that extended well beyond Britain’s borders.

The Verve’s growing live reputation reached a new height with their Glastonbury Festival appearance in June 1993. Performing on the NME Stage, they delivered a set that is now considered one of the most atmospheric and memorable of the festival’s early ’90s era. Shrouded in fog and drenched in deep blue light, the band conjured an otherworldly atmosphere as they played tracks like ‘Slide Away’, ‘Blue’, and ‘Already There’. Ashcroft’s performance was magnetic, and McCabe’s shimmering guitar created a sound that seemed to hang in the Somerset air. For many fans and journalists present, it was the moment The Verve became something more than a cult act; they had arrived as a major creative force.

Late in 1993, they embarked on their first major European dates before heading to the United States. The American tour was intense and at times chaotic. The band’s otherworldly music was finding an audience among fans of the expanding alternative rock movement, but life on the road was gruelling. The combination of heavy touring, exhaustion, and the band’s well-documented indulgence in psychedelics led to erratic behaviour and mounting internal strain.

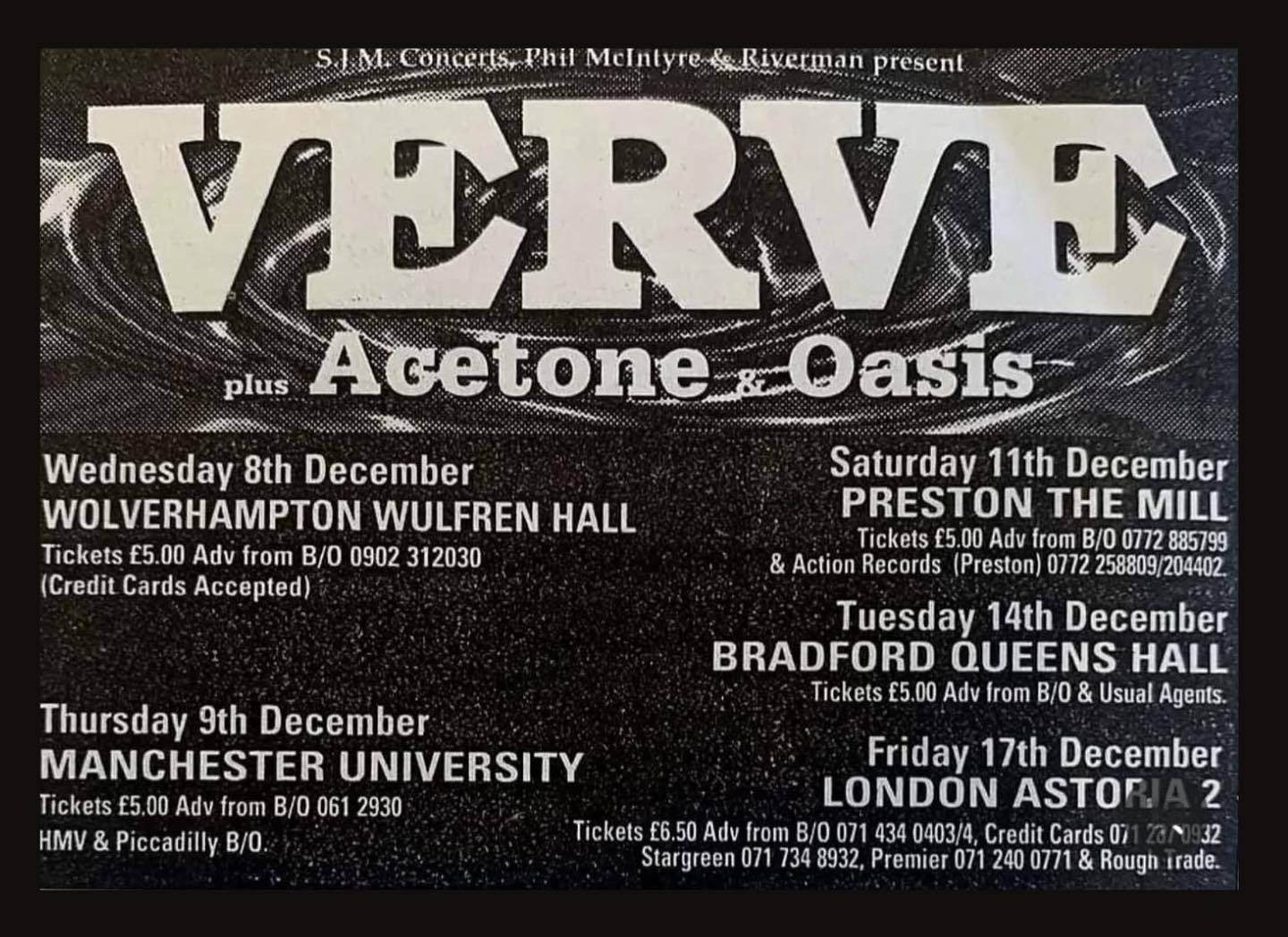

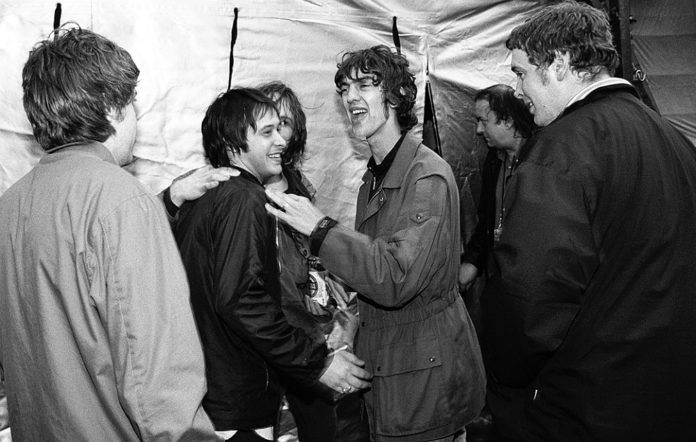

Amid this whirlwind, The Verve crossed paths with another young Northern band on the rise, Oasis.

The two groups met while gigging on the same circuit, immediately recognising a kindred spirit in one another. Ashcroft and the Gallagher brothers struck up a friendship based on mutual respect and a shared belief in music as something transcendent. Both bands were uncompromising in their vision, raw, emotional, and utterly convinced of their own destiny. Their encounters in those early days helped to define the new wave of British music that was about to explode.

In 1994, the band released the album 'No Come Down', a compilation of B-sides plus a live version of 'Gravity Grave' performed at Glastonbury Festival in 1993. It was the band's first release under the name 'The Verve', following legal difficulties with jazz label Verve Records

As 1994 unfolded, The Verve’s touring commitments continued across the UK and the US. However, the relentless pace, lack of stability, and substance-fuelled chaos began to fracture the band’s unity. Incidents such as Ashcroft being hospitalised for dehydration after a massive session of drinking, and Salisbury was arrested for destroying a hotel room in Kansas in a drug-fuelled delirium. Ashcroft later recalled: "At the start, it was an adventure, but America nearly killed us.

By the end of 1994, The Verve had reached a crossroads. They had toured relentlessly for over a year and a half, from the ethereal heights of ‘A Storm in Heaven’ to the exhaustion and volatility that followed. Their music had evolved; the shimmering psychedelia of their debut was giving way to something darker, more direct, and emotionally charged.

When they finally returned home, it was clear that change was inevitable. The Verve had seen the edge of transcendence and the brink of collapse, and both would feed directly into their next record.

This is the tale of a 'Northern Soul': 1995 to 1996

The Verve's physical and mental turmoil continued into the chaotic recording sessions of their second album, 1995’s ‘A Northern Soul’, produced by Owen Morris. The band departed from the lush, experimental psychedelia of ‘A Storm in Heaven’ and moved toward a more visceral, emotionally charged sound. Ashcroft’s vocals now sat firmly at the centre, raw and unguarded. McCabe’s guitar still shimmered with texture, but now carried a darker, heavier edge. It was a shift from transcendence to confrontation; the sound of a band wrestling with their own intensity.

Since the recording of their debut album, Ashcroft had some life-changing experiences that would fuel his songwriting. Towards the end of 1994, Ashcroft and his girlfriend, Sarah Carpenter, ended their six-year relationship when the latter became infatuated with one of the band's roadies, Andy Burke, who was also one of Ashcroft's best friends. As Ashcroft was dealing with this, Jones was also going through mental struggles. The latter found it difficult to acclimatise at home in Wigan after Lollapalooza and the US in general. McCabe was also breaking up with his pregnant girlfriend, Monica; he was growing weary of others around him. Ashcroft fled to London and, subsequently, the countryside without informing anyone. Ashcroft attempted to reconcile with her in London over a period of three months. For two of those three, he was mentally and physically exhausted. When he reconvened with the rest of the band, they were performing the music that he felt conveyed the emotions he was experiencing, allowing the two aspects to go together with relative ease.

Ashcroft stayed with the band's co-manager, John Best, who was dating Lush frontwoman Miki Berenyi, for a period of six to eight weeks. Best had a Portastudio in his front room that Berenyi used for making songs, which Ashcroft used when borrowing her acoustic guitar to write for himself.

When the band wanted a different producer for their second album, Noel Gallagher of Oasis proposed Owen Morris, who had co-produced 'Definitely Maybe'. Morris himself shared a similar perspective on the rock and roll lifestyle as the Verve. Ashcroft said they went with him as he was around their age and equally as intense as the rest of the band in "everything we do, lifestyle, music, everything ..." As the members wanted to avoid repeating mistakes that they had made on 'A Storm in Heaven', they set about writing before entering a studio. The band holed up in their former rehearsal space in Wigan, which Ashcroft dubbed a "black hole, a claustrophobic pit."

The space was located in a dark industrial warehouse, which they felt was inspirational to the point that Ashcroft and McCabe put aside their personal issues. The members drove around during the night on occasion, seeking further inspiration. Ashcroft learned of a tale from Keith Richards where he talked about the Rolling Stones being mocked by Dean Martin, which he connected to and used as an influence: "That's what happened to us ... we just thought, 'Fuck you all, we're gonna delve into our black hole in Wigan and make the greatest music you've heard in your life.'"Morris, whose visibility as a producer increased after Definitely Maybe, visited the band during one of their rehearsals, feeling enthusiastic about what he was hearing. It was a fruitful period, with them having two albums' worth of songs in time for recording, contrasting with creating the bulk of A Storm in Heaven as they were recording it.

The initial idea for the recording sessions was to take the recording gear to their rehearsal room, as they were the most productive there, and it had the right atmosphere. When they realised that it was impractical to use it for recording, they decided on Loco Studios in Wales.

Philip Wilding, author of The Verve: Bitter Sweet (1998), wrote that the sessions for their second album became mythologised as a combination of "lurid stories and gruesome hearsay echoing in stories of drug-fuelled jam sessions that became extensive recording sessions and bouts of reckless violence."

John Best described the situation as lunatics running an asylum. Author Sean Egan, in his book The Verve: Star Sail (1998), said various tales have since come out about the sessions, including: Ashcroft allegedly totalling a hired car by driving it on the studio's lawn; the band often playing a single song for hours at a time; Ashcroft disappearing for five days; and the band debating whether to destroy a tape machine, which was valued at £100,000, so that they could get a sound to end the album on.

Morris was exhausted from the sessions, as the band, going as far as to say they did not need a producer, as they would "do [a] producer's head in. According to Jones, Morris exclaimed that he would never work with the Verve again, almost quitting towards the end of the sessions. Ashcroft commended Morris for involving himself to the degree that he saw him akin to a member of the band. Adding that they sought a producer that was "extreme. Owen brought his personality to the record. [...] He admitted he nearly had a nervous breakdown, and I think that's a commendable performance."He summarised the process as four challenging months that were "insane. In great ways and terrible ways. In ways that only good music and bad drugs, and mixed emotions can make

‘This Is Music’ was released as the lead single from ‘A Northern Soul’ in May 1995. The track was an assertive statement of purpose, blending driving rhythms, swirling McCabe guitars, and Ashcroft’s urgent, impassioned vocals. Written in the aftermath of Ashcroft’s personal upheaval, it conveyed both defiance and introspection, capturing the tension and intensity that had defined the Loco Studios sessions. The song’s layered guitars and pulsing bass created a sense of forward motion, almost like a rallying cry for a band asserting themselves against chaos and expectation. Critics praised its raw energy and sonic ambition, and it quickly became a live favourite.

A month later, ‘On Your Own’ was released as the album’s second single, showcasing a more reflective and melancholic side of the band. Where ‘This Is Music’ was forceful and outward-looking, ‘On Your Own’ was intimate and inward-looking, a quiet, elegiac meditation on isolation and emotional vulnerability. Ashcroft’s vocals were more restrained, almost conversational, while McCabe’s guitar arpeggios shimmered delicately over the steady pulse of Jones and Salisbury’s rhythm section. The track revealed the depth and maturity of the band’s songwriting, offering listeners a window into the personal and emotional states that had driven the album’s creation. Critics lauded the song for its bittersweet beauty and lyrical honesty, and it became emblematic of the reflective, almost confessional mood running through ‘A Northern Soul’.

The album reached the UK Top 20 upon its release in July

Initial promotion consisted of a one-off show in Newcastle, a supporting slot for Oasis in Scotland, a performance at Phoenix Festival, and a US tour. The strained relationships between the band members came to a head when they performed at T in the Park in August 1995.

Ashcroft broke up the band a few weeks later, just before the release of the third single ‘History’, which reached No. 24 in September. The song begins with a string intro that is very similar to the intro of 'Mind Games' by John Lennon. This was the first song by the band to feature strings. The opening lyrics of the song are based on the first two stanzas of William Blake's poem, London. The song is quite melancholic, with Melody Maker describing it as "an epic, windswept symphony of strings, flailing vocals and staggeringly bitter sentiments". It has been claimed that the song was written about Richard Ashcroft's split with his girlfriend, although Ashcroft denied this.

Ashcroft later stated about him leaving the band: "I knew that I had to do it earlier on, but I just wouldn't face it. Once you're not happy with anything, there's no point living in it, is there? But my addiction to playing and writing and being in this band was so great that I wouldn't do anything about it. It felt awful because it could have been the greatest time of our lives, with "History" doing well, but I still think I can look myself in the mirror in 30 years and say, 'Yeah man, you did the right thing.' The others had been through the same thing. It was a mixture of sadness and regret, and relief that we would have some time away."

The band bowed out at what had been their peak. 'History' was an epic moment, albeit a fleeting one. However, they'd shown the music-buying public just how good they were.

It's a 'Bittersweet Symphony': 1995 to 1998

After the sessions for ‘A Northern Soul’, Ashcroft left the band, and The Verve officially broke up. When the news became public, the press struggled to reach him he was camping in Cornwall. Unlike his former bandmates, Ashcroft showed little concern about his future. As The Verve’s principal songwriter, he was seen by their label, Hut, as a strong solo prospect. His reputation for delivering memorable soundbites made him a media favourite, even among those indifferent to the band, giving the label a ready-made platform for launching his solo career.

In the wake of the breakup, Ashcroft drifted between hotels, friends’ houses, and his mother’s home. Co-manager Jane Savage recalled that he appeared at the offices of their PR firm, Savage & Best, announcing plans to work with new musicians and even form a six-piece band.

A few weeks later, Ashcroft reconnected with bassist Simon Jones and drummer Peter Salisbury. He and his wife, Kate Radley, relocated to Bath, Somerset, renting a flat near her parents’ home. There, Ashcroft began writing again while Jones, Salisbury, and new recruit Simon Tong waited in London for him and his new songs.

Tong, an old friend from Winstanley College, was brought in to play keyboards and support Ashcroft’s guitar parts. Years earlier, Tong had been the one to teach both Ashcroft and Jones their first guitar chords.

During this time, Ashcroft recorded nine demos, including early versions of ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’, ‘The Drugs Don’t Work’, ‘Sonnet’, and ‘Space and Time’. He insisted, however, that without Nick McCabe, they were not truly The Verve. He declared that the studio sessions would become a solo record or a project under a new name.

By September 1995, co-manager John Best reported that Ashcroft already had enough songs to begin recording. Sessions were held at Real World Studios in Bath with producer John Leckie, where they created 32 demo recordings. None were completed, as Leckie noted, because the musicians were “too familiar with one another.” Dissatisfied, Ashcroft refused Hut permission to release the material.

Without McCabe, the band’s sonic architect, Ashcroft had to rebuild his musical approach. He began crafting rhythms by clapping out tempos or experimenting on the piano, constructing songs from the ground up. In 1996, he spent time with Oasis, studying how they functioned as a unit. When he opened solo for them at Madison Square Garden, the audience’s reaction convinced him that he wasn’t suited to performing alone; he needed a band.

In May 1996, Ashcroft, Jones, Salisbury, and Tong entered Rockfield Studios in Wales with producer Owen Morris, who had produced ‘A Northern Soul’. The chemistry that had once driven them, however, was gone. What was meant to be a week-long session ended after only two days. When Best asked who might replace their missing guitarist, the group agreed they needed someone exceptional. Names like John Squire of The Stone Roses and Bernard Butler, formerly of Suede, came up. Both were available, and Butler eventually joined the sessions for a short period after meeting Ashcroft at Best’s suggestion.

By mid-1996, the band was recording at Olympic Studios in London with producer Martin “Youth” Glover. Youth insisted on disciplined hours, arriving by 10 a.m., working through the day, and finishing in the evening. He encouraged Ashcroft to move away from Stone Roses-style influences and pursue a more classic rock sound. One track he pushed Ashcroft to keep developing, initially titled ‘Stones Song’, evolved into ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’.

Ashcroft welcomed Youth’s structure, which helped temper his hedonistic habits, though he gradually began arriving later each day. Throughout the sessions, tapes were labelled “Richard Ashcroft,” but Youth would write “The Verve” on the boards, something Ashcroft kept correcting. He had no intention of reviving the band’s name, feeling it would be fraudulent, “like The Doors without Jim Morrison or The Clash without Mick Jones.” Youth noted that Ashcroft wanted to preserve the band’s legacy rather than exploit it. Even without a name for the new project, Ashcroft had already chosen a potential album title: ‘Urban Hymns’.

Despite progress, Ashcroft sensed something was missing. Youth’s structured approach, while productive, lacked the free-flowing creativity of The Verve’s earlier jam sessions. Ashcroft found himself thinking often about McCabe and his musical brilliance.

In late 1996, strings were recorded for ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’. Working with arranger Wil Malone, Ashcroft developed two separate orchestrations built around a looping sample of ‘The Last Time’ by The Rolling Stones. His goal was a cinematic arrangement, a modern echo of Ennio Morricone’s work.

After Christmas, Youth departed, and engineer Chris Potter took over as producer. By that point, Virgin Records had already spent £2 million on the project. Though Potter lacked major production credits, his hands-off approach suited Ashcroft, who didn’t want an overbearing producer.

Still, the music felt incomplete. Without McCabe, the chemistry of earlier sessions was absent. In early January 1997, Ashcroft finally reached out to him. After several failed attempts to contact him, he tracked McCabe down through a friend. Ashcroft reportedly told him, “I’ll quit music if you don’t come back.” McCabe later admitted that, although he initially wanted to tell Ashcroft to go away, he was glad he’d called.

McCabe’s return caused some unease at Virgin, who feared he’d turn the record into something experimental or “krautrock-like.” Yet his presence revitalised the sessions. Tong remained on board, providing guitar and keyboard parts. By then, around 15 tracks had been recorded, and McCabe’s additions complemented rather than replaced the existing material. He noted that several songs had been loop-based and overly rigid, so he and Potter brought in a Pro Tools rig to encourage improvisation. McCabe re-recorded guitar parts for all of the album’s singles, breathing new life into the music.

The new lineup reignited momentum. After an internet leak, they re-recorded two ‘Northern Soul’ tracks: ‘The Rolling People’ and ‘Come On’. A ten-day session in May 1997 produced ‘Weeping Willow’, ‘Catching the Butterfly’, ‘Three Steps’, and ‘The Longest Day’.

As mixing drew to a close, ‘Neon Wilderness’ emerged spontaneously when McCabe began experimenting with a loop. The song was written and recorded in just 11 hours, wrapping up at 7 a.m. on their final studio day. In total, the band spent nine months recording and mixing what would become one of the defining albums of the 1990s.

The bands' return had not been announced until May of 1997; by then, the British music-buying public and critics had diverted their eyes to Radiohead, who were releasing 'Ok Computer' and Stereophonics, who had just released their debut album. During the time the Verve were absent, Britpop started to decline in popularity as electronica and its associated acts, such as the Chemical Brothers, the Prodigy, and Underworld, grew in prominence.

The Verve had a plan, though; the orchestral epic 'Bittersweet Symphony' was set to be the lead single. However, the Andrew Oldham sample needed to be cleared. Yet the band were hopeful, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had heard the song and were fans of it. However, despite the sample being from a Rolling Stones track, it was owned by businessman Allen Klein and his record company ABKCO Records, who subsequently denied the clearance. Klein said he did not like sampling as a concept and would not allow it for a Rolling Stones song.

This led to a lawsuit, and Klein's terms for agreement were 50% of all royalties, the standard percentage for samples, which the Verve agreed to. ABKCO contacted them again shortly before the song's release, demanding 100%, though this bid was too late to have an effect. The songwriting credits on the song were changed to Jagger-Richards. Ashcroft lost everything. In 2019, a surprising turn of events occurred. Jagger and Richards returned the rights of 'Bittersweet Symphony' to Ashcroft, acknowledging that the song was his creation.

The song was released as a single in June 1997, and it reached Number Two on the UK Singles Chart.

Despite being over the traditional length of a pop song, it received plenty of play in the UK, and its video is one of the most iconic of the 1990s. Shot on Hoxton Street in North London over several days due to inclement weather, as the recording sessions for the album were concluding, has Ashcroft walking down a pavement as he mimes the song's lyrics. Ashcroft came into contact with other pedestrians along the way, appearing oblivious as he bumped into them or knocked them to the floor. It was directed by Walter Stern, who previously directed the videos for 'Breathe' (1996) and 'Firestarter' (1996), both by the Prodigy. The video served as a tribute to the video for 'Unfinished Sympathy' (1991) by Massive Attack; their vocalist, Shara Nelson, is seen in a street in Los Angeles, California, also disregarding people who were close by.

The circumstances for the song had not been ideal, and Ashcroft had lost his biggest hit, in situations outside of his control. However, The Verve were back, and now they had a hit. The song has become the band's known song and one of the defining songs of the 1990s.

If the first single had done well, the second single eclipsed it. 'The Drugs Don't Work' gave The Verve a number one single. It debuted at Number One and seemed to sum up the mood of a nation. Released the day after the death of Princess Dianna.

Lead singer Richard Ashcroft wrote the song in early 1995. He briefly mentioned it in an interview at the time, relating it to his drug usage: "There's a new track I've just written ... It goes 'the drugs don't work, they just make me worse, and I know I'll see your face again'. That's how I'm feeling at the moment. They make me worse, man. But I still take 'em. Out of boredom and frustration, you turn to something else to escape."Over the years, people have speculated that the song is about someone close to Ashcroft who was dying; however, Ashcroft has been reluctant to give further details as he feels that people have their own views, and if he underlined his own interpretation, that would be "killing it for people"

The song's melancholic nature was unlike anything the band had ever done before. It really pulls on the heartstrings, and it hits all of the right peaks and troughs. It's full of romance, heartache ache and cinematic precision. Some could say that this is the song that killed Britpop; it brought the death of the party. The end credits on three and a half years of hedonism.

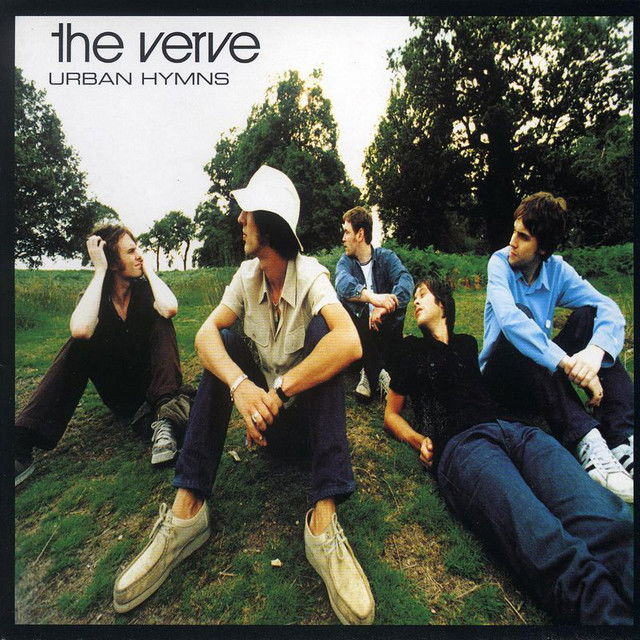

'Urban Hymns' reached number one on the UK Albums Chart that month, knocking off Oasis' highly anticipated album 'Be Here Now'. The Verve saw an overwhelming increase in popularity overseas; it reached the US top 30, going platinum in the process, and 'Bittersweet Symphony' reached number 12 on the US charts, their highest ever American position.

By November, the band released ‘Lucky Man’ in the UK, where it reached number seven on the charts. In an interview with BBC Radio 2, Richard Ashcroft revealed that the song was “inspired by my relationship with my wife, and that sense of when you’re beyond the sort of peacock dance that you have early on in a relationship, and you’re getting down to the raw nature of yourselves.”

Built around windswept strings and subtle ambient textures, ‘Lucky Man’ fills the emotional space where McCabe’s guitar storms once raged. It’s another melancholic masterpiece, one of the album’s towering peaks. This isn’t just a great song of its time; it’s an exceptional song, period. Few bands ever write something so emotionally resonant, so effortlessly timeless.

‘Lucky Man’ captures the heart of ‘Urban Hymns’: the balance between grandiosity and vulnerability, between self-doubt and transcendence. It’s a song that feels both intimate and universal, steeped in reflection yet bursting with hope. That’s why the album continues to be passed down through generations because it speaks to the enduring human search for meaning, connection, and grace amid chaos

'Urban Hymns' is a grand affair; it still sits pretty among the UK’s all-time top twenty best-selling albums, ahead of such ubiquitous contenders as '25' and 'The Joshua Tree'. It earned them the Best British Group and Best British Album prizes at that year’s BRITs, as well as Grammy and Mercury nominations. It scored them a number one single in ‘The Drugs Don’t Work’ at a time when only Oasis, U2 and Blur were taking guitars to such chart heights. Perhaps more remarkably, it became a hit album in the US, going platinum stateside on the way to its 10 million-plus global sales. Suffice to say, when the band split after the release of their previous album 'A Northern Soul', even Richard Ashcroft’s most quixotic ambitions couldn’t have reached this far.

The Verve were not making the same mistakes that Ashcroft’s old brother-in-arms, Noel Gallagher, was when concurrently recording 'Be Here Now'. The expansive, indulgent largesse came not from a drug-induced numbness to their own shortcomings, but from an insatiable desire to cram their entire record collection into one album-length statement.

At the start of 1998, Hut wanted to release another single from the album, an idea which the band disagreed with. Unusually, Hut pressed them on this matter, and so the band finally agreed to release 'Sonnet', but only in a format that would make it ineligible for chart recognition. Consequently, 'Sonnet' was released as part of a set of four 12-inch records (backed by 'Stamped', 'So Sister' and 'Echo Bass').

The release of 'Sonnet' was limited to just 5,000 copies, despite the huge radio coverage it received, and the UK's Official Charts Company refused to recognise it as a single because of the extra content, as planned. The pack was released in a cardboard mailer, and the preceding three singles from the album were all re-released on the same day, fitted into the mailer. However, sales of an imported format resulted in it charting in the United Kingdom at number 74. The song also charted in Australia, Iceland, and New Zealand, reaching numbers 83, 4, and 43, respectively.

'Sonnet' is a plea for personal salvation and is the sound of a man falling in love, begging for some recognition. "Sinking faster than a boat without a hull," moans Ashcroft as sweeping strings whip the gentle rhythm to a misty climax, "dreaming about the day I can see you by my side... Yes, there's love if you want it".

It's exceptional. The four singles from this album rival any other '90s band. From Nirvana to Oasis. These are just as good, if not better.

The singles were outstanding, but ‘Urban Hymns’ is much more than a collection of hits; it’s 1 hour and 15 minutes of exceptional music spread across 13 songs. ‘Weeping Willow’ and ‘Space and Time’ are expansive, ethereal laments that sit effortlessly alongside ‘Lucky Man’ and ‘Sonnet’, each one balancing vulnerability with grandeur. ‘The Rolling People’ is an all-out, bombastic psychedelic masterpiece taking everything we’d heard from The Verve before, turning it up to eleven, and then running it through four effects pedals for good measure. The result is staggering.

‘Come On’, named after Ashcroft’s own onstage battle cry, closes the album with a ferocious sense of purpose. He described it as “a battle cry for those who need to hear it,” and the song lives up to that spirit. Featuring backing vocals from Liam Gallagher, it stands as one of the most aggressive and electrifying tracks The Verve ever recorded, channelling the raw energy of Led Zeppelin, MC5, and The Stooges into something entirely their own.

In 1997, The Verve were a force of nature; they'd knocked the biggest band in the world off the top spot, and set about capturing the fire in the bottle out on the road.

In the lead-up to the Verve's first live show in nearly two years, Ashcroft was in pain while they rehearsed. The gig at The Leadmill in Sheffield on 14 June 1997 was cancelled a few days before it took place. It was discovered that because of the stress of the recording sessions, Ashcroft had swollen lymph glands in his neck, which caused issues when he tried to sing, eventually leading to him collapsing. He told the NME that he was not interested in the show to start with, while the rest of the band were. When he went to a doctor, he was recommended to cease working for six weeks, resulting in the cancellation of other shows in June 1997 and forcing new shows to be booked for later in the year.

The band finally returned to live performances on 9 August 1997 at The Leadmill. After some more shows, they performed at the Reading Festival, where they headlined the Melody Maker stage.

Following a month's break, they supported Oasis for three shows at Earls Court in London, between 25 and 27 September 1997, to a collective crowd of 60,000. After another month's break, the Verve embarked on a US tour; around this time, 'Bittersweet Symphony' became a hit in the US. The trek consisted of 12 dates, ending in late November 1997. Tickets for European shows, which went on sale by the end of the year, had sold out within two hours. At the start of 1998, the band went on a UK tour of mid-sized venues, despite being able to fill arenas at this stage. Instead of appearing at the Brit Awards, they played at a homelessness benefit that same night.

On 24 May 1998, The Verve performed a one-off homecoming show at Haigh Hall in Wigan, Greater Manchester, in front of nearly 40,000 fans. The tickets sold out within hours, and for those who managed to get one, it felt like a pilgrimage, a chance to see the local heroes return as conquering icons. Supported by John Martyn and Beck. This was The Verve at their very best.

Opening the show with 'This is Music'.

“I stand accused just like you,

For being born without a silver spoon,

Stood at the top of a hill

Over my town, I was found”

This is them, stood over the hill of their home town Wigan, just over the road from the pub that they first played, now in front of 33,000 people, in the wave of Urban Hymns and its unstoppable force since its release late in the year before, this was finally The Verve’s moment……

It was the band at their peak. Playing all of the hits, fans got the best of 'Urban Hymns' and 'A Northern Soul'. The song that some say has been stolen, 'Bittersweet Symphony', and the exceptional 'Lucky Man', dedicated to Ashcroft's wife. ‘The Rolling People’ BOOM, this song is a manifesto, from Ashcroft to the people, COME ON, HAVE IT’ Ashcroft riffing all over on this, chanting, channelling energy. 'History' as the penultimate song, and the crushing 'Come On' brought the show to an end.

It wasn't on the same scale as Knebworth or Maine Road, but it was The Verve's moment, a moment that they deserved.

The band then played gigs in mainland Europe, but, on 7 June, a post-show fight at the Philips Halle in Düsseldorf, Germany, left McCabe with a broken hand and Ashcroft with a sore jaw. After this, McCabe decided he could not tolerate the pressures of life on the road any longer and pulled out of the tour, leaving the band's future in jeopardy, with rumours of a split circulating in the press. The band continued with session musician B. J. Cole replacing McCabe, whose guitar work was also sampled and triggered on stage. The band played another American tour, which was riddled with problems as venues were downsized and support act Massive Attack dropped out. The band returned to England for two headline performances at V Festival, which received poor reviews; NME wrote that "where songs used to spiral upwards and outwards, they now simply fizzle tamely". The Verve played their last gig at Slane Castle in Ireland on 29 August. A long period of inactivity followed. In February 1999, 'Bitter Sweet Symphony' was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Rock Song. Finally, in April 1999, it was announced that The Verve had again split up.

It had broken the band, they'd become the biggest band in Britain, and it had blown up just as quickly as it started.

A Song for the Lovers: 2000-2006

By the time The Verve had split, Ashcroft was already working on solo material accompanied by, among others, Salisbury and Cole. In 2000, he released his first solo album, Alone with Everybody, which reached number 1 on the UK album charts.

Included on this album were 'A Song for the Lovers', 'C'mon People (We're Making It Now) and 'New York', all of which had initially been recorded by The Verve.

The former members sometimes expressed bitter sentiments about the band's later years. In his only interview after the split, McCabe said of Urban Hymns: "By the time I got my parts in there, it's not really a music fan's record. It just sits nicely next to the Oasis record."

During his solo career, Ashcroft expressed regret at having asked McCabe to return for the album instead of releasing it under his own name, saying: "Imagine being the guy that's written an album on his own, bottles it near the end, feels like there's unfinished business, rings Nick McCabe up who adds some guitars, puts it out as the Verve and the same problems arise again. Imagine being that mug. I've now got to rewrite history. Everyone thinks those songs are somehow associated with another bunch of people that I'm not with now." Jones claimed that "The Verve were going off in a direction of strings and ballads, and that's not where I was coming from at all. Loud guitars are it for me," though noting that this was not why the band split up.

Ashcroft continued to release solo material, which was patchy at best; there are some good songs in there, 'Music is Power', and 'Break the Night with Colour' being standouts, but it wasn't The Verve. However, he'd made his thoughts clear on a reunion.

"You're more likely to get all four Beatles on stage".

Cause 'Love Is Noise' 2007-2008

After Ashcroft learned that Salisbury was in contact with McCabe over a possible side project, Ashcroft contacted McCabe and Jones, making peace with them, and the band re-formed. Tong was not asked to rejoin, so as to keep the internal issues that split the band up a decade ago to an absolute minimum. Jones explained this decision by stating: "It would have been too hard, it's hard enough for the four of us. If you bring more people to it, it's harder to communicate and communication has always been our difficulty". Paradoxically, McCabe would state years later on his Twitter account that he intended to include the electric violinist and arranger Davide Rossi as a new member of the group.

On 26 June 2007, the band's reunion was announced by Jo Whiley on BBC Radio 1. The band, reuniting in their original line-up, announced they would tour in November 2007 and release an album in 2008. The band stated: "We are getting back together for the joy of music", though they turned down a multi-album deal offer "because the 'treadmill' of releasing albums and touring marked the beginning of the end for the band a decade ago".

Tickets for their six-gig tour in early November 2007 sold out in less than 20 minutes. The tour began in Glasgow on 2 November, and included 6 performances at the Carling Academy Glasgow, The Empress Ballroom and the London Roundhouse.

Since the 6-gig tour went extremely well in sales, the band booked a second, bigger tour for December. They played at the O2 Arena, the SECC in Glasgow, the Odyssey in Belfast, the Nottingham Arena and Manchester Central. Each show from the first and second parts of the tour was sold out immediately. The band continued touring in 2008. They played at most of the biggest summer festivals and a few headline shows all over North America, Europe, Japan and the UK between April and August. Including shows at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, also at the Madison Square Garden Theatre, and the Pinkpop festival, Glastonbury Festival, T in the Park, the V Festival, Oxegen Festival, Rock Werchter, Rock am Ring and Rock im Park and The Eden Project Sessions.

'Love Is Noise' was premiered by Zane Lowe on the 23rd of June 2008, on his Radio One show. Performing at Glastonbury six days later on June 29th. Closing the show with the new song.

The band announced the new album's title: Forth, which was released in the UK on 25 August and the following day in North America. The album reached No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart on 31 August. The lead single 'Love Is Noise' was released in the UK on 3 August digitally and one week later (11 August) in its physical form, peaking at No. 4 in the UK.

The song reworks lines from William Blake's poem "And did those feet in ancient time", commonly known as 'Jerusalem'. Where Blake begins "And did those feet in ancient time, / Walk upon England's mountains green?", 'Love is Noise' asks: "Will those feet in modern times / Walk on soles that are made in China?", and alludes to "bright prosaic malls" in place of "dark Satanic Mills".This is the second time Richard Ashcroft has referenced Blake, following 1995's 'History'

'Rather Be', the second single from the album, was released in November but did not become as successful as "Love Is Noise" was, peaking at number 56 on the UK Singles Chart.

'Forth' received relatively good reviews; it has been built on a fairly good foundation. Fans hoped that it would be a springboard for several more records, but it wasn't to be.

All Farewells Should Be Sudden: 2009 to today

In August 2009, The Guardian speculated that The Verve had broken up for a third time. The Verve don’t drag things out. Their biggest single before ‘Urban Hymns’, 1995’s ‘History’, had already declared that “all farewells should be sudden,” and in true Verve fashion, their first split was exactly that clear, uncompromising, and final. Their “hellos” were just as sudden: spontaneous bursts of creativity that burned bright and fast before collapsing under the weight of ego, exhaustion, and expectation. The reunion that bore ‘Urban Hymns’ had lasted barely twelve months, yet it left behind one of the defining albums of the decade.

By the time of their 2007 reunion and subsequent ‘Forth’ album, the same old fractures were already beginning to show. What began with promise and nostalgic excitement soon turned cold. Reports from inside the camp spoke of tension, creative control battles, and old resentments rising to the surface. Jones and McCabe were no longer on speaking terms with Ashcroft, frustrated by what they saw as his using the band as a vehicle to reignite his solo career. There was a sense that the magic of the past couldn’t be recreated, not because the songs weren’t there, but because the chemistry that made them possible had long since eroded.

When asked about the supposed split, Ashcroft told The Daily Telegraph: “I can confirm we did what we set out to do. Right now, there are no plans to be doing anything in the near future.” It was a typically understated farewell, the kind that implied closure without ceremony. For a band that built its legend on intensity and transience, it felt almost fitting. The Verve had once again burned themselves out, leaving behind a legacy of music that remains timeless, and a story that continues to echo with what-ifs.

Their endings were never clean, but perhaps that was part of their mystique. Every breakup felt like a natural aftershock to the emotional and creative force that held them together. Few bands have lived so close to the edge, or produced such transcendent music while standing in the fire. And so, true to their own lyric from ‘History’, The Verve’s final farewell was sudden, abrupt, poetic, and absolutely theirs.

Legacy:

The Verve’s legacy rests on a remarkable paradox: a band that often teetered on the edge of collapse yet consistently produced music of enduring emotional and artistic weight. Their first three albums, ‘A Storm in Heaven’ (1993), ‘A Northern Soul’ (1995), and ‘Urban Hymns’ (1997) chart an evolution from ambitious psychedelia to introspective, emotionally charged Britpop, each stage marked by unforgettable songs that continue to resonate decades later.

‘A Storm in Heaven’ introduced the world to The Verve’s expansive, atmospheric sound. Tracks like ‘Blue’ and ‘Slide Away’ showcased Nick McCabe’s swirling, hypnotic guitar work and Richard Ashcroft’s yearning vocals, setting the tone for a band unafraid to explore both space and emotion. While not a commercial juggernaut, the album earned the band critical acclaim and a devoted following, establishing them as innovators capable of turning experimentation into something transcendently human.

‘A Northern Soul’ was built on that foundation, bringing Ashcroft’s songwriting into sharper focus. Songs like ‘History’ and ‘This is Music’ combined introspection with raw power, revealing a band that could be both intimate and monumental. The album solidified The Verve as a major creative force in the UK music scene, balancing lyrical depth with an evolving sense of grandeur.

Then came ‘Urban Hymns’, the record that would define their career. With anthems such as ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’, ‘Lucky Man’, ‘The Drugs Don’t Work’, and ‘Sonnet’, The Verve reached the peak of their creative and commercial powers. ‘Urban Hymns’ has come to be seen as the swan song for Britpop’s cultural hegemony. But in 1997, it felt like a step forward.” The album’s sweeping orchestration, ambitious arrangements, and emotional honesty resonated across generations, cementing the band’s reputation as one capable of blending grandeur with vulnerability. ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’ remains a cultural landmark, especially here in the UK.

Even beyond their individual hits, the band’s influence can be felt in the way they bridged the gap between alternative rock and mainstream Britpop, inspiring countless acts to balance atmospheric soundscapes with deeply personal songwriting. The Verve’s first three albums, with their combination of innovation, ambition, and pure emotional resonance, left an indelible mark on British music, defining both the sound and emotional scope of a decade while remaining timeless in their impact.

I saw Richard Ashcroft support Oasis in the summer, and in a seven-song setlist, six of those were Verve songs. He has attempted to eclipse his former band, but in my opinion, he’s come nowhere near to doing it. The Verve captured something that Ashcroft alone, for all his talent and charisma, has never quite been able to recapture: that perfect alchemy between vision, emotion, and noise. Their legacy endures because, for a brief and brilliant moment, they made music that sounded infinite.

Thank you for reading

Jack