Six Of the Best

In 1982, seven years after his departure, Peter Gabriel had to unite with his former band in very unique circumstances.

Gabriel Goes Solo

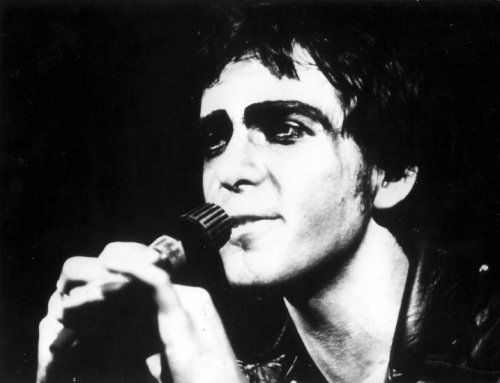

Peter Gabriel left Genesis in 1975. 'The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway' had been a difficult period for him personally. The birth of his first daughter had proven difficult, and he had to spend some time away from Genesis. The other members complained that Gabriel was showing a lack of commitment to the band. Gabriel saw this as a "really unsympathetic handling of my dealing with a family crisis" and said it caused a breakdown in his relationships with the rest of Genesis; Rutherford later admitted that they had been overly fixated on their music and were very unhelpful in what must have been a difficult time for Gabriel.

The album was eventually finished, and early into the album's tour, Gabriel informed Genesis that he planned to leave after the tour had finished. Mike Rutherford, the band's guitarist, has recalled in recent years that they all "could see it coming". The tour ended in May 1975, after which Gabriel wrote a piece for the press on 15 August, entitled "Out, Angels Out", about his departure, his disillusion with the business, and his desire to spend time with his family. The news stunned fans of the group and left commentators wondering if the band could survive without him. His exit resulted in drummer Phil Collins reluctantly taking over on lead vocals after 400 singers were fruitlessly auditioned.

Gabriel described his break from the music business as his "learning period", during which he took piano and music lessons. He had recorded demos by the end of 1975, the fruits of a period of writing around 20 songs with his friend Martin Hall.

His self-titled debut album, often referred to as ‘Car’, introduced audiences to his unique artistic vision. The song that launched his solo career, ‘Solsbury Hill’, was the first single from 1977’s ‘Car’, and even all these years later, it remains one of his most beloved and enduring works. Written about his decision to leave Genesis, the song marked a stark change from the elaborate prog epics of his past.

Much more introspective, concise, and personal, it captured the uncertainty and exhilaration of stepping into the unknown. Gabriel wrote it after a spiritual experience atop Solsbury Hill in Somerset, England, and within the song’s opening lines, he transports the listener directly into that moment of clarity and revelation:

“Climbing up on Solsbury Hill / I could see the city light / Wind was blowing, time stood still / Eagle flew out of the night.”

These words paint a vivid picture, grounding the listener in both the landscape and Gabriel’s state of mind. The eagle becomes a symbol of freedom and transformation, and the song as a whole stands as a metaphor for leaving the safety of Genesis to pursue a solo identity on his own terms.

Other standout tracks on the album, such as ‘Modern Love’ and ‘Here Comes the Flood’, further showcased his willingness to explore intimate themes with intricate arrangements and lyrical subtlety, signalling that Gabriel’s solo work would be both personal and musically adventurous.

Gabriel’s second album, ‘Scratch’, continued to push boundaries, diving further into experimental territory with a raw, edgy sound that challenged expectations. Tracks like 'Mother of Violence', ‘On the Air’ and ‘DIY’ captured a sense of urgency and restlessness, blending post-punk energy with progressive textures. The album leaned heavily into angular arrangements and dense production, reflecting Gabriel’s interest in technological innovation and psychological introspection. While it received mixed reviews at the time, ‘Scratch’ was a bold statement, uncompromising and unafraid to be abrasive, laying the necessary groundwork for what was to come.

However, it was his third self-titled release, ‘Melt’, that truly marked a turning point in his career, both artistically and thematically. Abandoning traditional song structures and rock tropes, Gabriel embraced a darker, more atmospheric sound, working with producer Steve Lillywhite and engineer Hugh Padgham to pioneer gated reverb drum effects that would go on to define an entire era of production. ‘Melt’ struck a remarkable balance between sonic innovation and emotional resonance. Tracks such as ‘Intruder’ and ‘Family Snapshot’ demonstrated Gabriel’s mastery of tension and mood, using stark arrangements, claustrophobic rhythms, and unsettling textures to pull the listener into the psychological landscapes of his characters. ‘Here Comes the Flood’ revealed his ability to convey deep emotional vulnerability through minimalistic arrangements. This is the record where he does it best, though.

'Biko' is one of Gabriel's most political songs, and it brings the 1980 album 'Melt' to a close. Written in response to the South African anti-apartheid activist Steven Biko, the song stands out as one of Gabriel's best.

Musically, ‘Biko’ is both stark and unforgettable. Built on a hypnotic, unrelenting rhythm, the track incorporates African-inspired drumming patterns, heavy toms and booming bass. Layered on top are mournful synthesisers and, unexpectedly, bagpipes, whose droning, keening sound adds a funereal and universal dimension to the arrangement. The blend of African rhythm and European instrumentation underscores Gabriel’s vision of a global, borderless sound that speaks to shared human struggle.

The song's structure is deliberately minimal; Gabriel wants you to sit and listen to the lyrics, because they vividly paint a picture of what happened to Steven Biko, as well as the world's reaction to it. The song's lyrics include phrases in Xhosa, describe Biko's death and the violence under the apartheid government. The song is book-ended with recordings of songs sung at Biko's funeral: the album version begins with "Ngomhla sibuyayo" and ends with "Senzeni Na?", while the single versions end with "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika".

More than any other song in Gabriel’s catalogue, ‘Biko’ transcended music to become a force for awareness and change. It brought global attention to apartheid, introduced audiences to Steve Biko’s story, and became an anthem of resistance at benefit concerts around the world.

The song has been credited with creating a "political awakening" both in terms of awareness of the brutalities of apartheid and of Steve Biko as a person. It greatly raised Biko's profile, making his name known to millions of people who had not previously heard of him.

One of its most enduring tracks, ‘Games Without Frontiers’, expanded Gabriel’s songwriting from the personal to the political. The title references the European TV show Jeux Sans Frontières (“Games Without Borders”), where teams from across nations competed in outlandish challenges. Gabriel deftly twisted this harmless spectacle into a biting metaphor for the petty, dangerous rivalries between global powers. His lyrics highlight how the absurdities of play mirror the brinkmanship of war, exposing the childishness at the core of international conflict.

The song also featured one of Gabriel’s most inspired collaborations: Kate Bush’s ethereal backing vocals. Her ghostly whispers of “jeux sans frontières” float hauntingly through the track, a playful yet chilling counterpoint to the satire at its heart. Musically, the song embodies the experimental spirit of ‘Melt’. Its taut, cymbal-free groove, built on Tony Levin’s percussive Chapman Stick and Jerry Marotta’s stark drumming, creates a sense of unease that perfectly complements Gabriel’s deadpan and sometimes mocking vocal delivery. ‘Games Without Frontiers’ became Gabriel’s first major solo hit in the UK, breaking through to a wider audience without sacrificing its artistic edge.

From start to finish, ‘Melt’ showcased Gabriel’s fearless willingness to confront both personal and political themes, blending innovation in production with emotional intensity. The album cemented his reputation as a visionary artist unafraid to explore darkness, complexity, and the unpredictable possibilities of the human psyche.

By the time of his fourth self-titled album, often nicknamed ‘Security’, Gabriel had fully embraced world music influences, synthesisers, and complex rhythmic layering, pushing the boundaries of what mainstream rock could encompass. The album was a bold fusion of art-rock experimentation with global sounds, drawing on African, Latin American, and Middle Eastern percussion traditions, as well as unconventional time signatures that challenged listeners while enriching the emotional and physical impact of his music.

Tracks like ‘Shock the Monkey’ revealed Gabriel’s fascination with primal emotion and psychological intensity. The song’s driving synth patterns, interlocking percussion, and echoing guitar textures create a sense of tension and release, while the lyrics explore themes of jealousy, obsession, and the darker sides of human instinct. ‘San Jacinto’, by contrast, demonstrated his interest in ritual and cultural identity, using sparse instrumentation, chant-like vocals, and evocative soundscapes to evoke both historical narrative and spiritual resonance.

Other tracks, such as ‘The Family and the Fishing Net’, continued this synthesis of personal introspection with larger cultural and political concerns. Gabriel’s meticulous production techniques, layering electronic textures over organic percussion, manipulating vocals, and experimenting with spatial effects, allowed each track to feel both immediate and otherworldly. The album as a whole established a thematic and sonic blueprint that would continue to shape his work throughout the 1980s and beyond: a fearless exploration of human emotion, identity, and global interconnectedness, rendered through a groundbreaking combination of technology and world-inspired musicality.

‘San Jacinto’, one of the album’s most profound moments, demonstrates Gabriel’s unique ability to translate human experience into sonic storytelling. The track was inspired by a real-life encounter Gabriel had while on tour in the United States. He met an Apache man working at the same hotel where Gabriel and his band were staying. The man had just learned that his flat had burned down, yet what concerned him most was the fate of his cat. That perspective impressed Gabriel deeply, and during their drive together, the man shared stories of his initiation into tribal life: tales that would eventually form the heart of ‘San Jacinto’.

The Apache man described being taken into the mountains as a boy by a medicine man, carrying a rattlesnake in a bag. The snake was placed on his arm to deliver a bite, and he was left in the wilderness to survive for fourteen days. If he returned, he was considered brave; if not, he perished. According to the man, he endured, though the trial involved intense hallucinations and spiritual visions. Gabriel was struck by this raw and transformative rite of passage, and it became the backbone of the song’s narrative.

Musically, ‘San Jacinto’ mirrors this tension between the sacred and the commercial, the timeless and the contemporary. It's slow build, atmospheric synths, and powerful crescendos capture the hallucinatory intensity of the initiation process, while Gabriel’s voice, alternately hushed and soaring, conveys both pain and resilience. The refrain “I hold the line” reflects the young initiate’s determination to survive, turning the song into both a personal and cultural anthem of endurance. More than just a political or spiritual statement, ‘San Jacinto’ is a deeply empathetic piece, born from Gabriel’s willingness to listen, observe, and translate human stories into art a quality that would recur throughout his career.

‘Security’ was more than a collection of songs; it was a statement of intent, asserting Gabriel as an artist unafraid to challenge both himself and his audience. By fusing rhythm, narrative, and sonic innovation, he created an album that was simultaneously intellectually stimulating, emotionally affecting, and rhythmically compelling, influencing countless musicians in its wake and solidifying his status as a visionary of modern music.

WOMAD

Gabriel’s vision for WOMAD (World of Music, Arts and Dance) began to take shape in the late 1970s, rooted in his growing fascination with global music traditions and his desire to expose Western audiences to sounds and performances they might never otherwise encounter. His experiences collaborating with musicians from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, particularly through his solo recordings and live performances, convinced him that music could be a bridge between cultures, a universal language capable of fostering understanding and creativity.

In 1980, Gabriel formally launched WOMAD alongside a small but dedicated team: Thomas Brooman, Bob Hooton, Mark Kidel, Stephen Pritchard, Martin Elbourne, and Jonathan Arthur. Each member brought complementary expertise: Brooman and Kidel had deep experience in music programming and production, Elbourne contributed insights from the live music industry, Pritchard and Hooton provided logistical and organisational support, and Jonathan Arthur helped shape the festival’s broader cultural and outreach strategy. Together, they shared Gabriel’s belief that music could be a tool for social as well as artistic impact.

The founding of WOMAD was about more than creating a festival; it was an effort to establish a sustainable platform for cultural exchange. Gabriel envisioned a festival that would allow artists from diverse traditions to collaborate, experiment, and reach new audiences, while also encouraging education, workshops, and discussion around global music and dance. In many ways, it was a proactive response to the growing homogenization of mainstream music in the UK and the West, a conscious effort to create space for innovation, diversity, and artistic authenticity.

WOMAD’s structure reflected this ethos. It was designed to be flexible and inclusive, capable of showcasing a wide range of musical genres from traditional African drumming to Indian classical music, from jazz improvisation to experimental fusion alongside dance, visual arts, and storytelling. This multidisciplinary approach emphasised not only performance but engagement, encouraging audiences to experience the cultural context behind the music.

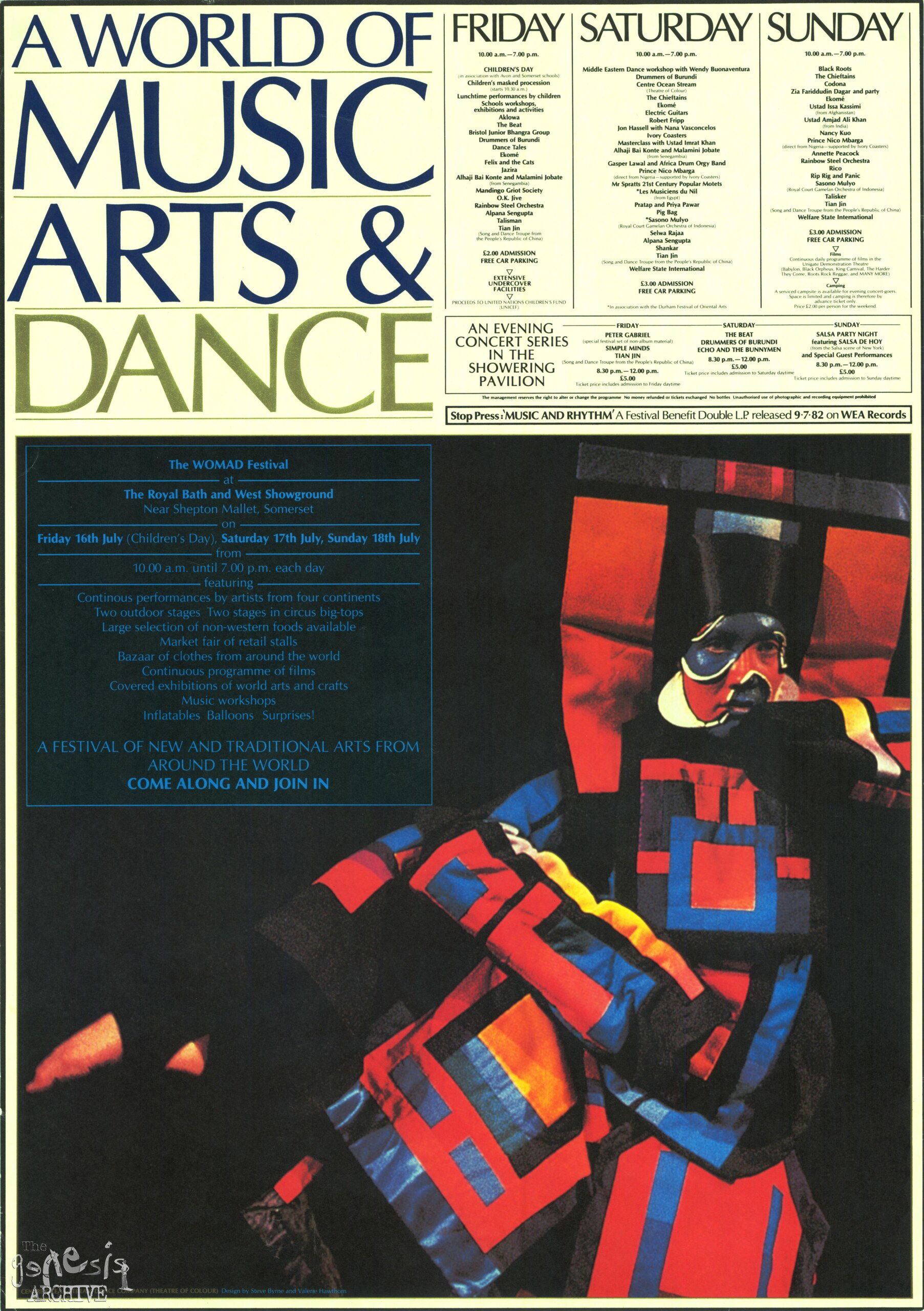

The first WOMAD festival, held in 1982 in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, was the culmination of this vision. It featured an unprecedented lineup, bringing together artists such as Don Cherry, The Beat, Drummers of Burundi, Echo & The Bunnymen, Imrat Khan, Prince Nico Mbarga, Peter Hammill, Simple Minds, Suns of Arqa, The Chieftains, and the Ekome National Dance Company, founded by Barrington, Angie, Pauline, and Lorna Anderson.

Gabriel’s own performance at the festival exemplified WOMAD’s core principle of cross-cultural collaboration. In addition to integrating the Ekome National Dance Company into ‘The Rhythm of the Heat’, he performed other key tracks from his recent albums, including ‘Shock the Monkey’, ‘I Have the Touch’, and ‘San Jacinto’. These performances fused his art-rock sensibilities with the rhythms, instruments, and vocal styles of the participating world music artists, creating a dynamic dialogue between Western pop/rock and global traditions. The inclusion of live African drums, percussion ensembles, and traditional dance not only amplified the energy of the stage but also highlighted Gabriel’s commitment to presenting music as a living, interactive cultural exchange rather than a mere performance

Despite this, the company and Gabriel himself faced severe financial difficulties. Several factors contributed to the crisis: poor weather on the weekend of the festival dampened attendance, a national rail strike disrupted transport to the venue, and the concept of a world music festival was still so new in the UK that it struggled to attract mainstream attention. Limited publicity, coupled with public unfamiliarity with many of the artists, led to disappointing ticket sales. The venture left Gabriel in considerable financial hardship, with debts reportedly reaching as high as £200,000. Beyond the financial strain, the challenges also took an emotional toll: he received “a lot of nasty phone calls” and even a death threat.

WOMAD had been an artistic success but a commercial failure. Gabriel needed funds, and he needed them quickly.

Reunion

The dire situation was alleviated when Gabriel’s manager, Tony Smith, suggested a one-off Genesis reunion concert to help cover his debts. Smith was also the manager of Genesis, and he believed that a reunion was possible. Genesis were out on the road with their Three Sides Live tour, had the necessary equipment and staging. The tour concluded with three nights at London’s Hammersmith Odeon (September 28–30), during which the band rehearsed a revised setlist with Gabriel. Steve Hackett, who was recording in Brazil, flew in to join rehearsals.

The event, dubbed Six of the Best, took place on October 2, 1982, at the Milton Keynes Bowl in the UK, coinciding with Mike Rutherford’s 32nd birthday.

Despite the goodwill of his former bandmates, Gabriel approached the reunion with mixed emotions. Speaking to NME, he said, “Having tried for seven years to get away from the image of being ex-Genesis, there's obviously a certain amount of stepping back … I’m very grateful and I’m intending to enjoy myself.”

The concert drew an estimated 40,000 attendees, with tickets priced at £9 in advance and £10 on the day. One thing that seems to have been many peoples key memory from the event, was the rain. According to recounts from the band and the fans who were there, it's one of the wettest days ever, and most of the audience were caked in mud.

The bill opened with fellow Charisma Records artists John Martyn, The Blues Band, and Talk Talk, though the latter faced hostility from the crowd, with cans and bottles thrown during their set.

Genesis were introduced to the stage by Jonathan King, who had named the band in 1967 and supervised their first album.

Gabriel’s entrance was theatrical and unforgettable: he appeared in a coffin carried on stage by four pallbearers, returning as Rael, his character from 'The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway', a surprise even to the band. The setlist combined Genesis classics with Gabriel solo material, including ‘Back in N.Y.C.’, the opening verse of ‘Dancing With the Moonlit Knight’, ‘The Carpet Crawlers’, ‘Firth of Fifth’, ‘The Musical Box’, and the full 23-minute version of ‘Supper’s Ready’.

Gabriel’s solo song ‘Solsbury Hill’ was also performed, alongside ‘Turn It On Again’, a Genesis track recorded in 1980, five years after Gabriel had left the band.

Other Genesis classics included ‘The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway’, ‘Fly on a Windshield’, ‘Broadway Melody of 1974’, and ‘In the Cage’. Steve Hackett joined for the two encores, adding his guitar work to ‘I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)’ and ‘The Knife’.

During the performance, Gabriel addressed the audience about the unusual circumstances of the reunion:

“Some of you are maybe wondering what we’re doing here … This is a sequence from a previous event by the name of WOMAD … The end result of this was that it was a great event, and it lost a pile of money. But I’m very lucky to have a group of people [to] support these ideals … And in return for your cash, we will try to give you what we think you would like of this combination.”

Despite minimal rehearsal and the emotional weight of retracing his steps with Genesis, the concert was a historic success. It drew one of Genesis’s largest crowds and remains one of the band’s most unique performances. Although the show was not professionally recorded or filmed, audience bootlegs have preserved the moment. Six of the Best marked a singular convergence of Gabriel’s solo and Genesis careers. He never reunited with the band again. At least on stage.

Aftermath

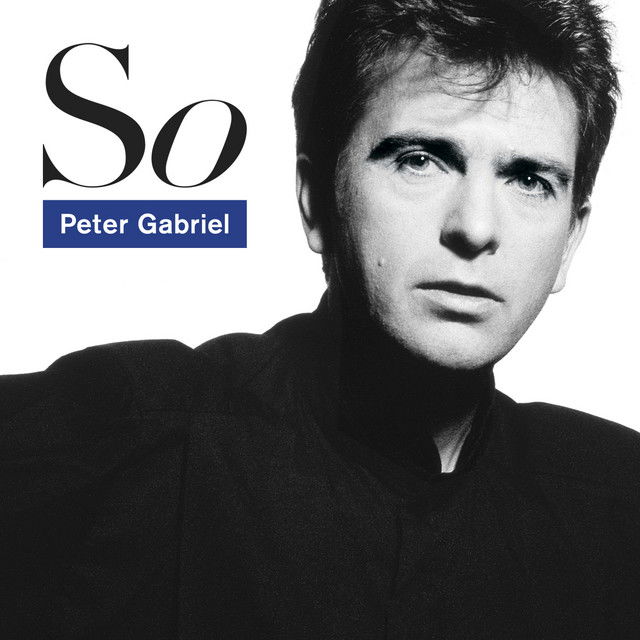

Following the concert. Gabriel returned to his solo career. His fifth solo album ‘So’ arrived in 1986. This record was the album that brought Gabriel unprecedented commercial success without compromising his artistic integrity. The album featured some of his most iconic work, including 'Sledgehammer', a funk-infused, horn-driven hit bursting with energy and soul, powered by an unforgettable music video that revolutionised the medium with its stop-motion animation and surreal visuals. It remains one of the most acclaimed videos of all time, winning a record nine MTV Video Music Awards in 1987.

'Don’t Give Up', a poignant duet with Kate Bush, tackled themes of despair, economic hardship, and resilience. Gabriel’s solemn verses were balanced by Bush’s comforting and angelic chorus, creating a profoundly moving dialogue between vulnerability and hope. 'In Your Eyes', an emotionally resonant centrepiece of the album, blended African rhythms with lyrical intimacy. Its enduring appeal was further cemented when it featured memorably in the 1989 film Say Anything, becoming a touchstone of romantic expression and a mainstay of Gabriel’s live shows.

Other standout tracks included 'Red Rain', an emotionally intense opener that combined vivid, almost apocalyptic imagery with cinematic production, and 'Big Time', a biting satire of ambition and materialism, driven by a propulsive groove and vibrant brass. The album as a whole represented a perfect synthesis of Gabriel’s artistic ambitions and his ability to craft music that was both sonically adventurous and widely accessible.

'So' achieved multi-platinum status and earned critical acclaim across the board, charting globally and garnering multiple Grammy nominations. This global success not only solidified Gabriel’s place as a visionary artist but also as a significant figure in mainstream pop music, demonstrating his ability to reach and resonate with audiences on a massive scale.

By the 1980s, Genesis had undergone a dramatic transformation, embracing a more pop-oriented sound that propelled them to superstardom. The shift began with ‘Duke’ (1980), a pivotal record that bridged their progressive rock past with a more accessible, radio-friendly approach. Tracks like 'Misunderstanding' and 'Turn It On Again' were compact, hook-driven songs that achieved significant chart success, helping Genesis break through to a wider audience. At the same time, the ‘Duke Suite’ a collection of interconnected songs including 'Behind the Lines', 'Duchess', and 'Guide Vocal'—demonstrated that the band had not abandoned their penchant for long-form, concept-driven music. ‘Duke’ was both a commercial and artistic triumph, topping the UK Albums Chart and proving that Genesis could evolve without losing the essence of their identity.

‘Abacab’ (1981) represented a sharper stylistic departure, leaning heavily into stripped-down arrangements, driving rhythms, and bold use of synthesizers. The title track 'Abacab' became a hit single with its angular riffs and propulsive energy, while 'No Reply at All' introduced a horn section that added a funky edge to the band’s sound. Tracks such as 'Man on the Corner' displayed Phil Collins’s growing interest in socially conscious themes and pointed toward his solo career, while 'Me and Sarah Jane' retained elements of their prog roots with shifting structures and layered instrumentation. The album’s willingness to embrace new wave and pop influences helped reintroduce Genesis to a broader audience and marked the true beginning of their 1980s dominance.

The self-titled ‘Genesis’ album in 1983 further cemented this new direction, balancing arena-sized hooks with darker, more atmospheric textures. It included some of the band’s most enduring hits, such as 'Mama', a haunting track driven by a drum machine pulse and Collins’s unsettling vocal delivery, and 'That’s All', a catchy, piano-led single that became their first U.S. Top 10 hit. Other songs like 'Home by the Sea' and 'Second Home by the Sea' blended pop accessibility with extended instrumental passages, demonstrating that the band had not completely abandoned their progressive ambitions. The album’s mix of moody experimentation and polished pop sensibility reflected Genesis’s growing confidence in navigating between mainstream success and artistic depth.

Their commercial peak came with ‘Invisible Touch’ (1986), the album that catapulted Genesis into the stratosphere of global pop stardom. The record was packed with chart-topping singles, including the infectious title track 'Invisible Touch', which became the band’s only U.S. number one single. 'Land of Confusion', with its politically charged lyrics and satirical music video featuring caricature puppets from Spitting Image, became a cultural touchstone of the decade. 'Throwing It All Away' offered a heartfelt ballad that highlighted Collins’s emotive vocals, while 'Tonight, Tonight, Tonight' blended atmospheric synth textures with arena-ready drama. Even deeper cuts like 'Domino' and 'The Brazilian' revealed the band’s continued taste for ambitious, layered arrangements beneath the glossy pop exterior. With five U.S. Top 5 singles, ‘Invisible Touch’ was a staggering commercial triumph, transforming Genesis from a massively successful band into a global pop juggernaut.

In July 1987, the band sold out four consecutive nights at Wembley Stadium as part of their ‘Invisible Touch’ world tour, a staggering achievement that drew over 300,000 fans in total. The run of shows was a high point not only for Genesis but for 1980s live music in general, showcasing the band’s transformation from progressive rock pioneers into a slick, chart-topping powerhouse.

The Wembley shows featured an ambitious setlist that spanned their career, from early prog epics like 'Los Endos' and 'In the Cage' to mainstream hits such as 'Invisible Touch', 'Land of Confusion', and 'Tonight, Tonight, Tonight'. With Phil Collins front and centre, equally charismatic as a vocalist and a showman, the band delivered high-energy performances, backed by dazzling light displays, elaborate staging, and pristine musicianship.

The concerts were recorded and later released as ‘Genesis Live at Wembley Stadium’, capturing the band at their commercial and creative peak. The production values were cutting-edge for the time, with multi-camera coverage and a crystal-clear audio mix that showcased just how tight and dynamic the band had become. For fans and critics alike, the Wembley gigs confirmed Genesis’s status not just as a studio force, but as one of the most successful and polished live acts of the decade.

While Genesis flourished as a group, Phil Collins achieved remarkable success in his solo careers. Collins became one of the most successful solo artists of the decade alongside George Michael. With hits like 'In the Air Tonight', 'Against All Odds', and 'Another Day in Paradise', his pop sensibilities and emotive voice won him fans across the globe, and his solo career paralleled Genesis’ meteoric rise during this period. Beyond his chart-topping singles, Collins contributed heavily to film soundtracks, most famously with his Academy Award–winning 'You’ll Be in My Heart' for Disney’s Tarzan, further cementing his versatility and global reach.

Conclusion

Six of the Best was more than just a one-off reunion; it was a necessary and transformative concert. It gave Genesis fans a final opportunity to witness the classic lineup live, while also providing Peter Gabriel with the financial relief he needed to continue developing WOMAD, a festival that remains a celebrated institution to this day.

The event alleviated Gabriel’s debts and allowed him to fully refocus on his solo career, proving that he could balance both artistic ambition and practical realities. Beyond its impact on Gabriel, the concert demonstrated that Genesis could successfully command large audiences in an outdoor stadium setting, laying the groundwork, both logistically and artistically, for the massive stadium tours the band would undertake five years later. Six of the Best, in retrospect, was not just a reunion; it was a bridge between eras, linking Gabriel’s solo innovation with Genesis’s evolving commercial and creative potential.

Thank you for reading

Jack