The Good Ship Albion

In the messy chronicles of British indie rock, few bands have captured the spirit of romantic rebellion and chaotic camaraderie quite like The Libertines. Their story is a tapestry woven from poetic ambition, fractured brotherhood, and a relentless chase after a mythical England they called ‘Albion’. This is the definitive account of their voyage to the edge and back.

Formation and Early Days (1997–2002): The Genesis of Albion

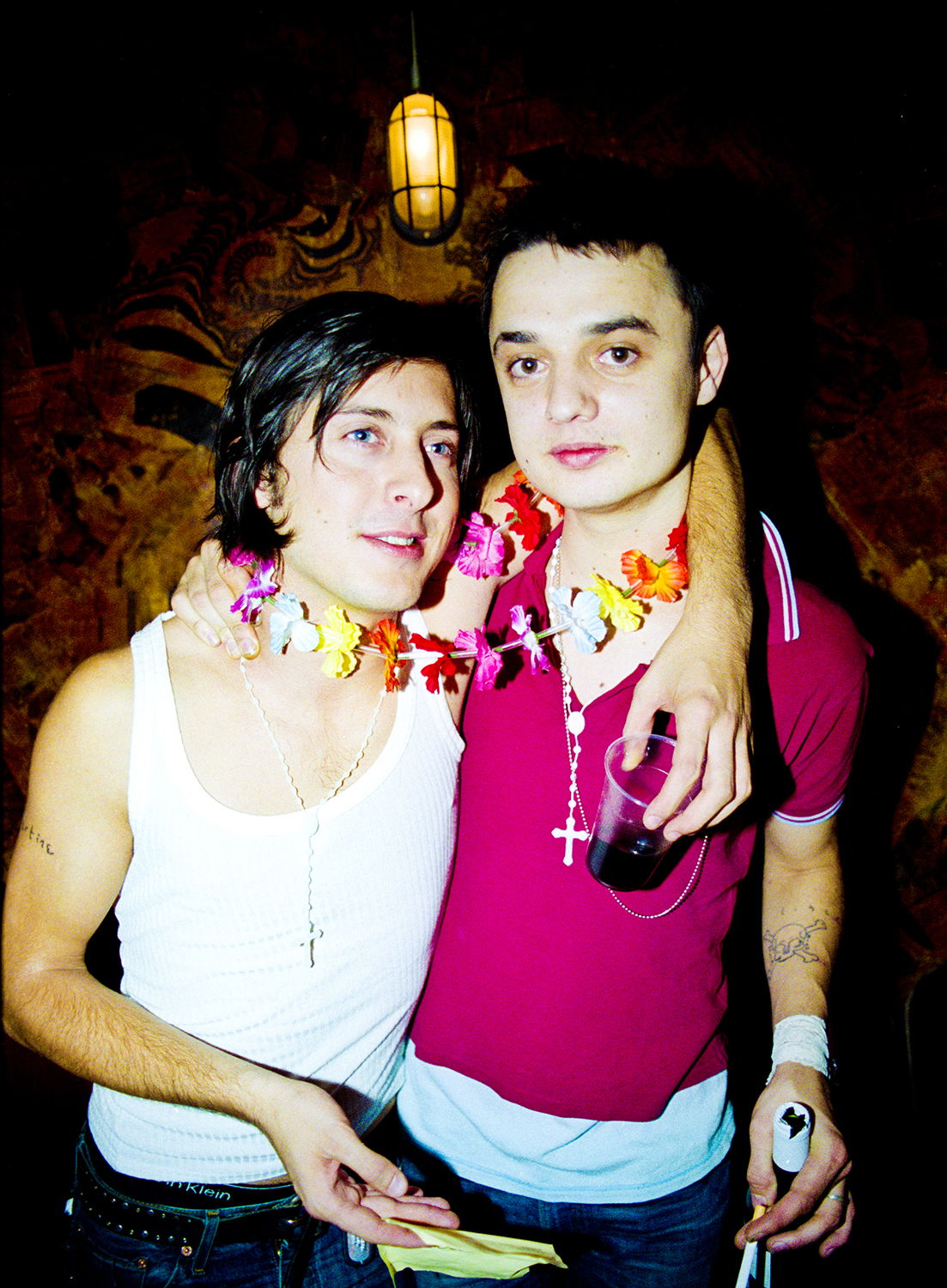

The story of The Libertines begins in the twilight of the 1990s, born from a serendipitous meeting between Peter Doherty and Carl Barât. At the time, Barât was studying drama at Brunel University while sharing a Richmond flat with Peter’s sister, Amy-Jo. The two men quickly found themselves anchored by a shared obsession with songwriting, graveyard poetry, and the romantic ideals of a bygone England. The creative pull was so strong that both abandoned their studies, Barât after two years at Brunel and Doherty after just one year of English Literature at Queen Mary, to move into a shared flat on Camden Road. They christened this first sanctuary “The Albion Rooms.”

Their early days were defined by experimentation and a revolving door of collaborators. Alongside their neighbour Steve Bedlow, affectionately known as “Scarborough Steve”, they initially performed under the name 'The Strand'. However, seeking a title that matched their transgressive spirit, they eventually settled on “The Libertines,” inspired by the Marquis de Sade’s unfinished and controversial work, The Lusts of the Libertines. While names like 'The Albions' were briefly considered, the chosen moniker better suited the duo’s burgeoning philosophy: a blend of bohemian excess and poetic rebellion.

Within the walls of the original Albion Rooms, the lines between art and life blurred. Doherty and Barât developed an intense, almost telepathic bond, famously describing themselves as two halves of the same soul. They began crafting a private mythology centred on ‘Albion’, a utopian vision of England where the constraints of modern society dissolved into a dreamscape of gin palaces, Blakean poetry, and absolute freedom.

As their reputation for chaotic, heartfelt performances grew through word of mouth, the need for a stable lineup became undeniable. The formative years saw a parade of musicians, most notably John Hassall and Johnny Borrell. While Borrell’s tenure was short-lived, he would later find fame fronting Razorlight; Hassall’ss melodic sensibility made him an essential, if periodically estranged, part of the band’s DNA.

By 2000, they had attracted the attention of Banny Pootschi, a lawyer for Warner Chappell. Under her guidance, the band recorded 'Legs XI', a raw demo compilation that captured the tender, unpolished heart of their sound. Despite the strength of tracks like the wistful 'France' and the jagged energy of 'Bangkok', the band remained unsigned by the end of the year, leading to a brief hiatus where Pootschi, Hassall, and original drummer Paul Dufour stepped away.

The global explosion of The Strokes in 2001 revitalised the UK guitar scene, prompting Pootschi to return with a rigorous six-month strategy known as “Plan A.” The goal: get signed to Rough Trade Records. To sharpen the band’s edge, Dufour was replaced by drummer Gary Powell, whose powerhouse energy provided the necessary grit for their evolving sound.

The turning point came during a showcase for Rough Trade’s James Endeacott. Johnny Borrell, the bassist at the time, famously failed to show up for rehearsal, claiming he was "living the high life" on tour elsewhere. He was promptly dropped, and the duo performed a stripped-back set that blew Endeacott away. After a second showcase for label legends Geoff Travis and Jeanette Lee, a deal was finalised on 21 December 2001.

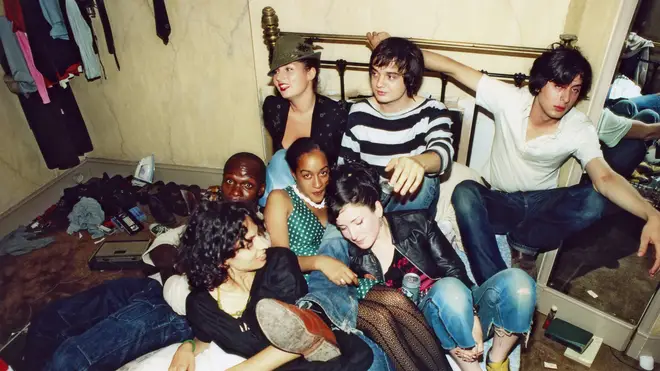

With a label behind them and John Hassall back on bass, Doherty and Barât moved to 112a Teesdale Street in Bethnal Green. This new iteration of “The Albion Rooms” became the epicentre of the Libertines mythos. It was more than a flat; it was a community hub for "guerrilla gigs" where the barrier between the band and the fans was nonexistent.

Reflecting on these sessions years later for a Radio X special celebrating the 20th anniversary of 'Up the Bracket', the band recalled the wild, frontier-like atmosphere:

Carl: "Culturally it was really significant in terms of community... and there was a more mercantile aspect to it."

Pete: "Yeah, we were putting tenners on the door. We made it so that refreshments could be supplied for all."

Gary: "To be honest, I thought it was mental. I remember turning up to one where the neighbour upstairs tried to break the door down with an axe."

These raucous, impromptu gatherings—funded by "tenners on the door"—cemented The Libertines as the face of a new British rock movement. They were messy, magnetic, and unmistakably real, turning the pursuit of ‘Albion’ into a lived reality for a generation of fans.

By the summer of 2002, the buzz surrounding the band had reached a fever pitch. To capitalise on the momentum, they released their debut single, 'What a Waster', in June. Produced by Bernard Butler of Suede, the track was a high-velocity, foul-mouthed broadside that perfectly captured their energy. Despite a near-total ban from daytime radio due to its liberal use of profanity, the single clawed its way into the UK Top 40. It was a pivotal moment: a raw, two-minute manifesto that proved The Libertines weren't just a Camden myth—they were a legitimate force. It served as the final, rowdy punctuation mark on their era of independence before they headed into the studio to record their full-length debut.

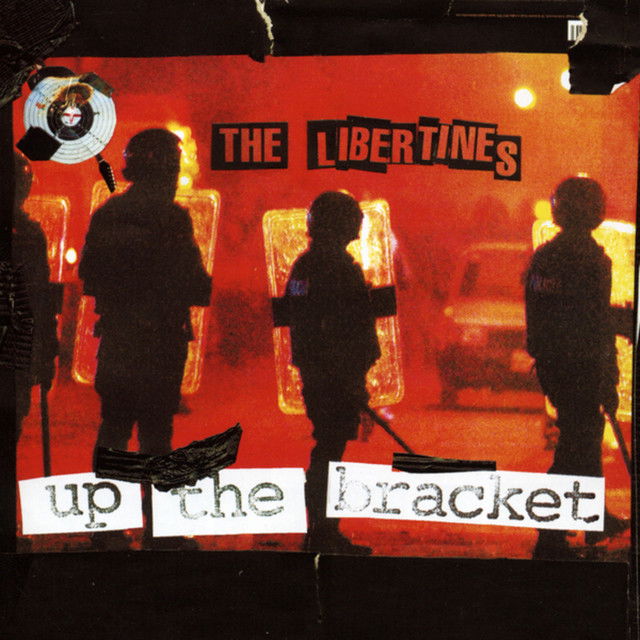

‘Up the Bracket’ (2002): A Raw Declaration

Released in October 2002, 'Up the Bracket' was produced by Mick Jones of The Clash, a pairing that felt like a spiritual passing of the torch. Jones’s guidance was instrumental; he didn’t just tolerate their chaotic charm, he curated it. Sessions were famously unpredictable, mirroring the emotional volatility of Doherty and Barât’s relationship. Fights, laughter, and sudden creative breakthroughs were common, resulting in a recording process as electric as the songs themselves.

The Libertines approached the album with a defiant disregard for polish. Takes were chosen based on raw feeling rather than technical perfection, turning the studio into a pressure cooker of drunken honesty and unfiltered emotion. The result was a record that didn't just announce the band; it felt like an incursion, a swaggering statement that resurrected the spirit of The Jam and The Smiths for a disenchanted new generation.

The album propelled the twin ideals of Albion and Arcadia into the national consciousness through a collection of now-legendary tracks. 'Vertigo' opens the record as a whirlwind of jagged guitars and impending chaos, perfectly capturing the thrill of a life teetering on the brink. This energy transitions into the more melodic yet sombre 'Death on the Stairs', a melancholic reflection on love and loss that showcases Doherty’s lyrical depth and Barât’s instinct for harmony through their signature call-and-response vocals.

Perhaps the album’s defining anthem is 'Time for Heroes', which distils the band’s ethos into three minutes of blistering urgency. Inspired by Doherty’s firsthand experience of police brutality during the London May Day riots, the track became a rallying cry for a generation bored by apathetic pop culture. With iconic lines like "Did you see the stylish kids in the riot?", the song romanticised civil unrest as a stage for poetic defiance.

Doherty’s lyrics masterfully juxtaposed the grim reality of the streets with a dandyish, literary flair, sneering that "there are fewer more distressing sights than that of an Englishman in a baseball cap." It was a rejection of the "chav" caricatures and the sterile, polished "Cool Britannia" leftovers of the late 90s. Instead, the song offered a return to a more traditional, ragged elegance. The interplay between Barât’s aggressive, melodic guitar work and the breathless pace of the rhythm section gave the track a sense of "now or never" importance. It wasn't just a song about a riot; it was a manifesto for those who felt that the only way to find beauty in a broken Britain was to create a little chaos of their own. For the fans, 'Time for Heroes' cemented the band as the true voice of a new, disenfranchised underground.

The title track, 'Up the Bracket', serves as a punchy critique of urban violence and societal constraints, blending punk intensity with gritty London street poetry. The phrase itself, slang for a punch to the throat, perfectly mirrored the band’s confrontational yet artful presence. It captures a paranoid, high-speed chase through the back alleys of London, where "two shadow-men" lurk and the threat of a "leather jacket" or a "stick in the hand" feels visceral. It was the sound of the city’s underbelly transformed into a frantic, melodic hook.

Rounding out the sonic landscape, 'Tell the King' and 'Boys in the Band' offer an introspective look at the cost of ambition and a tongue-in-cheek jab at the groupie scene, all while maintaining the band's signature "shambolic-yet-tight" sound. 'Tell the King' slows the pace just enough to reveal the band’s more vulnerable, melodic core, posing existential questions about fame and the fear of the dream ending too soon. Meanwhile, 'Boys in the Band' is a self-aware, rollicking nod to the lifestyle they were quickly being consumed by, mocking the very industry that sought to commodify them. These tracks, alongside the frantic energy of 'The Boy Looked at Johnny' and the nostalgic yearning of 'The Good Old Days', solidified the album as a cohesive journey through the highs and lows of the human condition, all seen through a cracked, bohemian lens.

The album’s rough charm was a breath of fresh air, but success didn’t temper the band's volatility—it magnified it. As their popularity grew, the magnetism between Doherty and Barât began to combust. Libertines gigs became notorious for their unpredictability; audiences never knew if they were witnessing a transcendent performance or a literal on-stage implosion. Often, the band would invite the entire audience back to their flat after a show, further blurring the line between the stars and the fans, but this lack of boundaries only added to the mounting pressure.

This increasing profile only accelerated a dark descent. Doherty’s deepening struggle with addiction, specifically crack cocaine and heroin, began to strain the band to its breaking point. His erratic behaviour and frequent disappearances created deep rifts, often leaving Barât to shoulder the weight of the band’s obligations alone. The poetic brotherhood that had built the dream of Albion was beginning to fracture under the crushing weight of mistrust and the relentless pressures of fame. The very chaos that made them the most exciting band in Britain was now the very thing threatening to tear them apart.

The Frature: Betrayal and Wandsowrth (2003–2004): The Albion Hits the Rocks

As The Libertines’ fame surged, so too did the internal fractures threatening to tear them apart. At the centre of the turmoil was Pete Doherty’s growing dependence on crack and heroin, which increasingly alienated him from the band and strained his once-unbreakable bond with Carl Barât. What had begun as a partnership built on poetry, punk, and unshakable trust had devolved into a volatile, heartbreaking spectacle of self-destruction, betrayal, and spiralling paranoia. Their once-idealistic vision of ‘Albion’, their shared dream of freedom and brotherhood, was now clouded by secrecy, missed rehearsals, and mounting resentment.

The most infamous rupture came in July 2003. While the rest of the band were touring Japan without him, a decision made by the group's management to force Pete to confront his issues, Doherty felt isolated and abandoned. Consumed by drug-fueled paranoia, he broke into Barât’s flat at 44a Mayton Street. In a desperate attempt to fund his addiction, he stole several personal items, including an antique guitar, a laptop, a harmoncia and a video recorder.

Doherty eventually confessed the theft to his then-girlfriend, singer Lisa Moorish, in a moment of guilt and unravelling desperation. The betrayal was devastating. For Barât, it wasn’t just a crime; it was a fundamental violation of the "Arcadian" pact they had sworn to uphold. Doherty was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison, eventually serving two months in Wandsworth. The image of the "Byronic hero" behind bars seemed almost too perfect a metaphor: a man imprisoned by his own vices, cut off from the world and the band that had become his identity.

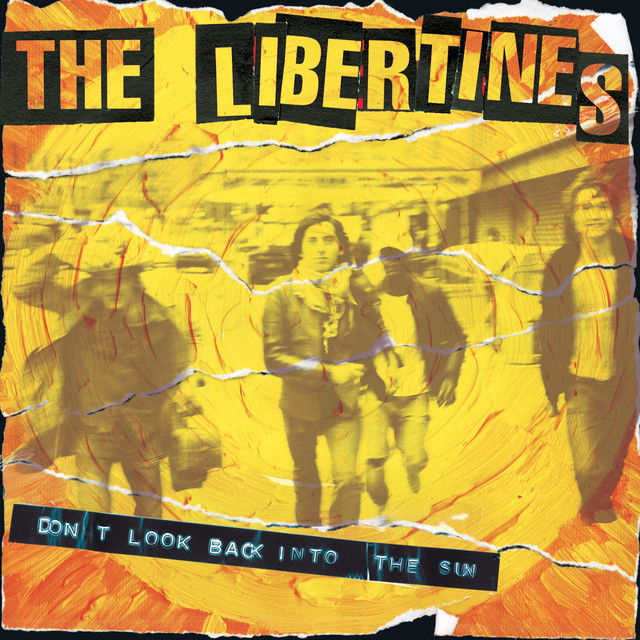

Released just weeks before his imprisonment, 'Don’t Look Back into the Sun' became the definitive high-water mark for The Libertines. Produced by Bernard Butler of Suede, the track was both an anthem and an elegy, its euphoric, major-key rush undercut by the prophetic melancholy baked into its title. It captured the band at their most sonically unified, even as the human elements were splintering.

Upon its release in August 2003, the single peaked at number 11 on the UK Singles Chart. It was a remarkable achievement for a band that still existed largely as cult icons, yet it received heavy airplay, resonating with a generation who saw in it a snapshot of a band burning too brightly. Despite its success, the band’s public performances were marred by Doherty’s absence. Most notably, The Libertines appeared on Top of the Pops to perform the song without him. Barât stood front and centre, singing alone, flanked by John Hassall and Gary Powell. The moment was surreal: a song born from the combustible chemistry of two "halves of the same soul" was now being performed as a fractured echo. It was a poignant, dissonant image of a band functioning on the surface but fundamentally incomplete.

Yet even in incarceration, the music remained a lifeline. Removed from the whirlwind of touring and toxic cycles, Doherty found himself stripped of everything but his desire to reconnect with his art. He famously struggled to obtain a guitar within the prison walls, taking weeks to finally persuade the authorities to let him have one. When he finally struck the strings, the first song he played was 'Don’t Look Back into the Sun'. Alone in his cell, strumming its jubilant chords against the cold backdrop of Wandsworth, Doherty reportedly broke down in tears, overwhelmed by a crushing cocktail of longing, guilt, and the sharp, inescapable ache of everything he had thrown away.

This period was defined by profound contradiction: public adoration and private implosion; brotherhood and betrayal. The Libertines had ceased to be just a band; they had become a living tragedy playing out in real time. Just as they should have been reaching their creative zenith, the dream of ‘Albion’ seemed to be turning into a nightmare. They were poised to be crowned legends, but instead, they were crumbling under the weight of their own chaos.

However, the story wasn’t over. The gates of Wandsworth were about to open, and what happened next would define the band’s legacy forever.

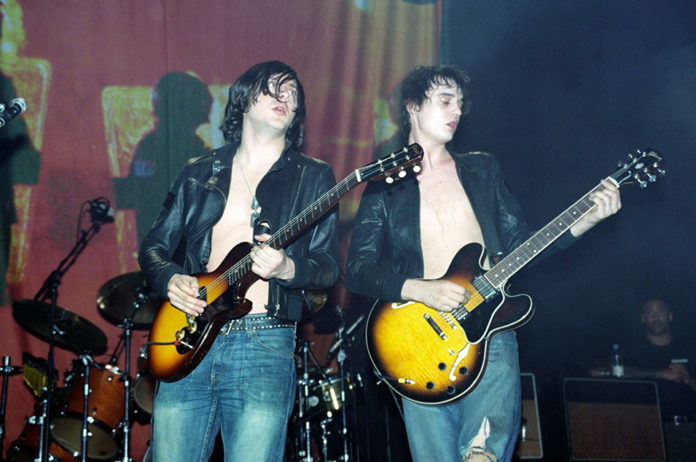

‘The Libertines’ (2004): A Band on the Brink

Despite a landscape of personal wreckage and constant turbulence, the band managed to record their self-titled second album, 'The Libertines', released in August 2004. The record stands as a raw, poignant reflection of a fractured relationship, its lyrics steeped in regret, longing, and the remnants of a brotherhood hanging by a thread. The sessions were chaotic, frequently interrupted by Pete Doherty’s absences, his battles with addiction casting a long shadow over the studio. Tensions were so high that security was eventually hired to keep Doherty and Barât from physically attacking one another. At times, the struggle between creation and destruction became indistinguishable; the band was essentially documenting its own demise in real-time.

A major turning point in the band's mythology occurred shortly after Doherty’s release from Wandsworth. He rejoined the band for the "Freedom Gig" at the Tap 'n' Tin in Chatham, a chaotic, electrifying performance that served as a cathartic reunion with their fans. It was here that the now-iconic NME cover photo was captured: Doherty and Barât sharing a cigarette, leaning into each other with a mixture of tenderness and defiance. The image became the ultimate visual distillation of their mythos, two kindred spirits locked together, unable to fully coexist, yet unable to let go.

On the album itself, 'Can’t Stand Me Now' emerged as the defining anthem of their fractured partnership. More than just a song, it was a public reckoning, a raw, unfiltered duet that laid bare the messy tangle of their friendship. Structured as a musical argument, its conversational lyrics and call-and-response delivery felt less like a performance and more like two old friends finally saying the things they had left unsaid for too long.

The track was weighted with history, particularly during the harmonica solo played by Doherty. The instrument had taken on a strange, mythic symbolism: a year prior, Pete had stolen a harmonica from Carl’s flat during the burglary, but by Christmas 2003, Barât had gifted new harmonicas to the entire band. Pete was back in the band, so he got one too.

Seeing Pete play it on their biggest hit felt like a fragile olive branch held out in the middle of a storm.

The rest of the album continued this exploration of lost innocence. 'Music When the Lights Go Out' painted a sombre, dreamlike portrait of fading unity, with Barât’s vocals guiding a reflective lament about the collapse of ideals. In contrast, 'What Became of the Likely Lads' cast a bitter glance back at their early days, asking the titular question with a sting of regret. It was a song about youthful idealism curdling into disillusionment, a yearning for a world that could never be recaptured.

One of the album’s more haunting moments is 'The Man Who Would Be King'. Dense with intricate lyrics and steeped in a brooding, almost funereal atmosphere, the song feels like a slow-motion collapse. It served as a portrait of self-destruction, mirroring Doherty’s spiral and his painful awareness of the myth he was both chasing and becoming trapped within. Meanwhile, 'Campaign of Hate' delivered a scathing critique of the external pressures surrounding them, the music industry, the press, and the suffocating weight of a public scrutiny that had warped their sense of identity.

Despite the ghosting absences and the near-collapse of the sessions, the album was a triumph of unfiltered honesty. NME heralded it as "some of the most exhilarating and brilliant rock’n’roll of the past 20 years," correctly predicting that "we won’t see their like again."

The victory was short-lived. By the time the album was finished, the situation had become unsustainable. Doherty left the mixing and dubbing to the others, never to return to a studio with the band for over a decade. His attempts to combat his addictions were faltering; after two aborted stays at The Priory, he met with Barât, Hassall, and Powell at a London club on June 7, 2004. There, he informed them of his plan to travel to Wat Tham Krabok, a remote monastery in Thailand, to undergo a gruelling, unorthodox detox program.

It was a last-ditch effort to save himself, but it signalled the end of the band's golden era. After a short tour without Doherty to promote the release, the sun finally set on the original voyage of The Libertines.

Hiatus and Side Projects (2005–2009): Separate Paths

In the wake of the collapse, the two frontmen retreated into separate camps, yet both remained tethered to the wreckage of their shared dream. Pete Doherty formed Babyshambles, channelling his escalating struggles into a new, even more precarious musical outlet. Their debut album, 'Down in Albion' (2005), was a sprawling, unfiltered collection that served as a diary of Doherty’s ongoing battle with addiction and his desperate search for a sense of place.

The most striking track on the record was the title-adjacent ‘Albion’, a song that felt like a ghost haunting the tracklist. Originally written during the tail end of The Libertines' career and appearing in their earliest demo sessions, it had never been officially released as a Libertines track. However, its themes of pastoral decay and romantic longing fit perfectly with the emotional weight Doherty carried into this new era. ‘Albion’ was the spiritual successor to the poetic mythos they had built together, a melancholic tribute to a homeland that felt increasingly out of reach.

The song’s lyrics name-checked the geography of their shared history, from the "yellowing lines" of the railway to the "bus to the psycho ward", anchoring the myth of Albion in a gritty, recognisable reality. It felt less like a studio recording and more like a transmission from a man drifting further away from the shore. While ‘Fuck Forever’ provided the album with its raw, defiant energy and a cynical middle finger to the industry, it was ‘Albion’ that spoke to the soul of the fans. Its lush, wistful atmosphere and the sound of Doherty’s fragile, cracking vocals captured the very essence of what the band had stood for, even in their final, fractured days.

Its inclusion in 'Down in Albion' served as a poignant reminder of the creative gold that still existed within their fractured legacy. For many, the song was proof that while the band was dead, the vision was still alive, albeit in a more haunted, isolated form. It became a bridge for fans, a way to keep the dream of the "Good Old Days" alive while witnessing the slow-motion tragedy of the present. This era saw Doherty transform from a co-frontman into a polarising folk-hero figure, a modern-day Byron whose every move was documented by a predatory tabloid press, further blurring the line between his art and his increasingly precarious reality.

While Doherty was navigating his personal demons in the tabloids, Carl Barât was forging a more structured path with Dirty Pretty Things. Formed alongside former Libertine Gary Powell and bassist Anthony Rossomando (who had filled in for Pete during the final tours), the band offered Barât a chance to step out from the shadow of the Doherty saga. Their debut album, 'Waterloo to Anywhere' (2006), arrived with a sharp, punchy confidence.

The lead single, ‘Bang Bang You’re Dead’, showcased Barât’s biting wit and his ability to craft a tight, aggressive indie hit. Yet, for all its technical strength and chart success, critics and fans alike noted that it lacked the raw, spontaneous combustion of his previous work. The album carried the spirit of the era, but without the chaotic "other half" of the soul, the music felt more like a professional recording and less like a spiritual event. Barât had found liberation, but he was still carrying the heavy silence left behind by his former partner.

Despite their separate pursuits, the spectre of The Libertines haunted both men. Doherty's chaotic lifestyle, marked by a relentless cycle of arrests and rehab stints, often threatened to eclipse his music entirely. Yet, during his intimate, stripped-back acoustic sets, the magic would resurface. In those quiet moments, fans flocked to hear him play Libertines classics and unreleased gems, finding the same raw vulnerability that had first drawn them to the Camden pubs years prior.

Barât, conversely, found himself the de facto guardian of the band's legacy, often answering for Pete’s absence while trying to build a future of his own. The chemistry that had made them the most magnetic duo in Britain was a lightning strike that couldn't be manufactured in a new project.

Through the mid-2000s, the myth of The Libertines, rooted in poetic decay, fleeting youth, and tragic romance, refused to die. Both men continued to battle their internal demons and the external weight of their reputations, but for the fans, the story was far from finished. The dream of ‘Albion’ was bruised, but it hadn't yet been abandoned.

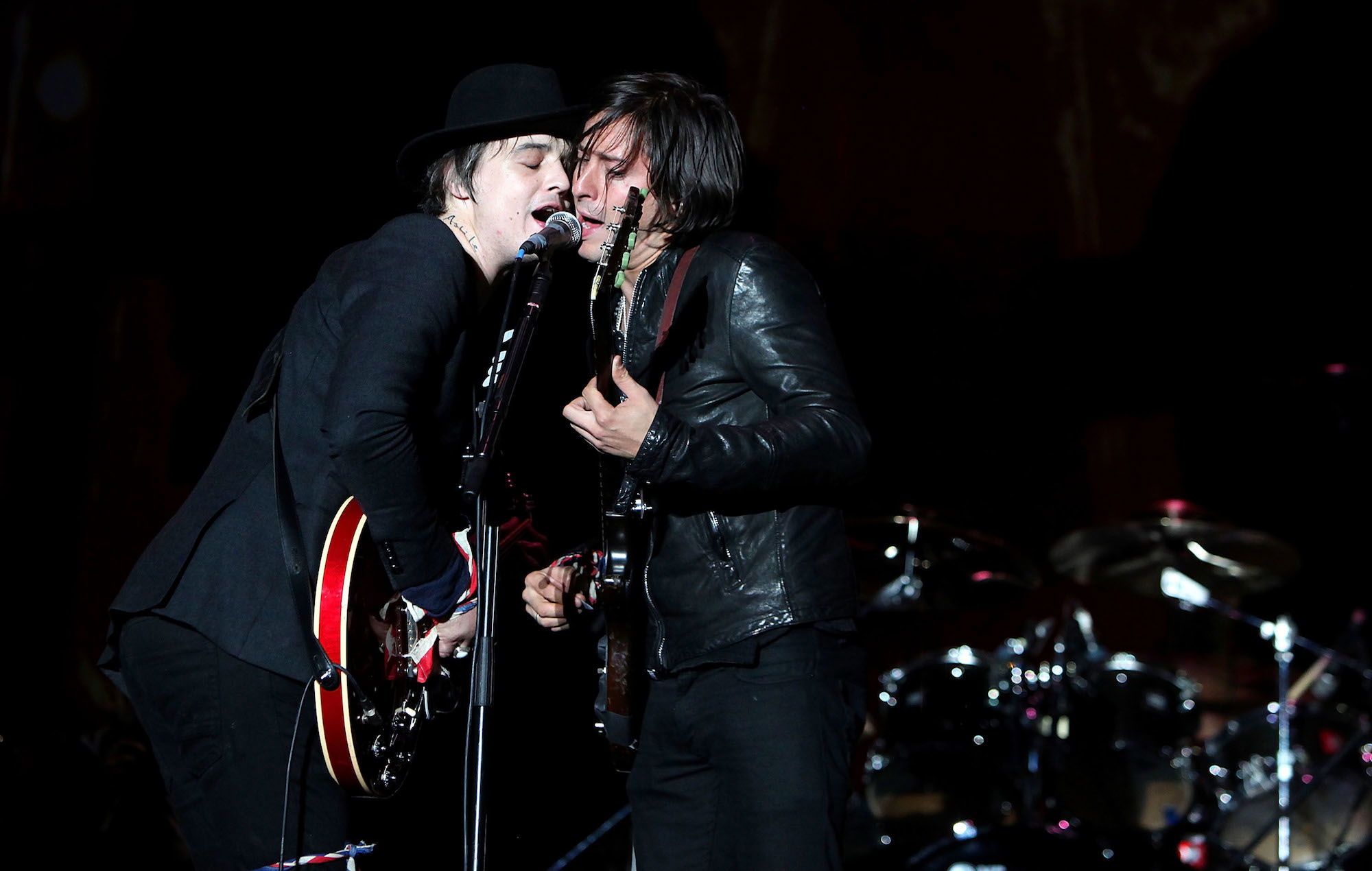

Reunion and Redemption (2010–2015)

When The Libertines announced their reunion in early 2010, it sent shockwaves through a music world that had long since resigned itself to their permanent collapse. After six years of fractured relationships and public struggles, the news was met with a volatile mix of euphoria and disbelief. They had once been the definitive symbol of chaotic brilliance, and their 2004 split had left a jagged void in British guitar music. Many wondered if the old magic could ever be recaptured, or if the years of turmoil had finally extinguished the "Arcadian" flame.

The band wasted no time reclaiming their reputation for unpredictability. On 31 March 2010, they held a press conference at the Boogaloo Pub in London to discuss their reformation. In true Libertines fashion, the formal event dissolved into a spontaneous "guerrilla gig." Picking up their instruments, they tore through their back catalogue for a room of stunned journalists and fans.

This was followed by two warm-up shows at the HMV Forum. The first, an intimate rehearsal for friends and family on 24 August, allowed the band to shake off the rust; the second, a sold-out fans-only show the following night, was the true litmus test. As Doherty and Barât shared a microphone once more, it became clear that the chemistry, that telepathic, combustible bond, remained intact. These weren't just rehearsals; they were a reawakening.

When they finally headlined the Reading and Leeds Festivals later that weekend, classics like 'Time for Heroes' and 'Don’t Look Back into the Sun' sounded less like nostalgia and more like a visceral, contemporary explosion.

The true milestone of their comeback arrived in 2014 with a legendary headline performance at London’s Hyde Park. Billed as a homecoming, the event was a curated celebration of the indie spirit, featuring a lineup that spanned generations, from The Pogues and Spiritualized to rising stars like Wolf Alice.

The gig itself was everything a Libertines show should be: messy, magnetic, and teetering on the edge of disaster. Crowds were so fervent that the show had to be paused multiple times due to safety concerns, but these interruptions only added to the sense of occasion. When they played 'Albion', with Doherty and Barât trading verses under the London sky, the years of estrangement and betrayal seemed to evaporate. It was the closest the band had ever come to reaching the mythical Arcadia they had dreamt of in their Camden flat a decade earlier.

In 2015, the band cemented their status as "super-subs" at Glastonbury, stepping in for the Foo Fighters. Amidst a sunset set that felt like a collective catharsis, they debuted 'Gunga Din', the lead single from their first new album in eleven years.

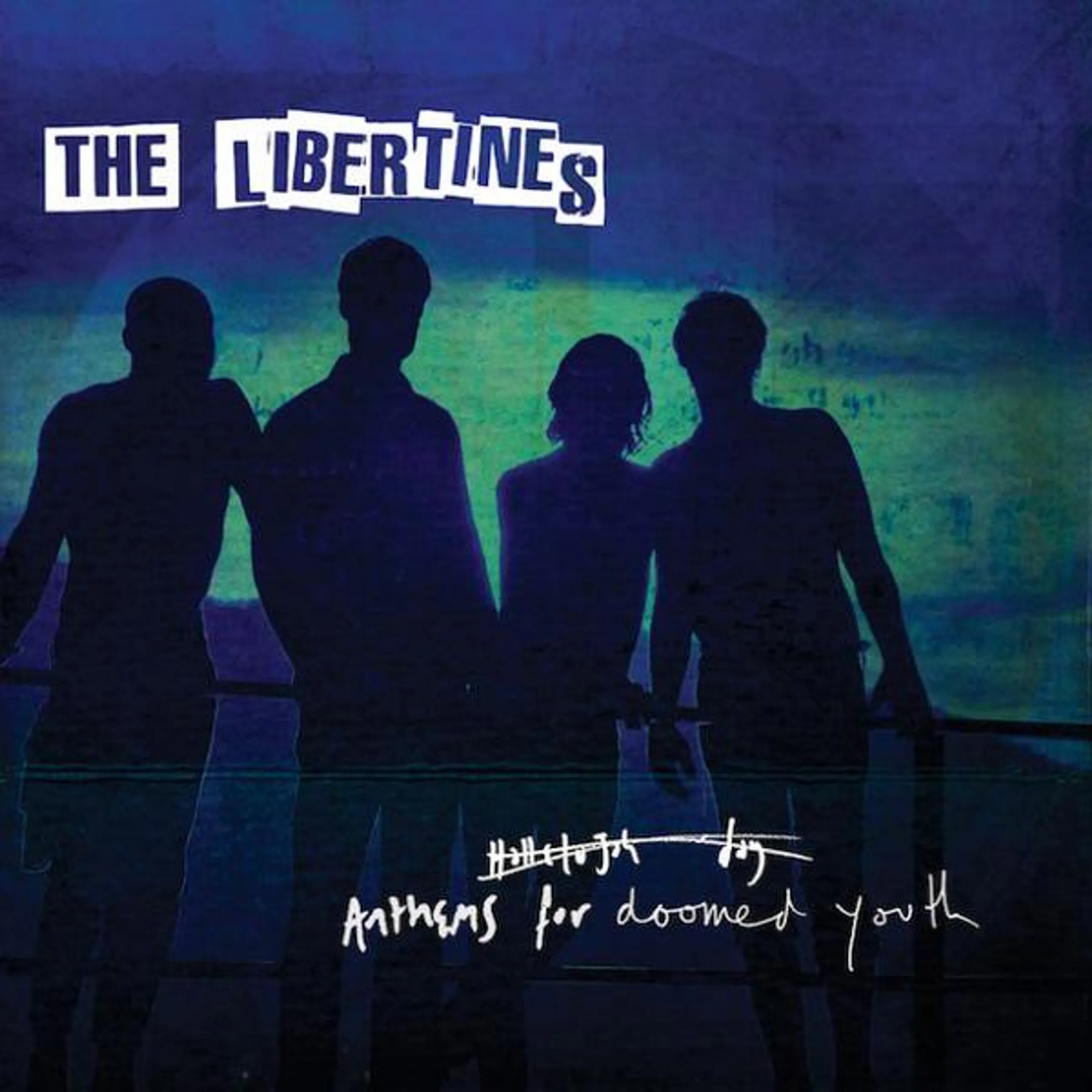

Recorded at Karma Sound Studios in Thailand, 'Anthems for Doomed Youth' (2015) represented a more reflective, mature version of the band. Produced by Jake Gosling, the record traded some of the old anarchic noise for a polished, soulful resonance. It was a redemption story captured in song, addressing themes of survival and reconciliation.

One of the standout tracks on the record is 'Gunga Din', which addresses the band's personal demons through a distinctive, reggae-inflected rhythm. The song’s title, borrowed from Rudyard Kipling’s poem, hints at a sense of duty and endurance amidst suffering. Lines like "the road to ruin is a long one" suggest a band finally coming to terms with their flaws and the cyclical nature of their struggles. It is a song that juxtaposes a sunny, laid-back musicality with deeply vulnerable lyrics, functioning as both a confessional and a rallying cry for those trying to navigate their way out of the darkness.

The album also finally gave 'You’re My Waterloo' a studio home, a legendary "lost" song that had been in the hearts of fans through bootlegs since the early 2000s. A tender, piano-led ballad, it serves as a quiet and profoundly moving acknowledgement of the enduring, albeit battered, bond between Pete and Carl. By placing this vintage piece of their history alongside their new material, the band bridged the gap between their youthful idealism and their weathered present. It remains one of their most intimate recordings, stripping away the noise to reveal the poetic core of their friendship.

In a more aggressive turn, 'Heart of the Matter' offers a confrontational critique of media intrusion and personal accountability. It shows a band that has become painfully self-aware, ready to face the consequences of their past while under the relentless microscope of the public eye. The track delves into the friction between the myth of The Libertines and the reality of their lives, refusing to shy away from the damage done during their years of estrangement. It is a sharp reminder that while they had found a way to work together again, the scars of their journey remained visible and served as the fuel for their renewed creativity.

The record is introduced by 'Barbarians', an opener that channels the band's original rebellious spirit through punchy riffs and a driving energy. It serves as a defiant statement of intent, proving that while they had grown and perhaps even found a measure of peace, they hadn't lost the "up the bracket" bite that defined their debut. The song questions the state of the world and the "barbarians" at the gate, suggesting that the only true sanctuary remains the music and the community they built. It was the perfect bridge for the album, signalling that the boys in the band were back, older and wiser, but still fueled by a restless, poetic fire.

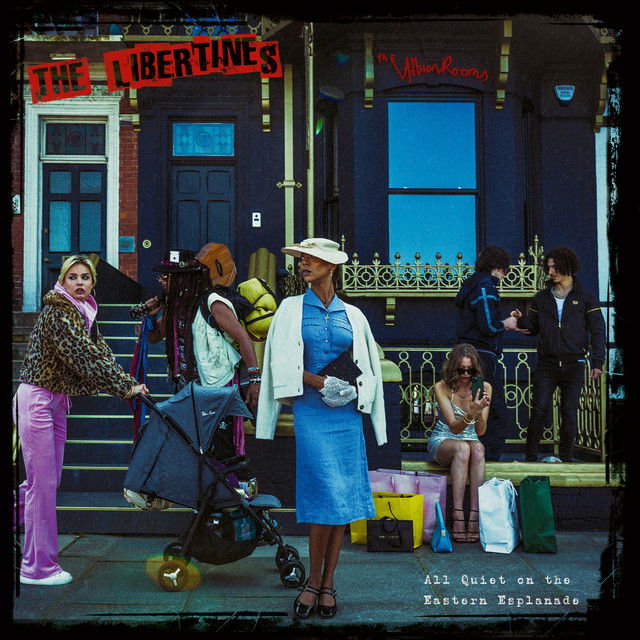

‘All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade’ (2024): A New Dawn

In 2024, two decades after they first crashed into the public consciousness, The Libertines returned with 'All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade'. This album feels less like a traditional comeback and more like a hard-won arrival at a destination they spent years trying to find. Named after the Margate seafront that has become their creative refuge, the record serves as both a reflection and a reckoning. It captures the sound of a band no longer at war with itself, but not entirely at peace either; they are older, wiser, and still chasing ghosts, but they are doing so with their feet firmly planted on the ground.

Recorded at their own Albion Rooms studio, once a poetic dream, now a bricks-and-mortar reality, including a hotel and bar, the album is drenched in seaside melancholy and post-recovery reflection. Where their earlier works burned with the frantic, scorched-earth desperation of youth, 'All Quiet on the Eastern Esplanade' breathes with the clarity of survival. There is still chaos lingering in the corners of the songwriting, but it is measured and deliberate. For the first time, The Libertines sound truly comfortable in their own skin, and the music is arguably better for it.

As the album’s urgent opener, 'Run Run Run' hits like a reawakening. Built on jagged riffs and a punchy tempo, it is The Libertines at their most electrifying, yet beneath the raw energy lies the mature tension between escape and endurance. The lyrics echo a lifelong instinct to flee, from pain, addiction, fame, and even the self, but unlike the breathless panic of their early years, there is a sense of mastery in the execution. It serves as a reminder that they haven’t forgotten how to set a room on fire; they’ve just finally learned how to keep the building from burning down.

One of the most ambitious and cinematic pieces in their entire catalogue is 'Night of the Hunter'. Drawing clear influence from the noir film of the same name, the track is a dark fable of temptation and pursuit, defined by creeping tension and a brooding atmosphere. There is a palpable menace in the guitars and a flickering paranoia in the rhythm, as if the band is recounting old sins under a streetlight in the rain. For a group that once lived dangerously on the edge, this song feels like a reflection from the shadows, showing a sophisticated depth to their storytelling that was only hinted at in the past.

The band’s enduring love for their homeland is revisited in 'Merry Old England', which echoes the social consciousness of 'Time for Heroes' but through a much more reflective lens. With its mid-tempo pace and sighing strings, the song acts as a welcome letter to migrants, showcasing a humanitarian maturity that the band wears seamlessly. This empathy continues in 'I Have a Friend', which serves as a poignant political olive branch to those suffering during the invasion of Ukraine. With haunting lines about tracks in the mud and the Black Sea being "black with blood," the song demonstrates that the band's gaze has shifted from their internal dramas to the world at large.

The emotional heart of the album is perhaps found in 'Shiver', a minimal and haunting track that stands as one of their most vulnerable moments. Doherty’s vocal delivery is delicate, almost brittle, as he explores themes of regret and emotional detachment. There is an intimacy here that recalls the rawest of their early solo demos, but the arrangement is far more deliberate. It doesn't build to a grand climax; instead, it lingers in a cold, quiet moment of reflection, suggesting that while not all wounds heal, they can finally be examined without flinching.

The album draws a beautiful circle back to their history with 'Songs They Never Play on the Radio'. A song born in 2006 but only finished for this record, it has quickly been hailed as one of the most beautiful Libertines tracks of all time. It is a testament to their tangible togetherness and the enduring camaraderie that has survived against all odds. Hearing them sing it feels like a privilege, the sound of a band finally comfortable with their position in the world.

This version of The Libertines: stable, creative, and unified, might be the best iteration of the band. They have moved beyond the tragedy of their own legend and emerged as masters of their craft, proving that the dream of Albion wasn't just a youthful fantasy, but a place they could eventually build for themselves.

Personal Struggles and Redemption: Doherty’s Journey

Few stories in modern music are as steeped in public tragedy and private triumph as Pete Doherty’s. For years, his name was synonymous with tabloid chaos and the agonising sight of a generational poet being reduced to a cautionary tale. Addiction to crack and heroin didn't just rob him of his health and the public's trust; it stole years of creative output, leaving fans to wonder if he would ever make it out of the "road to ruin" he so frequently sang about.

n the 2020s, however, a much quieter and more profound narrative took shape. Now living in rural Normandy with his wife, Katia de Vidas, and their young daughter, Doherty has carved out a life that once seemed impossible. This period of sobriety and stability has seen him swap the "burnt-out scooters" of his past for the serenity of the French countryside. Even the media’s focus on his physical changes has shifted; what was once sensationalised is now largely seen as a visible symbol of healing and a body finally at peace. In recent interviews, Pete speaks with a sharp, self-deprecating humour about his past, looking back not with pride in the chaos, but with a clear-eyed purpose for his future as a father and an artist.

His creative fire remains undimmed, though its fuel has changed. In addition to his work with The Puta Madres and a 2025 solo album, 'Felt Better Alive', Doherty recently embarked on a 20th-anniversary tour with a reformed Babyshambles. This reunion, fueled by a desire to honour the memory of the late Patrick Walden, proved that Pete could revisit his most turbulent material with a newfound strength. Today, he and Carl are on the best terms of their lives, co-parenting their legacy while preparing for a massive 2026 festival season. A fit and healthy Peter Doherty is no longer a miracle; it's expected, and he's still a cornerstone of the guitar music scene in Britain.

The Legacy of Albion: An Enduring Myth

At the heart of The Libertines’ story lies ‘Albion’, a mythical vision of England conjured from romantic poetry, the grit of the East End, and a uniquely British sense of dreamlike decay. It has never been just a setting for their songs; it is a spiritual compass that has guided them through every rise and fall. In the world of The Libertines, ‘Albion’ is where truth and fiction blur, a land where the Good Old Days aren't a time period, but a feeling found in a crowded pub or a shared microphone.

This myth is the band’s moral and creative centre, an ideal they have chased, lost, and rediscovered across two decades. From their earliest days scrawling lyrics in North London squats and navigating the lawless energy of Camden, to their current sessions in the salt-kissed air of Margate, the dream has endured. It is stitched into every off-kilter harmony and every ragged anthem. While the Arcadia they once sought was a place of total, reckless freedom, their version of it in 2026 is more tangible: it’s found in the community they’ve built at The Albion Rooms, where they now provide studio time to the next generation of likely lads.

As they sail into 2026, The Libertines appear more complete than ever before. They have moved past the need for the campaign of hate and the internal wars that nearly sank them. The "Good Ship Albion" is no longer a vessel taking on water; it is simply moving at its own weathered, dignified pace. With the wind in its tattered sails, the band continues to move toward a beautiful, strange horizon, older, arguably wiser, and finally, truly home.