Spike Island: A Cultural Cornerstone, or A Bad Stone Roses Gig?

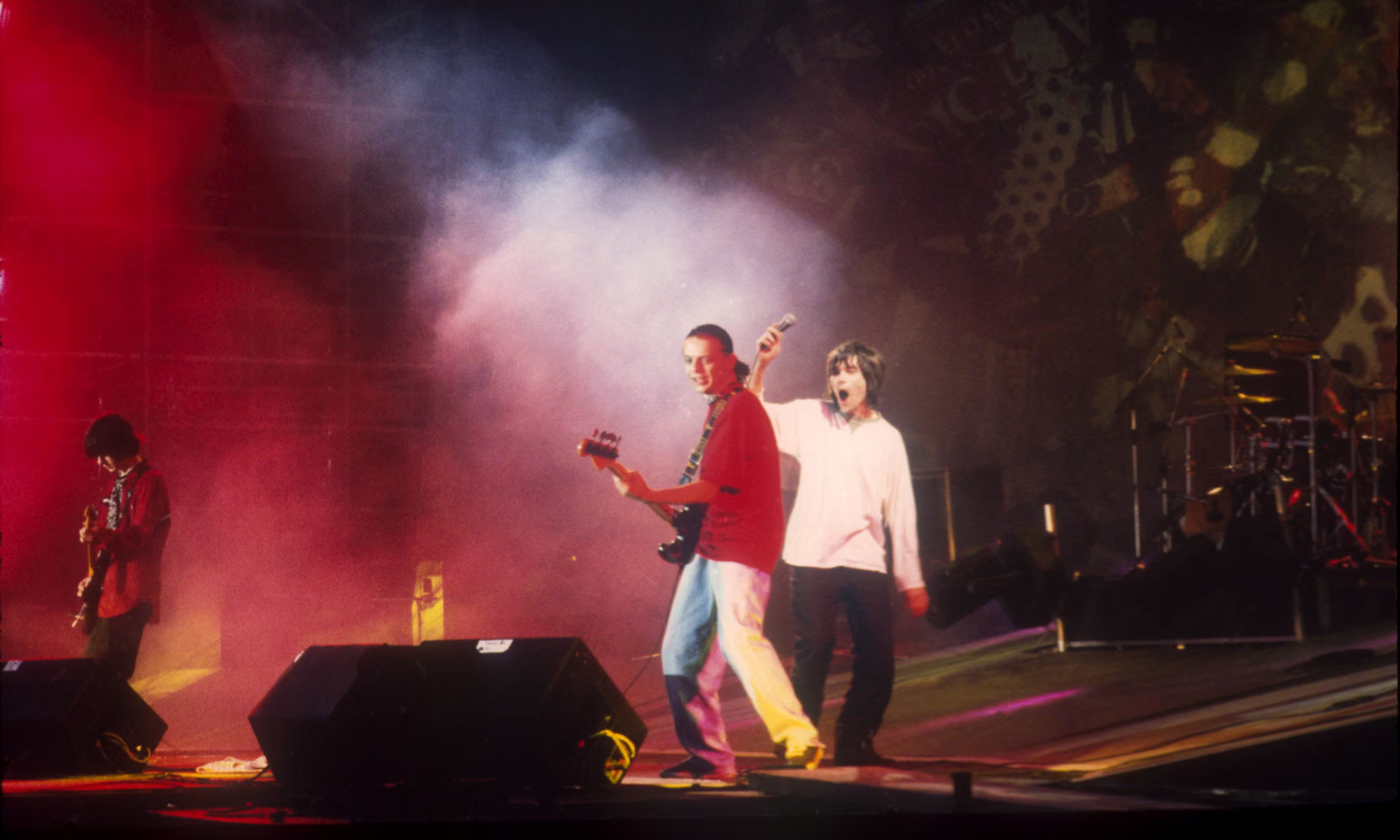

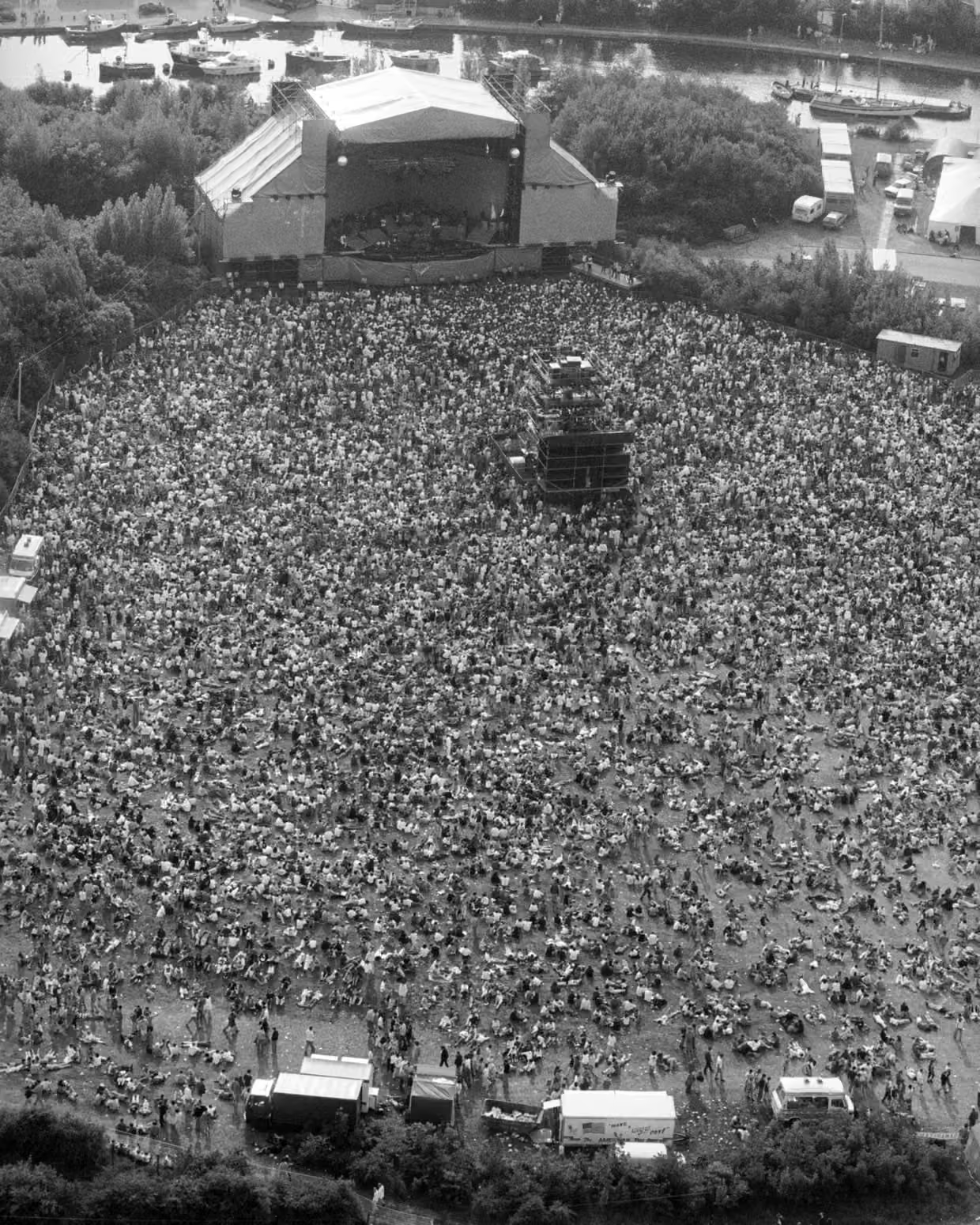

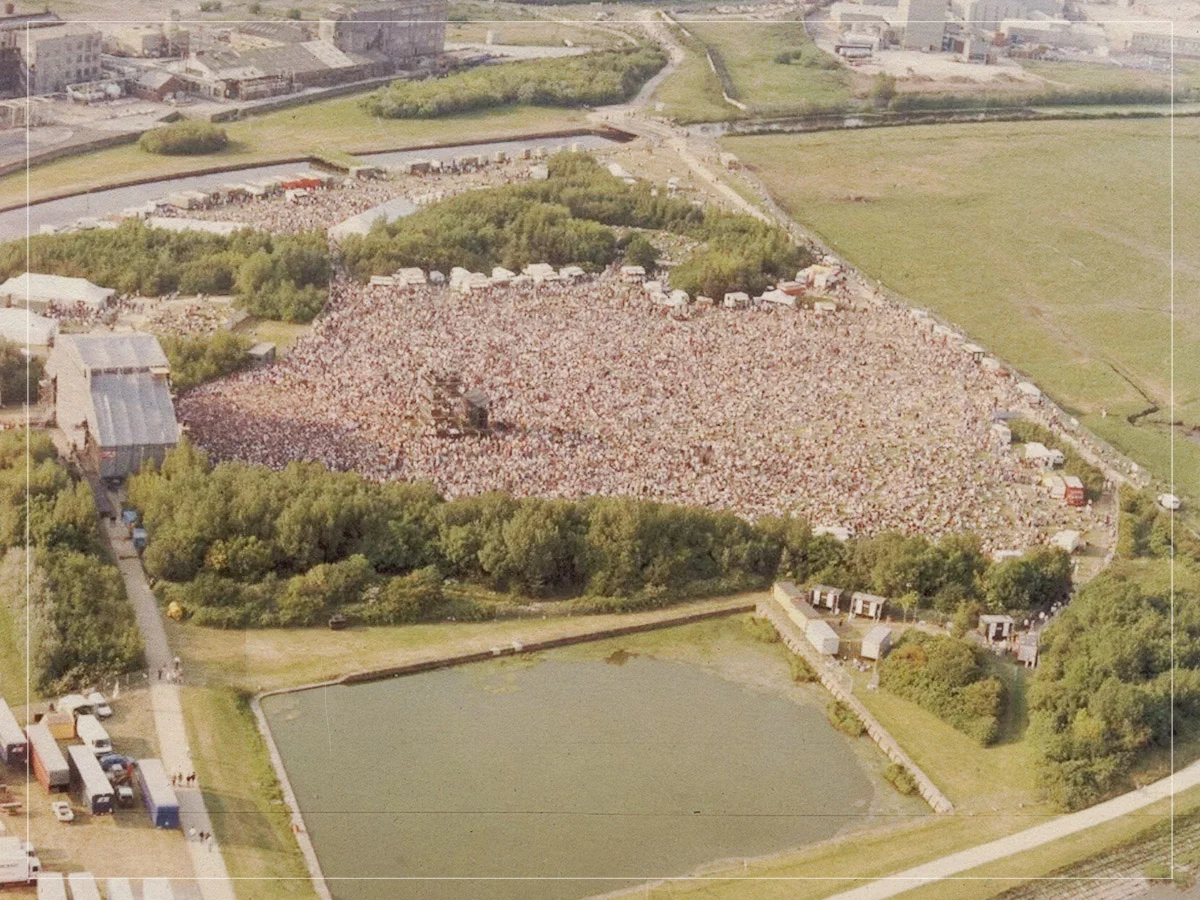

The 27th May 1990, Widness, Cheshire. The Stone Roses step out on stage in front of 27,000 people, surrounded by the remains of a decaying Northern Britain. The Britain that Thatcher had forgotten.

Now, depending on who you ask, this is the most important British concert ever, an event that united the indie kids and the ravers or a poor event marred by bad organisation, bad sound and mismanagement. So which was it?

Now I'll start with this point. I wasn't there; the concert happened ten years before I was born, and everything I comment on in this post comes from various sources from those who were.

Spike Island Itself

The venue was not the most natural for a concert. A man-made island in the Mersey Estuary just outside the town of Widness. The band and their management had spent months scouting out locations for potential shows, visiting quarries, speedway tracks and caravan parks around the UK, but none of them until Spike Island had hit the mark.

From Industrial Decay to Indie Mecca

The island was originally pivotal in the Industrial Revolution, built between the Sankey Canal and the Estuary of the River Mersey. In 1833, Widnes Dock, the world's first rail-to-ship dock, was built on the island. In 1848, John Hutchinson built the first chemical factory in Widnes on the island. The chemical industry in Widnes grew rapidly thereafter. By the 1970s, no working chemical factories remained, and from 1975 onwards, the island was cleaned up and turned over to public recreation.

Despite being used for public use, it was not fit to host a concert; the band and management would be required to build bridges, monitor tides and ensure that people were safe on the Island.

However, none of this seemed to phase the band's management and the local authorities. Concert promoter Phil Jones said, “It was Gareth [Evans, Stone Roses manager] who came up with the idea of Spike Island. “It was near where he lived, and they’d had events on there in years gone by, so myself, Gareth and Roger Barratt, who ran a company called Star Hire and who’d already agreed to do the staging, went out there, took a look around and said, ‘Yeah, we can do this here.’ The council were there, we’d already worked out what the capacity would be, and we all shook hands on it that afternoon.”

Guerilla" Event Planning: Avoiding the Circuit

The Stone Roses once professed that they wanted to play a gig on the moon; a reclaimed toxic waste dump was a far cry from that. However, that was part of the appeal; the traditional big venues would have been available for The Stone Roses, but they were part of the Madchester movement, and all of the band had spent the last few years in raves and warehouse parties.

Ian Brown told the NME in 2010, “We wanted to do something outside the rock’n’roll norm and do it in a venue which had never been used for that sort of thing before. This was back in the days of raves, remember. We started out doing warehouse parties, and we still had that mentality where we wanted to play different venues. We wanted to play places that weren’t on the circuit.”

The Band

Spike Island felt like an event, and an important one, but The Stone Roses hadn't played live together for six months, and no one was sure if the gig would go ahead.

Paint, Prisons, and Press Conferences

The band had a criminal damage case hanging over them, brought against the band by their former label boss (they’d daubed his office, cars and girlfriend in paint as retaliation for a ‘Sally Cinnamon’ video he’d commissioned against their wishes), which meant the threat of prison was hanging over their heads. Much to their relief, they eventually escaped with a fine.

A short warm-up tour of Scandinavia to get the band ready for Spike Island hadn't exactly gone to plan. Before a note was even played, the band's press conference was nothing short of a catastrophe. Reporters from both the BBC and ITV refused to cover the event when Gareth Evans tried to charge them for access, and the surly and uncommunicative band were accused by one journalist of “treating these people like fucking shit”.

Despite this run-up to the show, the demand for Spike Island was still there. Nothing like this had been done by an independent group before. The Stone Roses were also quite possibly the biggest band in the country, arriving just at the fag end of Thatcherism. A bridge between the past and the future, between ’60s psychedelia and the burgeoning acid house scene. The posterboys of Madchester, of a new sound, a new style and in ecstasy, a new drug. Ian Brown, the band's frontman, spoke of killing the Queen and becoming bigger than The Beatles, and for a brief moment, both seemed within the realms of possibility.

Thatcher’s Children and the New Optimism

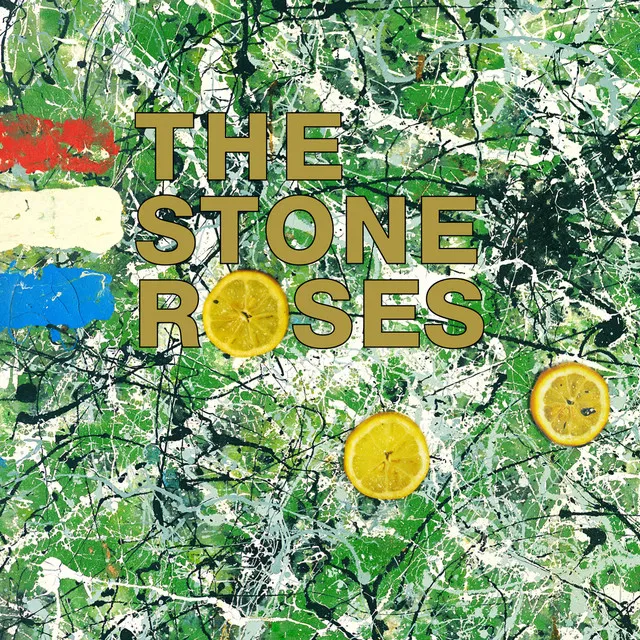

They had the songs to back it up, too. The band's debut album wasn’t just a record. It was a statement of intent. Across the U.K., a generation worn down by economic hardship and political disillusionment suddenly had something to rally around: a fresh sense of optimism, a streak of rebellion, and a renewed feeling of unity. “The past was yours, but the future’s mine,” they declared, a line that didn’t just reflect the moment, but helped define it.

For the first time in years, Thatcher’s children glimpsed hope. The band’s swaggering confidence reverberated through every venue they played, offering young people a lifeline out of the stagnation and joblessness that had shaped their lives. The Stone Roses weren’t just speaking for a generation; they were inspiring the next.

The Chemistry: A Working-Class Masterpiece

The magic lay in the chemistry. Ian Brown’s cryptic, charismatic vocals. John Squire’s shimmering, intricate guitar textures. Mani’s groove-heavy basslines. Reni’s genre-defying drumming more funk and reggae inspired than their indie peers. Together, they created a sound that was both swaggering and spiritual, rooted in the past but bursting with the promise of the future.

The album’s brilliance is found not just in its innovation but in its emotional range. 'I Wanna Be Adored' opens the record with eerie confidence, a slow-burning declaration of intent that morphs into something hypnotic. 'She Bangs the Drums' is pure euphoria, a bright, melodic rush that captures the joy of youthful idealism. 'Waterfall', with its cascading guitar riffs and lyrical escapism, feels like a moment of pure liberation, while its seamless transition into 'Don’t Stop', a reversed, dreamlike reworking, was the kind of psychedelic experimentation that few other bands dared attempt at the time.

Then there’s 'Made of Stone', one of the band’s most enduring tracks, melancholy, mysterious, and emotionally charged. 'This Is the One' feels like a rallying cry, full of tension and release, while 'Elizabeth My Dear' delivers a sharp political jab in under a minute, cloaking its anti-monarchist message in the melody of 'Scarborough Fair'. And of course, 'I Am the Resurrection' closes the album with an explosive two-part finale, four minutes of righteous defiance followed by four more of blissed-out instrumental jamming that pointed the way to the Madchester sound.

As Clash Magazine put it, the album remains “an overwhelming statement of working-class pride.” It wasn’t music for the elite or the critics; it was for the dreamers, the dancers, the disillusioned youth looking for meaning and escape.

The Gig

This is the part that's up for debate. There's no doubt at all that Spike Island was an important moment within the band's history, a mass gathering of the people. However, when reading about the concert, both for this research and in the past, most people say it wasn't very good, including the band themselves!

A Shambolic Reality: "Organised on a Fag Packet

David Barnett of The Guardian was at the concert, and he described his feelings on the show.

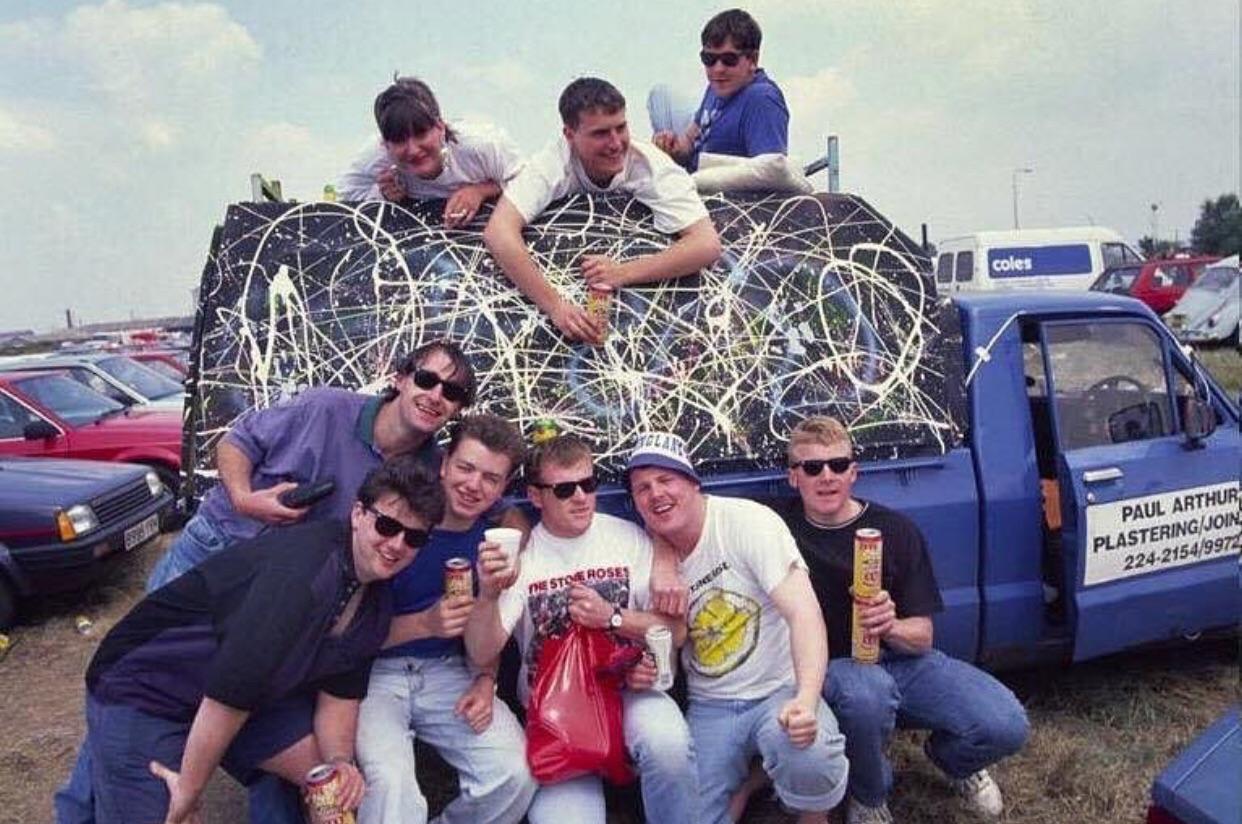

"The weekend of the gig, a colleague and I borrowed a van from our place of work, emblazoned with the paper’s masthead. I think we said we were going to cover a flower show, or maybe a non-league football game. We loaded up with mates and booze and set off for Cheshire. I’d been to Reading and Glastonbury so I thought I knew what to expect. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Spike Island was like Glastonbury, had it been organised on the back of a fag packet by half a dozen stoners in a beer garden.

High metal fences gave it the feel of a high-security prison (this was 12 years before Glastonbury installed theirs). It seemed impenetrable, even for those with tickets. Nobody seemed to know how you got in. Every entrepreneur in the north was selling hooky T-shirts, posters and hats. Inside was a sea of bucket hats and fake designer labels. Everybody was off their head. There weren’t enough toilets, nor enough drinks, nor enough space. There was an aura of menace."

This seems to be a common theme when discussing the concert. It seemed to have been organised by a lot of people who didn't know what they were doing.

Maybe the idea of Spike Island was better in people's heads than actually happening.

Ian Brown and Mani confirmed the issues that fans had faced. When they arrived on site, not in a helicopter, as has been reported, but in a rented minivan, they were unimpressed by the heavy-handedness of the security and the apparent lack of facilities. “The organisation was shambolic,” Ian Brown told NME in 2010. “The PA wasn’t big enough for a start, and certain things were going on that we didn’t know about. The management was taking people’s sandwiches off them at the gate to force them to buy five-quid burgers when they got in. Some kid got impaled. He broke out of jail, tried to jump the railings and ended up leaving his bollocks on top of them. We were still finding out about this stuff two, three years later.”

“Our management really fucked up,” agreed Mani. “There were security guards taking booze off people, there was a lot of overcharging for food and drink, and there weren’t enough facilities on-site. There were a lot of aspects of Spike Island that were really badly thought out, but none of that is the band’s job.”

Tides, Toxins, and the Silent PA

Alongside the long queues and heavy-handed security. Two natural occurrences made the show for some awful, and for others, nearly fatal. As with many Stone Roses shows, there were no support bands; instead, a series of DJ performances throughout the day. The task of keeping the energy alive fell to the DJs, including the Haçienda’s Dave Haslam and a young Paul Oakenfold. They played everything from Italian House to 60s Soul, essentially turning a rock concert into the UK's largest-ever open-air rave before the band even stepped on stage.

However, without a support band, it meant that the PA had not been tested properly. It was vastly underpowered, and when the wind changed direction as it quite often does in an Estuary, the crowd were unable to hear anything.

With the show also being on an Island, the band and management had to build bridges to ferry people to the show. They also had to consider the tide. This nearly brought a stop to the whole event. Jones recalls the panic he faced. “I was standing on the stage with the deputy chief constable of Cheshire, Widnes division, who told me, ‘It’s a spring tide, Phil. It’s never gone over this island before, but it is getting very high. If it goes past a certain level, you’re going to have to get everyone off.’ It was a high neap tide on a full moon, which is the highest tide you can get. It never came close in the end, but that was the worst moment."

Phil Jones, the promoter, however, disputes the claims that the show was awful. “There were 30,000 people there, and 29,990 of them had a whale of a time. Whenever I read about Spike Island, it’s always negative. Show me firm evidence that the sound wasn’t good. And the lights were the best fucking lights I’d ever seen. What we had on that stage was state-of-the-art. We didn’t scrimp on the PA, either, but the council wouldn’t allow it to go above a certain decibel level.”

The Setlist: 75 Minutes of Anthemic Chaos

The Spike Island setlist wasn't just a collection of hits; it was a carefully constructed journey. Despite the underpowered PA and the swirling winds, the 15-track set captured a band at the exact moment they were outgrowing the "indie" label and becoming something much more experimental.

The performance was famously split into two halves. The first half leaned into the jangly, melodic power of the debut album songs like 'She Bangs the Drums' and 'Sally Cinnamon' provided the high-energy sing-alongs that the crowd craved. However, as the sun began to set over the Mersey, the band shifted into a deeper, more hypnotic gear.

The centrepiece of the show was undoubtedly 'Fools Gold'. At Spike Island, this track acted as the bridge between the 80s and the 90s. With its breakbeat-style drumming from Reni and John Squire’s wah-wah-infused guitar work, it was the moment the "indie" kids realised they could dance.

The set finished with an elongated version of 'I Am the Resurrection'. While the first half of the song was a righteous anthem of defiance, the final four minutes descended into a blissed-out, instrumental jam. It was a bold statement: the Roses weren't just a pop group anymore—they were a force of nature, content to lose themselves in the groove while 27,000 people stood in awe on a reclaimed toxic waste dump.

The Lost Footage

We don't know how good or bad it was, really, as the show was never filmed professionally, at least. A camera crew from Central Music TV were present, but at the last minute, the band instructed them to stand down. The only footage that exists of the gig was shot on a fan’s camcorder, which is one of the reasons why no one who was there seems able to agree on whether the performance was second-rate or sublime.

NME’s Andy Fyfe remembers them playing “abysmally. Colleagues who went to the soundcheck the day before said it was amazing, electrifying, they were on top form, but from what I recall, they had no funk to them at all. There was a certain weight of expectation that they didn’t live up to.”

The circumstances in which Spike Island was completed were far from ideal. It was played on an island that had never hosted a gig, by a band that had played live once in six months. Outdoor shows in general were uncommon at this time anyway. Open air ones at least, there hadn't been too many Led Zeppelin and Queen at Knebworth, which were the two big ones.

Ultimately, it was an attempt to try something new and brave, to help usher in a new decade, and give kids a sense of hope. David Barnett said, "Driving home in the Chorley Guardian van, somebody said: Well, that’s the 80s over. It felt true. The old regimes across Europe and the Baltic states were collapsing, and Germany was reunifying. Thatcher went six months later."

Aftermath

The Stone Roses would never be the same band after Spike Island. It marked the beginning of the end. They would release a further single, 'One Love,' and then take four years to record their second album, and by that time, Madchester was over, music had changed.

Jon Ronson said, “It didn’t feel to me like the start of something as the end of it – the ideal place to bring down the curtain on what it had been. The record had been out for a year by then, and because the Roses didn’t release another record for so many years afterwards, it framed perfectly the summit of what they’d become and what they meant to people.” A quarter of a century on, it’s a summit few bands have ever come close to scaling.

The Blueprint for a Generation: From Widnes to Knebworth

The show would influence the next generation of musicians. Noel Gallagher was at the show. Saying of the show in the 2003 documentary 'Live Forever'

"It was a shit gig, from a technical view, the wind was blowing the sound all over the place. I don't think I got to hear one song properly. But that wasn't the point. The point was that there were all of those people there. Spike Island was the blueprint for my group; we were then going to become the biggest band in the world, and The Stone Roses, and their impact stretches so far beyond the music and that gig. They did not need to play a note; the job was already done."

The founding members of Oasis, Paul 'Bonehead' Arthurs and Paul 'Guigsy' McGuigan, were at the show together.

Spike Island Come Alive": The Pulp Connection

Jarvis Cocker would later write two songs about the event, twenty-five years apart. The first, ‘Sorted for E’s and Wizz’ from Pulp’s album ‘Different Class’, was inspired directly by stories from the show. Reflecting on the song, Cocker recalled speaking to “a girl that I was speaking to at The Leadmill (nightclub) in Sheffield one night. She said all that she could remember was people going around saying, ‘Is everyone sorted for E’s and wizz?’ So that phrase stuck in my mind.”

Although Cocker wasn’t at the show himself, he was shaped by the memories of two people who were: first, the girl at The Leadmill, and later, more than twenty years on, Jason Buckle of All Seeing I. Cocker wrote ‘Spike Island’, the lead single from their 2025 album ‘More’, with Buckle.

“All he could remember was a DJ who, between every song, said, ‘Spike Island come alive, Spike Island come alive’,” Cocker said.

Two of the biggest bands of the 1990s can have The Stone Roses to thank. Noel Gallagher kept his word, six years after being on that island in Widness. He, Bonehead, Guigsy, Alan White and his younger brother Liam would play to 125,000 people at Knebworth in Hertfordshire. To complete the circle, Oasis would invite John Squire to sprinkle some magic on 'Champagne Supernova' and 'I Am the Walrus'.

Conclusion

So, which was it? A cultural cornerstone or a disastrous gig?

The truth is, Spike Island was both. It was a failure of logistics but a triumph of spirit. While it may not have shown The Stone Roses at their technical best, it proved that a band from the North could bypass the industry "norms" and summon a 27,000-strong army to a reclaimed wasteland. It was the moment the swagger of the 60s met the euphoria of the 90s, creating the blueprint for everything from Knebworth to Glastonbury’s Pyramid Stage.

I often wonder how history might have shifted if the Mersey winds had been calmer, or if the band had harnessed that momentum to release 'Second Coming' in 1991 instead of 1994. Perhaps the "Madchester" high would have lasted forever.

But in the end, the imperfections are what make Spike Island legendary. It remains a beautiful, chaotic mystery, a summit scaled by four lads from Manchester who, for one afternoon, made a toxic island feel like the centre of the universe.

We can only speculate.

Thank you for reading.

Jack