It's Not The Beatles, It's Only a DJ: Big Beach Boutique II

Britain has long been defined by its history of culturally tectonic concerts—those rare moments where music and location collide to shift the national mood. We talk about The Rolling Stones at Hyde Park in 1969, a wake for a decade that was ending; Queen’s masterclass at Wembley in 1986; the wind swept unifcation of the clans The Stone Roses at Spike Island in 1990; and the Britpop peak of Oasis at Knebworth.

We even look back at the gargantuan, law-changing scale of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, which saw 600,000 people descend on a single field, and the humanitarian gravity of Live Aid in 1985. We even look back at the gargantuan, law-changing scale of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, which saw 600,000 people descend on a single field, and the humanitarian gravity of Live Aid in 1985.

Yet, 'Big Beach Boutique II', a DJ set by Norman Cook, AKA Fatboy Slim, on Brighton Beach in July 2002, rarely sits comfortably on that same pedestal. This is an oversight of massive proportions. When you consider the sheer numbers, the cultural shift it represented for dance music, and, most importantly, the catastrophic "what if" that loomed over the pebbles that night, it may well be the most significant event of them all.

Build Up

Norman Cook hadn't always been a superstar DJ. In a previous life, he was the grinning bass player for The Housemartins, the quintessential 80s indie band from Hull. While they were famous for the "twinkling guitars" and jangle-pop sensibilities of hits like 'Happy Hour', Cook’s internal compass was always pointing toward the dancefloor. His deep-seated love for funk, soul, and hip-hop was the engine room beneath the Northern indie-pop veneer. By the time The Housemartins folded, he wasn't just ready to move on; he had already begun his metamorphosis behind the decks.

The 90s saw him experiment with various projects like Beats International, but it was in 1996 that the world met Fatboy Slim. His debut album, 'Better Living Through Chemistry', was a masterclass in the Big Beat sound, a high-energy collision of breakbeats, distorted bass, and ingeniously sourced samples. By the turn of the millennium, he wasn't just a musician; he was a brand. After the global success of the 'You've Come a Long Way, Baby' album, he had moved beyond the clubs and into the stratosphere with chart-toppers like 'Praise You' and 'The Rockafeller Skank'.

The seeds for the 2002 chaos were sown a year earlier, almost by accident. In 2001, Channel 4 held an open-air screening of an England cricket match on Brighton’s seafront and asked the local hero to play a set afterwards. To everyone's surprise, 40,000 people showed up for what was essentially a glorified after-party.

Flushed with the success of the first 'Big Beach Boutique', Cook and the organisers decided to go bigger for the sequel. The plan for July 2002 was simple, if tragically optimistic: a free, open-air party for the people of Brighton. They estimated that perhaps 50,000 might attend, a number they believed the beach could "take." They hadn't accounted for the fact that, in the age of the burgeoning internet and cheap rail travel, word of a free party with the world’s biggest DJ would travel far beyond the Sussex borders. They were expecting a crowd; they were about to get a migration.

The Great Underestimation

The run-up to the event was marked by a staggering lack of foresight. While organisers and police held "multi-agency meetings," a prevailing sense of snobbery clouded the judgment of local authorities. Becky Stevens, who worked for Brighton and Hove’s Council on the event, tells us in the 'Right Here Right Now' documentary that she warned planners they could be expecting a bigger crowd than anticipated.

"I clearly remember a senior council officer turning to me and saying: ‘Don’t be silly Becky, this isn’t the Beatles. It’s just a DJ"

The council had estimated 50,000 attenders, but the reality was closer to 250,000.

While the day started peacefully, with the sun shining down and clear blue skies, by 9 am, onlookers claimed that there were over 30,000 revellers already on the beach.

With the crowds spilling out of control, the chief of police considered cancelling the event before Fatboy Slim had even performed. But the security team feared that letting down the 250,000-strong crowd could prove even more dangerous.

The infrastructure of the South Coast simply snapped. The A23 was backed up 25 miles to Gatwick, and abandoned cars were strewn along the coast road to Hove. Several hours before the set began, the beach was a vast mass of people, high on beer, ecstasy, and the Sussex sun. In a live TV interview from his balcony at the Grand Hotel, a visibly shaken Fatboy Slim admitted: “I’m quite scared.” He wasn’t joking.

A City on the Brink

The details of the night make you flinch with anxiety. Security staff, tasked with telling punters at the water’s edge to move before the tide came in, realised the task was impossible and quit en masse. Riot police manning the beach’s groynes, slippery stone barriers with sheer drops, were withdrawn for their own safety. Fearing a fatal crowd crush similar to the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, the police's priority became safety rather than crime. They mobilised an additional 220 officers, and the Metropolitan Police offered assistance.

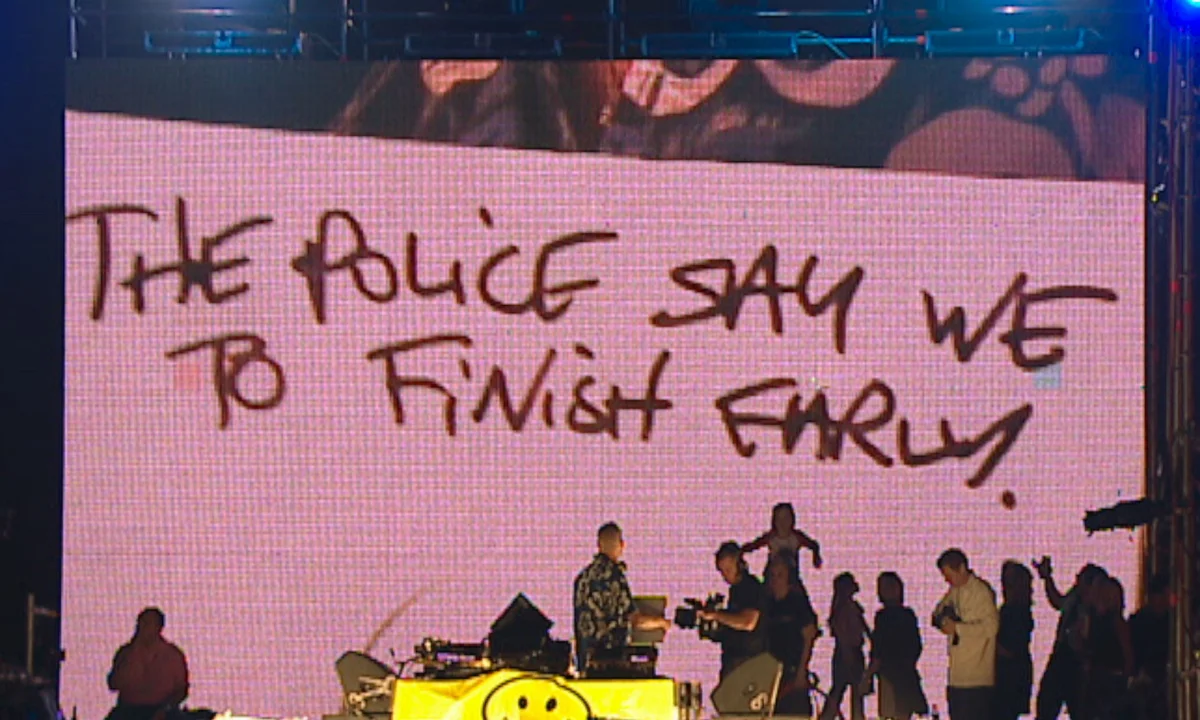

At an afternoon meeting, police told Cook the gig had to go ahead, not because it was safe, but because cancelling it would have triggered a riot. They allowed it to proceed on the condition that Cook finish 30 minutes early.

A Brighton Borough Council official said: "There was a sense that more and more people were pouring into Brighton, a great tide, and there was nothing we could do."

Many off-licences and pubs closed early after selling out their stock, and many in the audience had been drinking for hours. With no way to reach toilets, audience members urinated on the beach and shopfronts and in the sea, and there were no crush barriers or ticketing system to limit the crowd size.

As Cook took the stage, opening with 'It Just Won’t Do' by Tim Deluxe, the sheer physical toll began. The movement of a quarter-million people grinding the stones together created "Pebble Lung", a thick cloud of flint dust that hung over the crowd. As the tide rolled in, the available space shrank, forcing bodies into a precarious crush against the promenade walls.

The beach became a claustrophobic trap. Those near the shoreline were caught between the rising, freezing waters of the English Channel and a solid wall of human pressure. There was no "out." St. John Ambulance crews were forced to abandon their posts because they were physically pinned against their own vehicles, unable to move through the density of the crowd to reach those fainting from dehydration or exhaustion.

For those at the very front, there was simply nowhere left to go but the water. As the shoreline vanished, dozens of ravers were forced into the dark, freezing English Channel. What could have been a mass drowning was mitigated only by the hundreds of small boats and vessels that had anchored offshore to watch the gig from the sea.

On the overhead promenade, the sheer weight of people was so great that there were genuine fears the Victorian structures would buckle and collapse onto the thousands dancing below. It was no longer just a concert; it was a test of survival where the only thing preventing a catastrophe was the collective calm of the audience.

The Human Toll

Against the odds, the mass catastrophe feared by the authorities never materialised, largely because of the "loved-up" nature of the dance crowd. Despite the density, the police made only six arrests. The violence and tribalism that often marred the era’s massive rock festivals were absent. As one security staff member succinctly put it: “If that had been an Oasis gig, we would have been fucked.”

However, the night was not without deep tragedies. A man in his 40s died on the beach after suffering a heart attack, and 26-year-old nurse Karen Manders lost her life due to head injuries following a fall from the railings onto the Lower Promenade. In the 'Right Here, Right Now' documentary, Cook reveals that Karen’s death has haunted him ever since. He reached out to her mother to offer his condolences, only to be told that her daughter had called earlier that night to say she was having the best night of her life.

Her mother thanked him for making Karen’s final night so special. “That really got to me,” he tells the camera tearfully in the documentary.

It was a tragic death in the circumstances. Manders would die in hospital a few days after the event, after sustaining serious head injuries following the fall.

160 people received minor injuries, and a further 11 were taken to the hospital. Only 6 arrests were made. Cook said, "At one point, I thought my nightmare scenario, that I might be responsible for someone being hurt or killed, was coming true. I was really rattled.

In 2023, The Guardian wrote: "The catastrophe the authorities had feared … never materialised ... The crushes, violence and drownings that could so easily have claimed scores of lives didn't happen." This was credited to the "loved-up dance crowd"

Aftermath: The Long Walk Home

The chaos continued long after the final track, 'Pure Shores', faded out.

Thousands headed to Brighton railway station for the 11:03 pm last train to London, but the power to the tracks had to be cut when people began falling from the platforms; some, in their desperation, even began walking along the tracks. With hotels full, thousands were left stranded, sleeping on a beach that now smelled strongly of urine and was covered in broken glass.

Emergency services were crippled. Some punters clung to ambulances to escape the crush, while other vehicles became hopelessly stranded in the mass of bodies. Paramedics were unable to reach audience members in need, and with the streets jammed, casualties had to be evacuated from the beach by lifeboats. A coastguard helicopter hovered over the shoreline throughout the evening, rescuing scores of unconscious people from the sea. The psychological toll was so high that half of the police officers who attended required trauma counselling.

The massive cleanup operation of the beach lasted several days and cost a staggering £300,000; Cook personally donated £75,000 toward the bill. More than 160 tonnes of rubbish were collected, and the promenade walls had to be sandblasted to clean them of the scent of human waste. According to The Guardian, Brighton "stank of urine for two weeks."

On the advice of his neighbour, Paul McCartney, Cook left the country for several days, fearing a massive public backlash. However, he was instead met with an outpouring of support from Brighton residents. The local newspaper, The Argus, printed a special supplement to publish letters of support, and BBC Southern Counties Radio was flooded with positive calls.

Reflecting on the event in 2016, Cook said: “I will always return to the mixture of elation and pure fear when we realised what we had created on that beach. The police were warning me exactly what might happen. And we were working all day to try and prevent that, whilst still entertaining and trying to put on a show. It was very edgy at times.”

'Big Beach Boutique II' remains the ultimate case study in event management, a beautiful, terrifying glitch in the matrix that united a generation of ravers in a way that modern health and safety would never permit. It was the day the "Superstar DJ" era peaked and then, by its own sheer weight, broke the system.

The gig fundamentally changed the landscape of British law. The subsequent 'Licensing Act of 2003' essentially signalled the end of the massive, unticketed free-for-all. Authorities realised that in a world of instant communication, "capacity" was a meaningless word without a perimeter fence and a barcode. Because of the "near-miss" on Brighton’s pebbles, the spontaneous mega-event was legislated out of existence.

So, not only can 'Big Beach Boutique II' never be allowed to happen again, it will never be allowed to happen again. It stands as a singular, sun-drenched monument to an era of irresponsible adventure, a moment in time when a quarter of a million people looked into the abyss, and instead of falling, they just kept dancing.

Thanks for reading

For Karen Manders

Jack