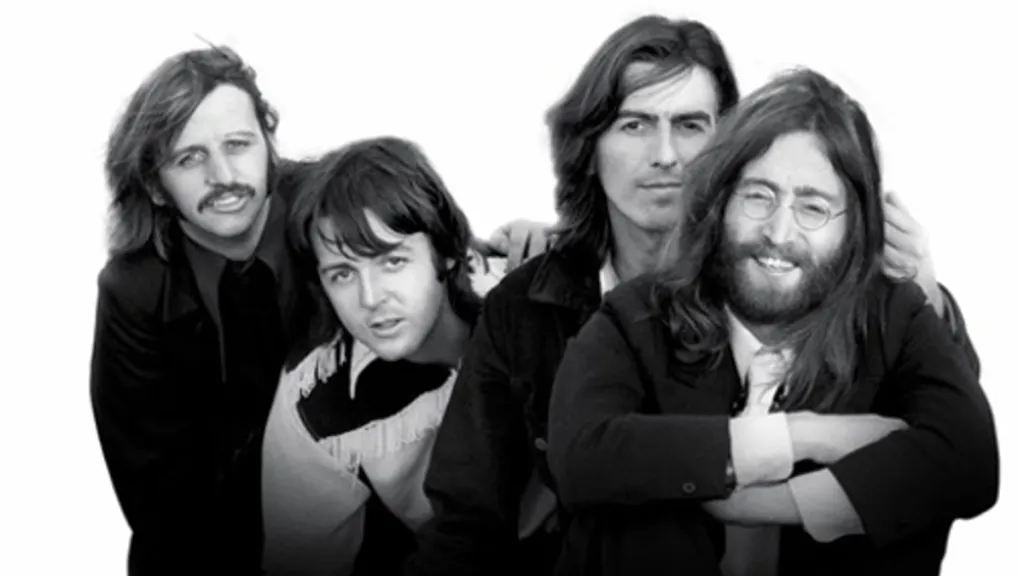

The Beatles Anthology 2025

I recently finished watching the 30th-anniversary edition of The Beatles Anthology, released in 2025. Having never seen the original 1995 broadcast, I went into this definitive series with a completely fresh perspective. This updated version, beautifully restored and now featuring a brand-new ninth episode, remains the gold standard for deep dives into the world’s most influential band. It is a staggering piece of filmmaking that traces the Fab Four's journey from the sweat-soaked walls of Liverpool’s Cavern Club to the rooftop of Savile Row, telling a story that feels as vital today as it did three decades ago.

What makes this edition particularly special is the inclusion of that ninth chapter, which expands on the original eight-part series. It offers a poignant look at previously unseen footage of Paul, George, and Ringo reunited in the mid-90s, capturing the raw chemistry and reflection that occurred when they first sat down to tell their own story.

After spending hours immersed in their world, I left the series with some overriding thoughts.

Four Lads from Liverpool

The Beatles have been placed on a mantle virtually alone compared with other musicians.

Humanising the Icons: Humour and Grit

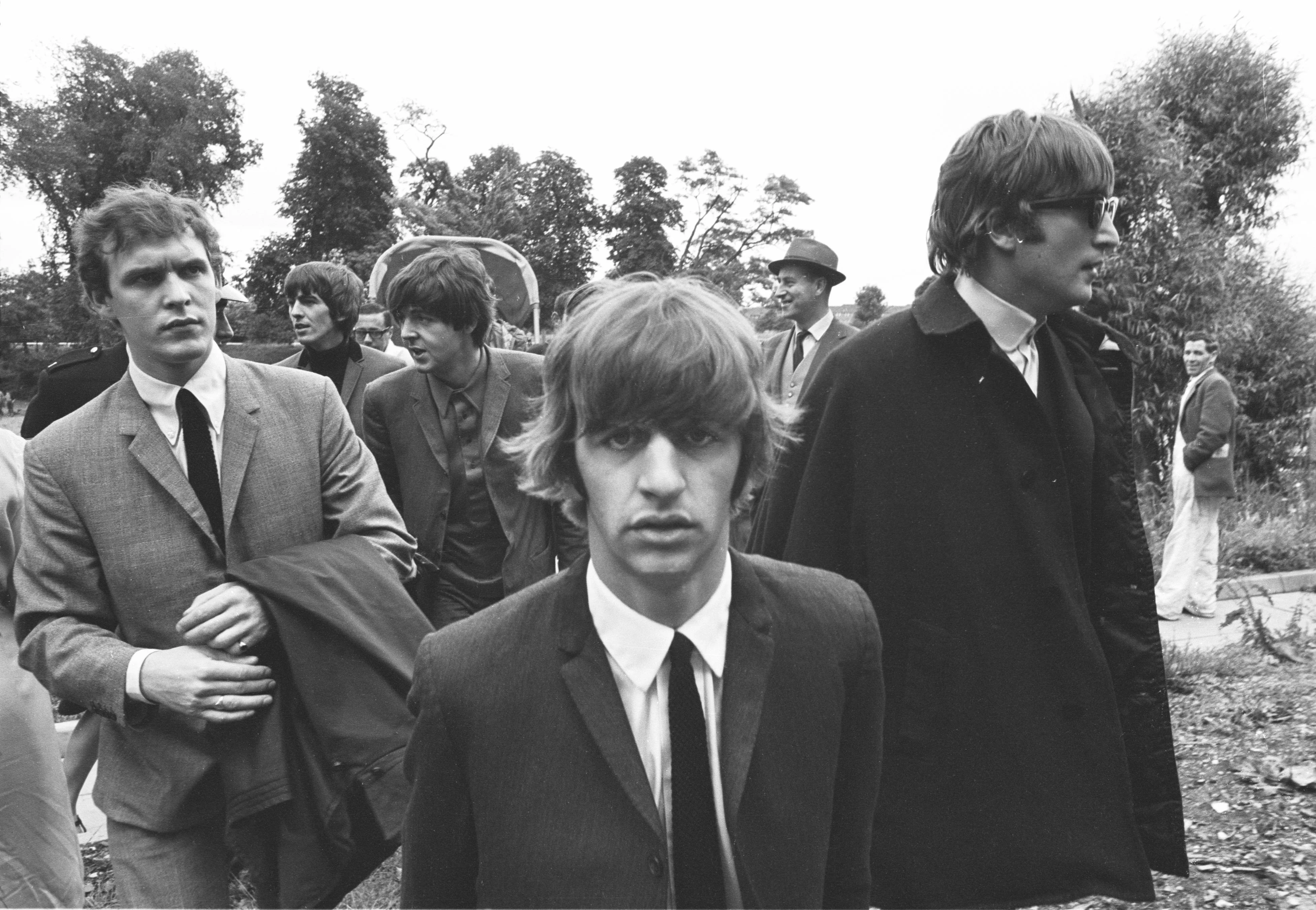

What they did in eight years together was exceptional; however, when watching the footage in Anthology, the one thing that hits you straight away in all of the interviews is just how normal they were.

George Harrison, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr were interviewed specifically for 'Anthology', and because it was released fifteen years after the tragic death of John Lennon, they piece together his contributions through archive footage.

The band, all four of them, come across as really human across all of the episodes. Talking about the early days in the Cavern Club and Hamburg. To George and Ringo, forgetting that the band played Shea Stadium twice. The grandiose nature of what they did not once bother them. One thing that really stuck with me is just how funny they all were.

In one episode, the band are on the Morecambe and Wise show, and all four members are seen having a joke with the two presenters, and all of them are as funny as each other. There's also a rawness and a grit to them. For example, snubbing President Marcos' invitation to dinner in Manila, and Paul McCartney telling a journalist truthfully that he'd taken LSD and then stating to the same journalist, "it's his responsibility, you know, for spreading it, not mine".

Genuine Moments: Old Wounds and Friendships

The story is amazing. It's told from the mouths of four ordinary men who did something extraordinary. What the Beatles did, the world had never seen before, and we will never see again. It doesn't feel like a recount either; there are genuine moments of friendship, and the old wounds haven't gone away. Harrison dismisses the Apple farrago as “John and Paul’s egos running away with them”. McCartney still sounds annoyed that Lennon got to ride in a helicopter with the Maharishi. Ringo has a brief moment where he compliments George as a songwriter in one episode and mentions how hard it must have been for him to take songs to Lennon and McCartney.

The three songwriters all give their opinions on The Beatles. Lennon put it, “Nothing will ever break the love we had for each other.” McCartney called them "a great little band." Harrison, meanwhile, said, "The Beatles exist without us; it will go on in people's memories and minds"

They Changed the World

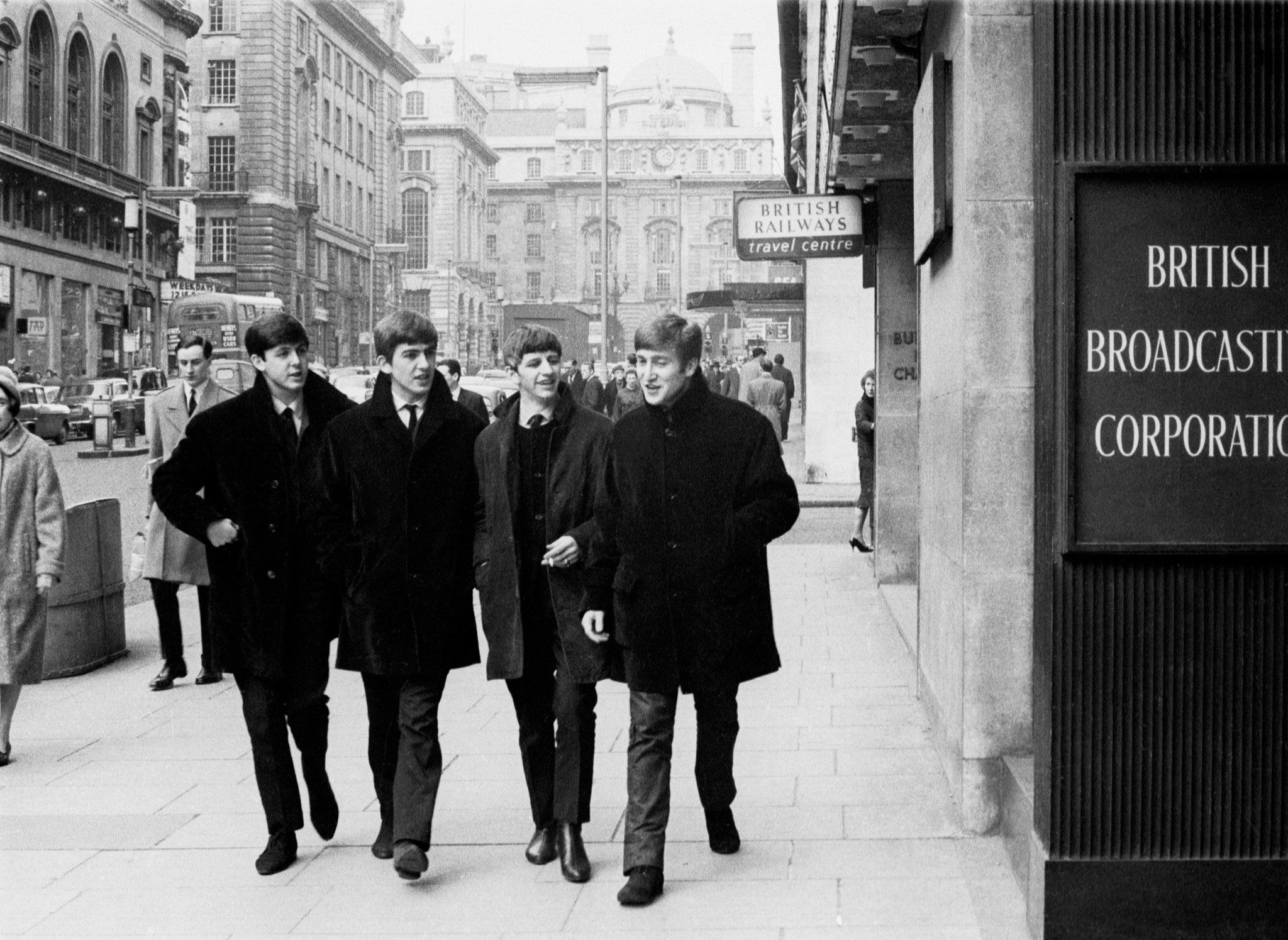

The First Global Superstars: From the Cavern to Stadiums

In Anthology, you really get a perspective for just how big The Beatles were, and a snapshot into Beatlemania. When the band first arrived in New York in 1964, the footage is extraordinary; thousands of adoring fans meet them, and it doesn't let up. All of the members commented that they were mobbed everywhere they went. Harrison joked that the only peace he could find was in the bathroom of hotel rooms.

Whilst this was happening, though, the Beatles were still only in their twenties; they wanted to meet Elvis, and here they were being portrayed as the next big thing. They were the first global superstars. Elvis had never been to Europe or England. The Beatles' going to America was a big deal.

They were huge in the UK too; it seemed that every release would chart and chart well. Adoring fans were part and parcel of The Beatles' package; it happened all over the world.

As musicians, they were the first to do what they did; artists and bands didn't tour the world as they did. The Beatles played across America, Australia, Japan, the Philippines, Europe and the UK, and they stopped touring halfway through their tenure.

Watching the updated footage of Shea Stadium and Candlestick Park. Now remastered using Peter Jackson's AI, you get a perspective on the scale of The Beatles. They were the first stadium band, and you also quickly find out why they stopped playing live. Screaming fans meant that the band couldn't hear each other on stage. As fans throw bodies at them, as if they were some sort of musical god sent to them from the heavens.

Spiked Tea and Spiritual Shifts: The Counter-Culture Influence

There are also a lot of moments when the band understood what was going on around them. Drugs are spoken about openly; all four members, on separate occasions, admit to taking LSD, uppers and smoking marijuana. 'Revolver' and 'Sgt Pepper's' weren't made on cups of tea, were they?

However, there's a real openness when talking about them. In one episode, George mentions the first time he and John took it, when they were spiked by their dentist, John Riley, during a dinner party. He later mentions that when he headed to America, at the height of the summer of love, expecting to find a load of young creatives changing the world, and what he actually found was a load of strung-out kids, addicted to acid. His perspective on the drug quickly changed, and he would move on to exploring mediation and subsequently meet the Maharishi.

When the band was performing on the world's first ever satellite broadcast around the world, they took the moment to sing 'All You Need is Love'.

They would set up their own label, 'Apple Records', which originally aimed to provide a platform for upcoming musicians and artists. It could be argued that the Beatles set up the first indie label, a trend which would continue into the 70s and 80s.

The Studio as an Instrument: Redefining the Pop Song

Once the band had given up playing live in 1966, following the show at San Francisco's Candlestick Park. They would focus on creating new, interesting music in the studio. In a short amount of time, they'd evolved from the four mop tops from Liverpool singing 'Help' and 'All My Loving' into timeless songwriters. 'Rubber Soul' marked Lennon and McCartney as a tour de force of songwriting. 'In My Life' and 'Nowhere Man' are exceptional records, and they proved that The Beatles were moving away from the live setting.

By the time of 'Revolver' alongside George Martin, The Beatles were creating masterpieces. McCartney had 'Eleanor Rigby', a song that was unlike anything they'd recorded or released before, built around piano and strings rather than two guitars, bass and drums, which had been the cornerstone of the band's sound until that point. George Harrison would show his songwriting prowess with 'Taxman', an attack on the establishment 11 years before punk, with a bassline that would influence a certain Paul Weller and Ian Brown to write their own scathing efforts years later.

Tomorrow Never Knows': The Blueprint for Modern Music

Lennon's 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was the moment, though. Lennon wrote a song based on a book he'd been reading, 'The Psychedelic Experience,' a 1964 book written by Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert, which contained an adaptation of the ancient 'Tibetan Book of the Dead'.

The origins of most modern popular music, with the exception of rap, can be traced directly back to The Beatles’ catalogue; of all their innovations, none was more groundbreaking than 'Tomorrow Never Knows.’ Written in 1966 at the height of their creative restlessness, it stands as their most radical and influential track. The result was more than just the apex of psychedelia. It was the moment a mainstream pop audience first encountered both Eastern spiritual philosophy and music as a tool for expanded consciousness. In reshaping the very concept of what a pop song could be, The Beatles inadvertently sketched out the blueprints for entire genres to come. Even today, the track is routinely cited as a cornerstone of modern production, its DNA woven through countless strands of contemporary music.

The Beatles then set about recording some of their best work. 'Sgt Peper's Lonely Hearts Club Band' saw the band become a fake group, Lennon and McCartney combining songs to create 'A Day in the Life'. A song that saw the everyday made epic. Lennon’s ‘Sgt. Pepper…’ closer viewed a series of newspaper articles: about the death of Guinness heir Tara Browne and road repairs in Lancashire, through LSD specs and came out with a world-beating vision. Includes arguably the most famous crescendo in rock.

George's songwriting came to further fruition; his Indian influences came through on 'Love You To' and 'Within You Without You', both featuring him on the Sitar. Later in the band's career, he'd contribute 'While MY Guitar Gently Weeps', 'Something' and 'Here Comes the Sun'

Sonic Alchemists: Varispeed, Tape Loops, and the Moog

They would effectively invent heavy metal with 'Helter Skelter'; become the first band to use backwards guitars and vocals on 'Rain' and 'Paperback Writer'; introduce intentional guitar feedback on 'I Feel Fine'; and pioneer automatic double-tracking on 'Tomorrow Never Knows'.

They also pushed studio experimentation through tape manipulation techniques such as varispeed, altering tape speed during recording or mixing to change both pitch and tempo simultaneously, producing heavier, dreamlike, or sped-up, cartoonish effects. This can be heard on the slowed-down recording of 'Rain', as well as in the splicing together of two takes recorded at different speeds for 'Strawberry Fields Forever'.

Further innovations included the use of tape loops, which created repetitive, found-sound textures by physically splicing loops of magnetic tape and feeding them back through the recording machine. They were also among the first bands to use a Moog modular synthesiser on a major release, incorporating it during the recording of 'Abbey Road', most notably on 'Here Comes the Sun' and 'Because'.

Even the so-called weaker tracks on albums, i.e. 'Yellow Submarine', have a charm, and a place within the band's catalogue. What they did at this time is truly special.

The Magnificent Seven

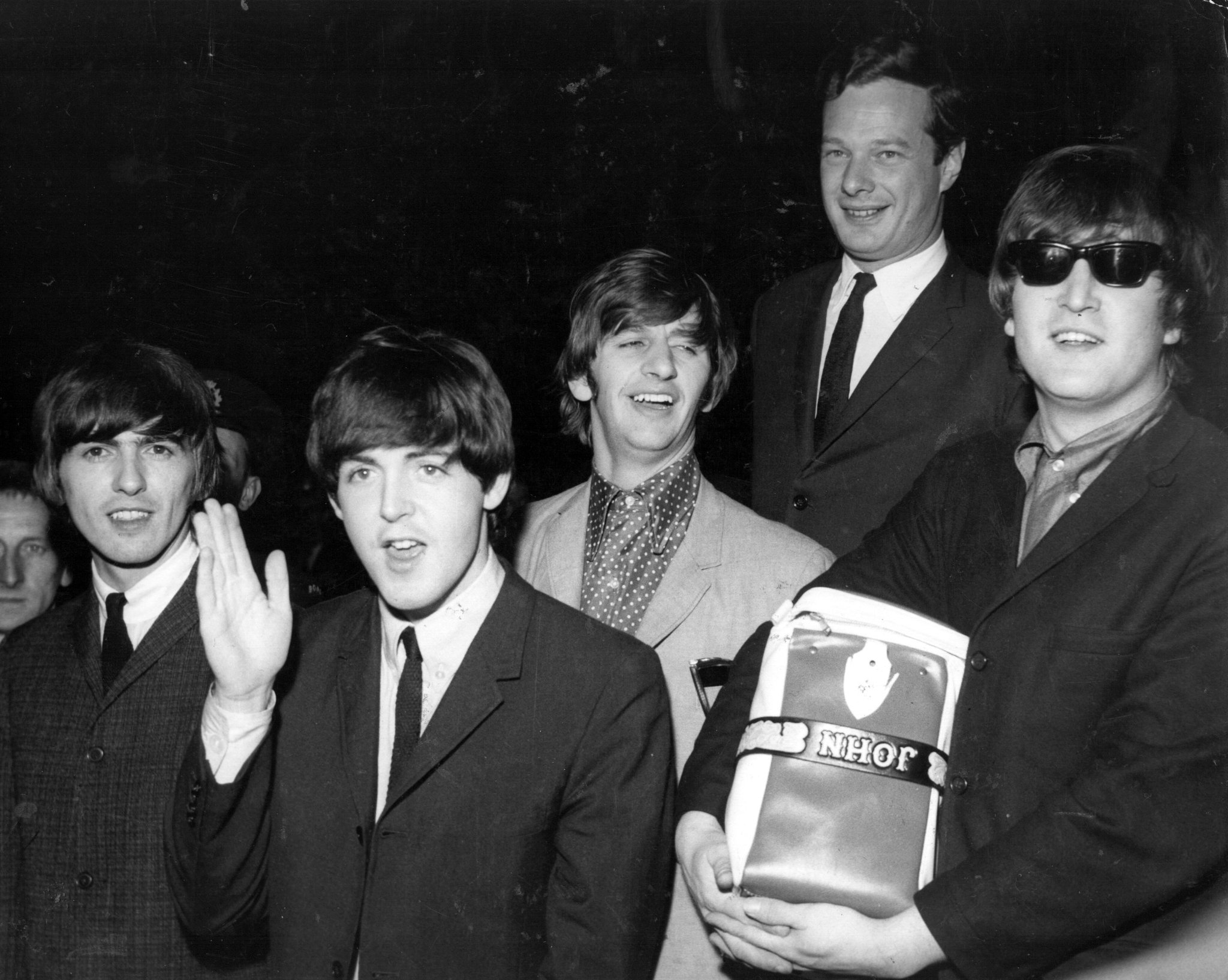

The Beatles are often referred to as the 'Fab Four', that four being John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. However, there are three more important people in the Beatles' story. Brian Epstein, George Martin, and Neil Aspinall.

Brian Epstein: The Architect of the Image

Brian Epstein was the band's manager, originally running a music store named NEMS. Before spotting The Beatles in November 1961. Epstein would manage the band until his death in August 1967, aged 32. His death was officially ruled an accidental overdose of a combination of alcohol and barbiturates

The Beatles themselves were away in Bangor, North Wales, with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi when they received the news. None of the band members attended his funeral to avoid unnecessary media attention. John Lennon is quoted as saying that Brian's death was where it "started to all fall apart" for the band.

After Epstein's death, The Beatles' story would change forever. It arguably marked the beginning of the end for the band. In 'Anthology', there is some truly harrowing footage of the band, in particular John Lennon and George Harrison, being interviewed by the press just a few minutes after finding out that Epstein had passed. It's quite mad to see the band trying to come to terms with what they've just been told whilst being questioned by the world's press.

Epstein was so much more to The Beatles than a manager; he'd been the one who first spotted them, he acted as a mentor, and was the one who managed the band's business interests and itinerary. In Anthology, it's the first time we see the vulnerable side of the band; there is a period where they all become quite lost.

The band understood the importance of Epstein in their story. McCartney summarised the importance of Epstein when he was interviewed in 1997 for a BBC documentary about Epstein, saying: "If anyone was the Fifth Beatle, it was Brian." In his 1970 Rolling Stone interview, Lennon commented that Epstein's death marked the beginning of the end for the group: "I knew that we were in trouble then ... I thought, 'We've fucking had it now.'"

Following his death, The Beatles would have to navigate these new challenges themselves. No longer just the four mop tops from Liverpool, they were seen as the biggest band in the world and spokespeople of a generation.

Neil Aspinall: The Keeper of the Flame

Helping them work through these challenges would be Neil Aspinall. Originally employed as their first road manager, after the appointment of Mal Evans, Apinall became their personal assistant and would later become chief executive of their company, Apple Corps.

Following the death of Epstein in August 1967, there was a vacuum in the management of the Beatles' affairs. The Beatles asked Aspinall to take over the management of Apple Corps in 1968, which had been founded in April of the same year. Aspinall later said that he only accepted the position after being asked, but did not want to do it full-time, and would only do it "until they found somebody else."

Aspinall later spoke of the Beatles' business arrangements: We did not have one single piece of paper. No contracts. The lawyer, the accountants and Brian, whoever, had that. The Beatles had been given copies of various contracts, maybe, I don't know. I didn't know what the [recording] contract was with EMI, or with the film people or the publishers or anything at all. So it was a case of building up a filing system, finding out what was going on while we were trying to continue doing something.

Aspinall was there for it all; his voice is one of the most prominent in 'Anthology', discussing everything from the band's live shows to the relationships between the four. He was as much of a part of the magical circle that was The Beatles as anyone else. He was with them through all their years of fame. He would get shouted at, told to fetch impossible things, and fix ludicrous arrangements. But Neil was more than a roadie and fixer, he was their friend and confidant, helped with words of songs when they got stuck, with personal relationships when they wanted them unstuck.

His accountancy training proved invaluable when he came to run Apple. As the years went on, he masterminded much of the group's professional affairs and back catalogues. On the whole, Neil won most of the battles, helping them make further millions. He also had a creative streak, acting as the producer of the film Let It Be and organising the Beatles 'Anthology'.

It was his idea for the band to tell the story that everyone else from that time had attempted to tell.

This may seem hard to believe, but by the 1980s and 1990s, The Beatles’ reputation and cultural standing had begun to waver. John Lennon had been shot dead by Mark Chapman outside his New York home in 1980, and the surviving Beatles were each experiencing uneven periods in their careers. Paul McCartney endured a run of creative misfires, including ‘Give My Regards to Broad Street’ and ‘The Frog Chorus’. Ringo Starr was battling alcoholism, while George Harrison had turned his attention to the supergroup The Travelling Wilburys.

In 1992, Apple Corps revisited an abandoned documentary project from 1971 titled ‘The Long and Winding Road’. Originally conceived as a 90-minute film compiled by Apple manager and longtime confidant Neil Aspinall, it drew on interviews, concert footage, and television appearances, though notably without direct participation from the band themselves. Just days before his death in 1980, Lennon had reportedly expressed renewed enthusiasm for the project, even imagining a reunion concert as its climactic finale. His murder by Mark Chapman tragically brought those plans to an end, and the film was once again shelved.

A decade later, McCartney, Harrison, Starr, press officer Derek Taylor, and producer George Martin agreed to resurrect it, with Jools Holland conducting new interviews alongside archive footage of Lennon. Retitled ‘The Beatles Anthology’.

The Anthology project evolved into a full multimedia event: three double albums accompanied the documentary between late 1995 and early 1996, with a companion book following four years later. Across six CDs, fans discovered alternate takes, unreleased tracks, and snippets of studio chatter spanning the band’s entire recording career.

Aspinall, in particular, played a huge part in getting the footage, both video and audio, together for the project. It was his aim for The Beatles to tell their story in their own words.

George Martin: The Master of the Impossible

Finally, The Beatles don't sound like they do without the skills of one man. George Martin. The identity of the true “fifth Beatle” has been hotly debated for half a century, but the strongest case can be made for Sir George Martin. The band’s trusted and loyal producer, Martin, served as expert and conspirator, taskmaster and mad scientist, friend and father figure throughout the band’s studio life. He shaped their songs in ways that are seldom appreciated but impossible to forget.

Unlike most producers of his era, his creative daring fostered an environment where it was acceptable to explore and expand the realm of the possible. He played with the Beatles, in every sense of the word, by picking up an instrument, or merely indulging their curiosity and translating their abstract musical fantasies into reality. “He was always there for us to interpret our strangeness,” recalled George Harrison. It’s difficult and frightening to imagine the Beatles’ artistic trajectory had they been paired with anyone else. His role as a confidant, advocate and realiser cannot be overstated.

George Martin worked with The Beatles throughout their entire recording career, producing them from their very first single, ‘Love Me Do’. His influence was immediate and decisive: it was Martin who advised Lennon and McCartney to speed up ‘Please Please Me’, then famously declared upon hearing the finished recording, “Gentlemen, you have just made your first Number One record.”

He encouraged McCartney to record ‘Yesterday’ despite the rest of the band being unsure what to do with it. He added the baroque piano solo to ‘In My Life’ while the band stepped out for a cup of tea. His innovations are everywhere: the pioneering use of echo on ‘And I Love Her’; the explosive opening chord of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’; the apocalyptic final chord of ‘A Day In The Life’; the piccolo trumpet on ‘Penny Lane’; the stark, Hitchcock-influenced string score of ‘Eleanor Rigby’; the gloriously unhinged backing track of ‘I Am The Walrus’; and the meticulous reconstruction of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ from its authors’ abstract ideas.

For ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite!’, Martin recorded a variety of fairground organs, sliced the tapes into fragments, and randomly reassembled them. The result was a dizzying, disorienting swirl, a kind of demonic carousel.

His work on ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, however, stands as his magnum opus; even today, it's nothing short of extraordinary.

The Beatles devoted more studio time to Lennon’s hallucinatory new song than almost any track they had recorded to that point, burning through 55 hours of tape as they attempted take after take. Eventually, the song existed in two distinct versions: one fast and forceful, bolstered by Martin’s dramatic orchestral arrangement, and another slower, gentler, and dreamlike. Lennon loved the hushed opening of the latter and the raucous ending of the former and found himself unable to choose.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you join the beginning of the first one to the end of the second one?’” Martin later recalled. “‘There are two things against it,’ I replied. ‘They’re in different keys and different tempos.’” While trivial to fix today, this posed a formidable challenge in the analogue age. Lennon, unfazed, simply replied: “Well, you can fix it!”

Armed with little more than two tape machines and a pair of scissors, Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick performed a minor mechanical miracle, altering the speed of both recordings and physically splicing the tapes together at the one-minute mark. Fix it, he did.

George Martin’s contribution to The Beatles cannot be overstated. Without him, many of their ideas would never have fully come to life. He was the ideal guide, encouraging Lennon’s wild imagination, pushing McCartney to keep writing, and embracing stylistic departures far beyond traditional rock ’n’ roll. ‘Yesterday’ marked the first time rock and pop were fused so seamlessly with classical music. With Harrison, Martin helped translate Eastern philosophy and Indian musical influences into Western pop, most notably on ‘Love You To’ and ‘Within You Without You’.

Martin’s contributions to The Beatles’ legacy are rich and varied, consistently positive and often astonishing. He took great songs and made them even greater.

It is often said that when the doors to Studio Two at Abbey Road closed, the pressures of Beatlemania were temporarily left outside. Yet Martin offered something even more enduring. He holidayed with Lennon and his first wife Cynthia, travelled to America with the band on their groundbreaking early visits, remained carefully aloof during their flirtations with harder drugs, introduced McCartney to classical music and as a family man, a “grown-up” and a “real musician”, as they affectionately called him served as a steady, calming presence amid the relentless whirlwind of their expanding world.

His contributions to the Anthology documentary are equally remarkable. Martin speaks with rare clarity and humility about his creative input, carefully balancing technical insight with genuine affection for the band. More than simply recounting studio decisions, he offers a window into the relationships he shared with each of the four Beatles, understanding Lennon’s volatility and wit, nurturing McCartney’s discipline and melodic ambition, supporting Harrison’s growing confidence, and quietly steadying Starr’s often-overlooked musical instincts. Throughout Anthology, he emerges not just as their producer, but as a trusted confidant, mediator, and surrogate fifth Beatle, someone who understood both the music and the men behind it.

Good from the Get Go

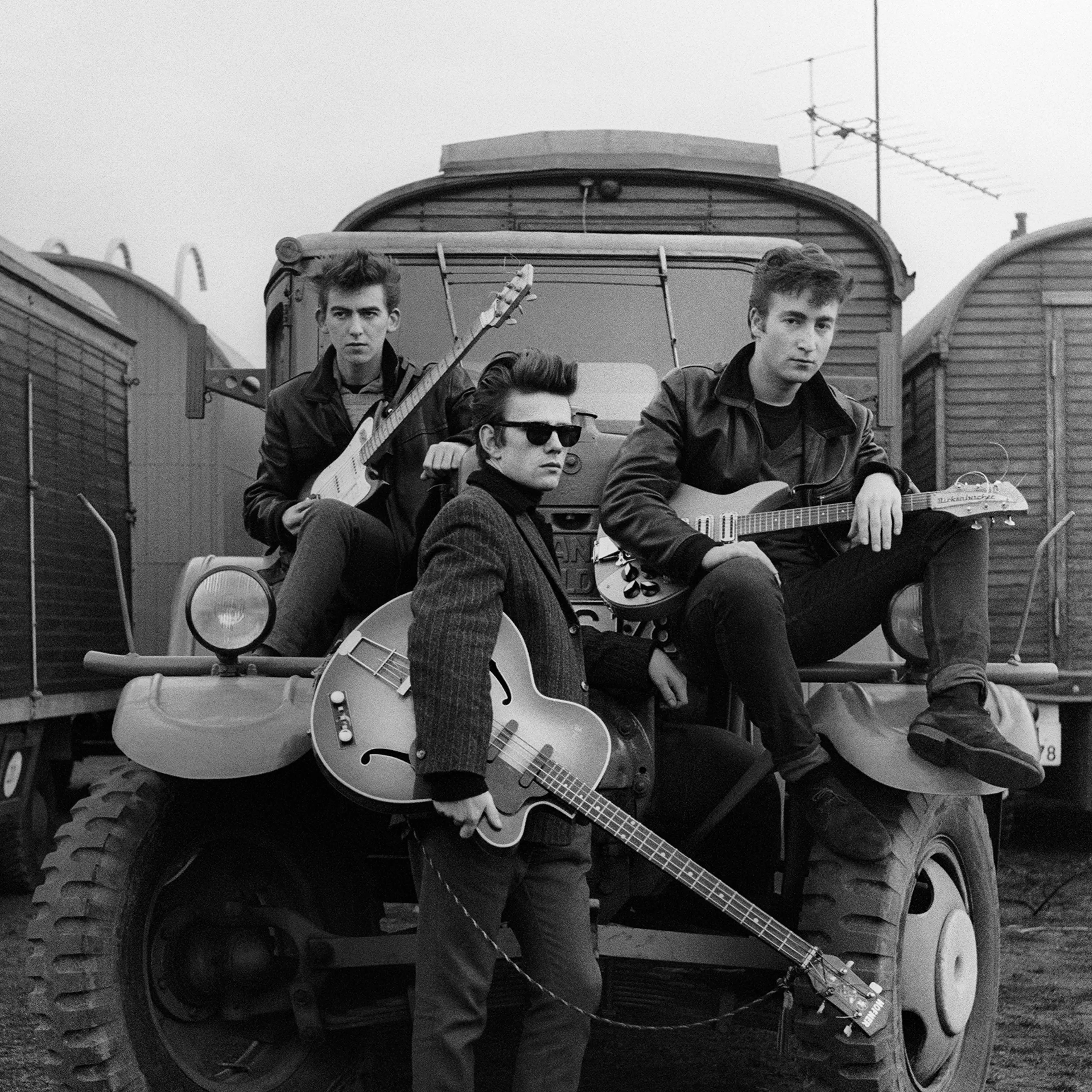

The Beatles' story lasts around ten years in total, and they picked up being good musicians pretty quickly. In November 1956, sixteen-year-old John Lennon formed a skiffle group with several friends from Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool. They were called the Quarrymen, a reference to their school song "Quarry men old before our birth". Fifteen-year-old Paul McCartney met Lennon on 6 July 1957 and joined as a rhythm guitarist shortly after.

Lennon and McCartney had been playing together for a few months before Harrison joined the band after he performed the lead guitar part of the instrumental song 'Raunchy' on the upper deck of a Liverpool bus. By January 1959, Lennon's Quarry Bank friends had left the group, and he began his studies at the Liverpool College of Art. Lennon's art school friend Stuart Sutcliffe, who had just sold one of his paintings and was persuaded to purchase a bass guitar with the proceeds, joined in January 1960.

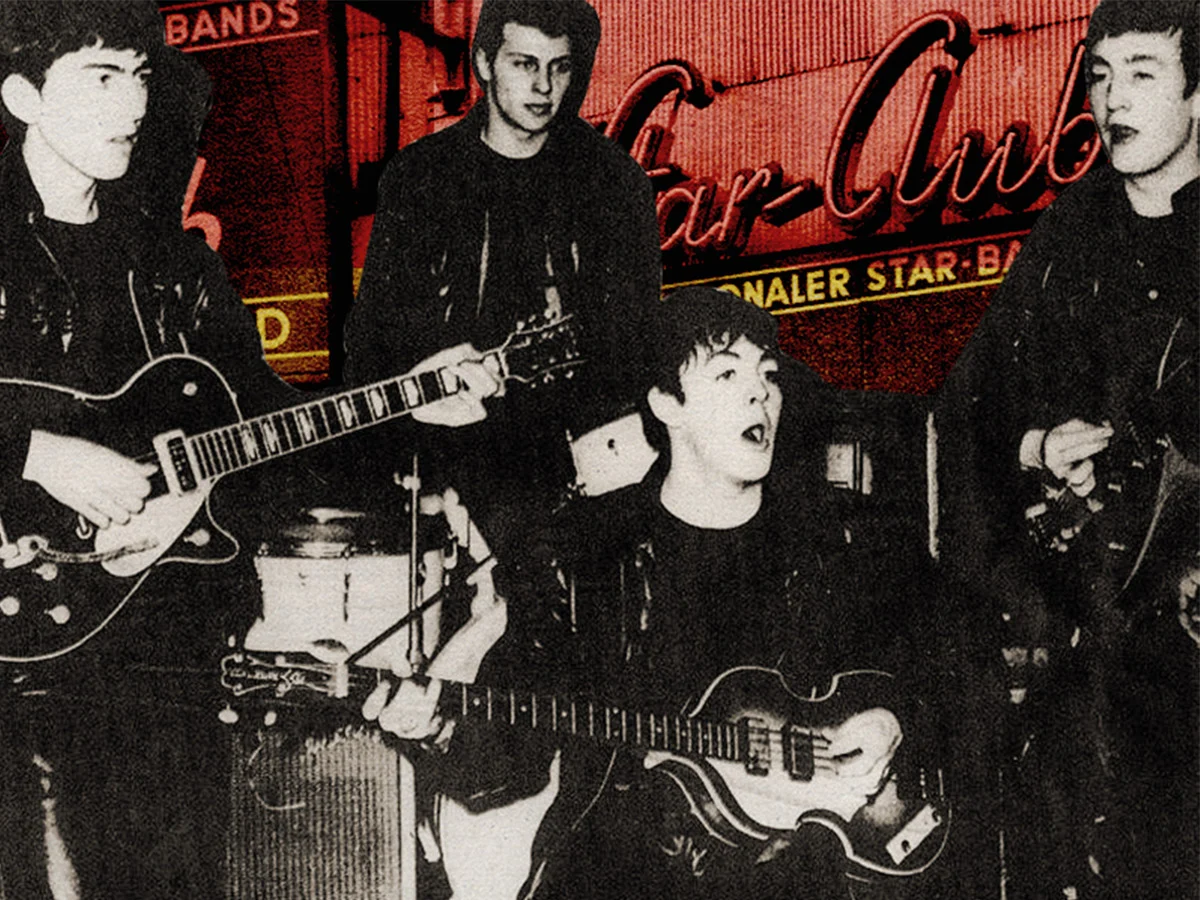

The Hamburg Apprenticeship: 800 Hours of Rock n' Roll

Allan Williams, the Beatles' unofficial manager, arranged a residency for them in Hamburg. They auditioned and hired drummer Pete Best in mid-August 1960. The band, now a five-piece, departed Liverpool for Hamburg four days later, contracted to club owner Bruno Koschmider for what would be a 3+1⁄2-month residency.

Hamburg is where The Beatles would first get to see the wonders of sex, drugs and rock n roll. Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn writes: "They pulled into Hamburg at dusk on 17 August, the time when the red-light area comes to life ... flashing neon lights screamed out the various entertainment on offer, while scantily clad women sat unabashed in shop windows waiting for business opportunities.

It was also where they'd learn their trade as musicians. Homing their songcraft and live performances.

McCartney would later describe the band’s experience in Hamburg as “800 hours in the rehearsal room”. The intensity of their workload bred a need for artificial stimulants, and it wasn’t long before The Beatles were popping amphetamines on a nightly basis, with some (i.e. Lennon) taking more than others. “The waiters always had these pills [Preludin], so when they saw the musicians falling over with tiredness or drink, they’d give you the pill,” McCartney later said of his first experience of ‘prellies’. “You could work almost endlessly until the pill wore off, and then you’d have another.”

The band’s regular seven-hour sets meant there was a near-constant need for new material. This engendered a strong work ethic that would stay with the band until their dissolution. New songs were being written every day, allowing the band to finesse and experiment with their sound and expand their setlist. “We had to play for hours and hours on end,” Lennon said of that time. “Every song lasted twenty minutes and had twenty solos in it. That’s what improved the playing. There was nobody to copy from.

Sutcliffe would leave the band, and McCartney would become the bass player. After the Beatles completed their second Hamburg residency, they enjoyed increasing popularity in Liverpool with the growing Merseybeat movement. However, they were growing tired of the monotony of numerous appearances at the same clubs night after night. In November 1961, during one of the group's frequent performances at the Cavern Club, they encountered Brian Epstein, a local record-store owner and music columnist.

Marred in Tragedy

The Beatles' story has everything. However, three of the most significant events in the band's story are three deaths. I've mentioned the death of Brian Epstein above, who passed away aged 32 in 1967, after managing the band for 6 years.

Stuart Sutcliffe: The "Lost" Beatle

Stuart Sutcliffe would also pass away, not long after leaving The Beatles. In July 1961, Sutcliffe decided to leave the group to continue painting. After being awarded a postgraduate scholarship. He enrolled at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg, where he studied under the tutelage of Eduardo Paolozzi.

While studying in Germany, Sutcliffe began experiencing severe headaches and acute sensitivity to light. In February 1962, Sutcliffe collapsed during an art class in Hamburg. Kirchherr's mother had German doctors examine him, but they were unable to determine the exact cause of his headaches. They suggested he return to the UK and have himself admitted to a hospital with better facilities; however, after arriving, Sutcliffe was told nothing was wrong and returned to Hamburg. He continued living with his girlfriend's family, but his condition soon worsened. After he collapsed again on 10 April 1962, Astrid Kirchher, his girlfriend, took him to the hospital, riding with him in the ambulance, but he died before they arrived. The cause of death was a cerebral haemorrhage, specifically a ruptured aneurysm. This resulted in cerebral paralysis due to severe bleeding into the right ventricle of the brain. He was 21 years old.

On 13 April 1962, Kirchherr met the Beatles at Hamburg Airport, telling them Sutcliffe had died a few days earlier. Sutcliffe's mother flew to Hamburg with Beatles manager Brian Epstein and returned to Liverpool with her son's body. Sutcliffe's father did not hear of Stuart's death for three weeks, as he was sailing to South America on a cruise ship, although the family arranged for a padre, a military chaplain, to give him the news as soon as the ship docked in Buenos Aires.

Although Lennon did not attend or send flowers to Sutcliffe's funeral, his second wife, Yoko Ono, recalled that Lennon mentioned Sutcliffe's name often, saying he was "[My] alter ego ... a spirit in his world ... a guiding force".

The Beatles' compilation album Anthology 1, released in 1995, had previously unreleased recordings from the group's early years. Sutcliffe plays bass with the Beatles on three songs they recorded in 1960: 'Hallelujah, I Love Her So', 'You'll Be Mine', and 'Cayenne'. In addition, he is pictured on the front covers of all three Anthology albums. As well as being featured on the band's 1967 album 'Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'.

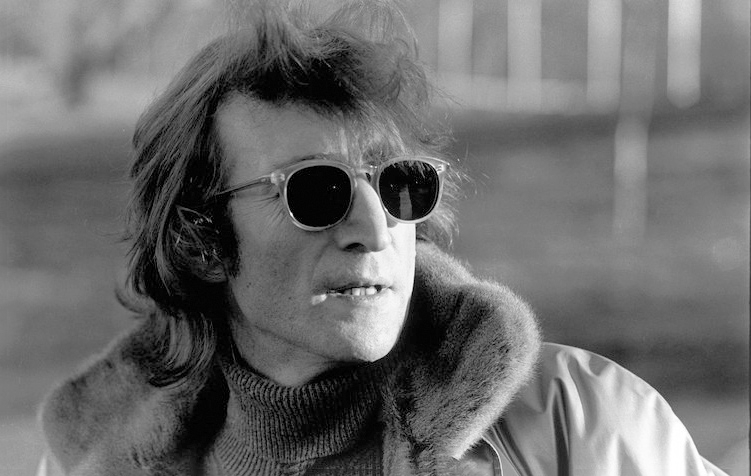

The Death of John Lennon: A World in Shock

John Lennon's death happened ten years after The Beatles broke up. On December 8th 1980, Lennon was shot dead outside the Dakota Building in New York by Mark Chapman.

Mark David Chapman, an American fan of The Beatles, harboured envy and resentment toward Lennon, fuelled by the singer’s lifestyle and his 1966 comment that The Beatles were "more popular than Jesus." Chapman claimed he was inspired by Holden Caulfield, the protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye. Caulfield, often described as a 'phoney-killer', despised hypocrisy. A sentiment Chapman disturbingly identified with.

Chapman planned the killing over several months and waited for Lennon at the Dakota on the morning of December 8, 1980. Early in the evening, Chapman approached Lennon, who graciously signed a copy of his album 'Double Fantasy' before heading to a recording session at the Record Plant. Later that night, Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, returned to the Dakota to say goodnight to their son before heading out for an impromptu date night.

As Lennon and Ono approached the building’s entrance, Chapman fired five hollow-point bullets from a .38 Special revolver, four of which struck Lennon in the back. Lennon was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital in a police car, where he was pronounced dead on arrival at 11:15 p.m. He was just 40 years old.

Chapman remained at the scene, reading The Catcher in the Rye, until he was arrested by the police. Investigations later revealed that Chapman had considered targeting other celebrities, including David Bowie.

The news of Lennon’s murder sent shockwaves through the world of music and popular culture. While Lennon was best known as a member of the biggest band in the world, The Beatles, he was much more than that: a political activist, a father, a husband, and an extraordinary songwriter.

The Great "What If": A Reunion in Full

I honestly believe that, despite the bad blood that existed between the members of The Beatles, they would have eventually resurrected their relationships. By the late 1970s, the ice had already started to thaw; we know that Lennon and McCartney had begun meeting up again at the Dakota in New York, moving past the legal battles and back toward a private friendship.

We know that in 1995, the surviving Beatles reconvened to record new music and to make Anthology, but it’s impossible not to wonder what would have happened had John still been alive. The tragedy of 1980 didn't just rob the world of a visionary artist; it robbed the band of a true, four-way resolution.

Instead of George, Paul, and Ringo huddling around a lo-fi cassette of 'Free as a Bird' working with the "ghost" of John’s voice, we might have seen all four of them in a room together. They would have likely been bickering and laughing in equal measure, but creating with that same telepathic chemistry they possessed at Abbey Road. While the "Threetles" did a beautiful job honouring John’s demos, there is an undeniable melancholy to the Anthology footage of them playing along to a tape.

A living John Lennon would have brought that missing edge, the sharp cynic, to Paul’s bright optimist. While we will never know what a 1995 Lennon/McCartney composition would have sounded like, the Anthology serves as a bittersweet reminder that even in his absence, John remained the heartbeat of the band.

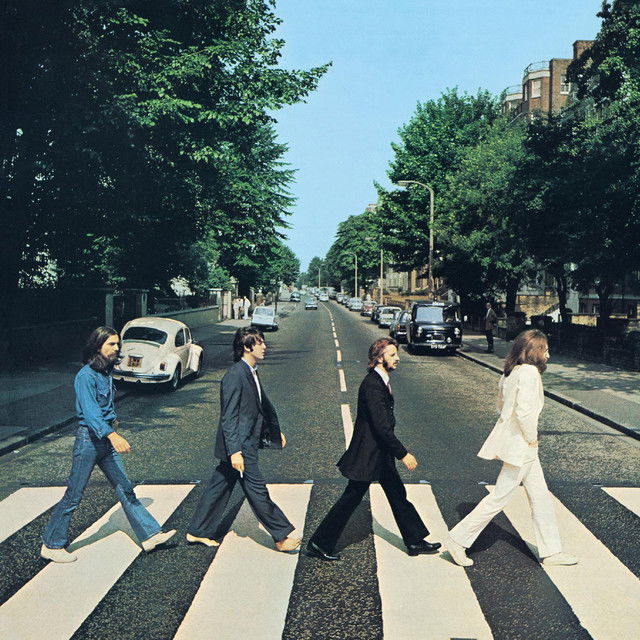

They Ended on a High

The last album officially released by them is the 1970s 'Let It Be'. However, the last thing the band would record would be 'Abbey Road'. The songs for 'Let It Be' were recorded earlier in 1969, for the failed TV Special. An idea attributed to McCartney, who suggested they "record an album of new material and rehearse it, then perform it before a live audience for the very first time on record and on film. Originally intended for a one-hour television programme to be called Beatles at Work, in the event, much of the album's content came from studio work beginning in January 1969, many hours of which were captured on film by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg. This footage would become available to fans in 2021's 'Get Back'.

The Winter of Discontent: The 'Get Back' Sessions

Martin said that the project was "not at all a happy recording experience. It was a time when relations between the Beatles were at their lowest ebb. Lennon described the largely impromptu sessions as 'hell ... the most miserable ... on Earth', and Harrison, "the low of all-time"

Originally, plans for live performances were for the band to play on a boat at sea, in a lunatic asylum, the Libyan desert and the Colosseum. Ultimately, what would be their final live performance was filmed on the rooftop of the Apple Corps building at 3 Savile Row, London, on 30 January 1969.

Financial and personal strains began to erupt, with The Beatles disagreeing on potential managers and business interests for the band. Many saw it as the beginning of the end.

However, they felt a pull to return to the studio one last time, and once again approached George Martin. He later admitted that he was surprised when McCartney asked him to produce another album; the 'Get Back' sessions had been, in his words, “a miserable experience”, and he had “thought it was the end of the road for all of us”.

One Last Time: Discipline and the Return of George Martin

Martin agreed but only on one condition: that they work as they always had before, with discipline, structure, and a shared commitment to the craft of recording. Remarkably, they rose to the challenge. The result was ‘Abbey Road’, a record that stands as one of the most elegant and assured farewells in popular music.

The album captured each Beatle at a distinct creative peak. McCartney provided polish and melody in ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’, ‘Oh! Darling’, and the grand architectural sweep of the side-two medley. Lennon contributed some of his heaviest and most visceral work, particularly ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, a song whose relentless intensity and abrupt ending felt like a full stop on an era already nearing its conclusion.

The Harrison Ascent: 'Something' and 'Here Comes the Sun

Most striking of all was George Harrison’s emergence. Long constrained by the Lennon–McCartney partnership, he delivered two of the finest songs of the band’s entire career: ‘Something’, a tender, aching love song that Frank Sinatra would later call “the greatest love song of the last fifty years”, and ‘Here Comes the Sun’, radiant and hopeful, written during a brief escape from band tensions. Together, they announced Harrison not as a junior partner, but as a songwriter fully equal to his peers.

On 20 August 1969, the four Beatles were in the studio together for the final time, recording the last elements of Lennon’s ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’. Within weeks, the group would quietly drift apart, though none of them yet knew it was truly the end.

The End: A Love Letter to the World

Yet ‘Abbey Road’ feels deliberately conclusive. From its immaculate production to its carefully sequenced final moments, it plays like a farewell made in full awareness. It is fitting, then, that the last words ever sung by The Beatles together are not bitter or unresolved, but generous and profound: “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

The album is often considered one of the band's greatest achievements, their love letter to the world and each other.

I implore you to watch 'Anthology'. It tells the story of the most important band ever, four lads from Liverpool who changed the world. What they did will never be repeated. Not because music stopped evolving, but because moments like that only happen once: when talent, timing, friendship, and fate collide.

Although they’re no longer together, some are dead, and some are still living, in my life, and in yours too, The Beatles can never be forgotten. ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ what comes next, but one thing is certain: if any band can soundtrack generations for years to come, John, Paul, George, and Ringo can certainly ‘Carry That Weight’.

Thank you for reading

Jack x