How the Hacienda Changed the World

From 1982 to 1997, The Haçienda was far more than a nightclub; it was a cultural landmark that helped reshape the landscape of music, nightlife, and youth identity in the UK. A hotbed of creativity and chaos, the club played a pivotal role in the emergence of new genres and cultural movements. Though its physical presence is no longer with us, its influence still resonates throughout Manchester and beyond.

If You Build It, They Will Come- Factory's Idea

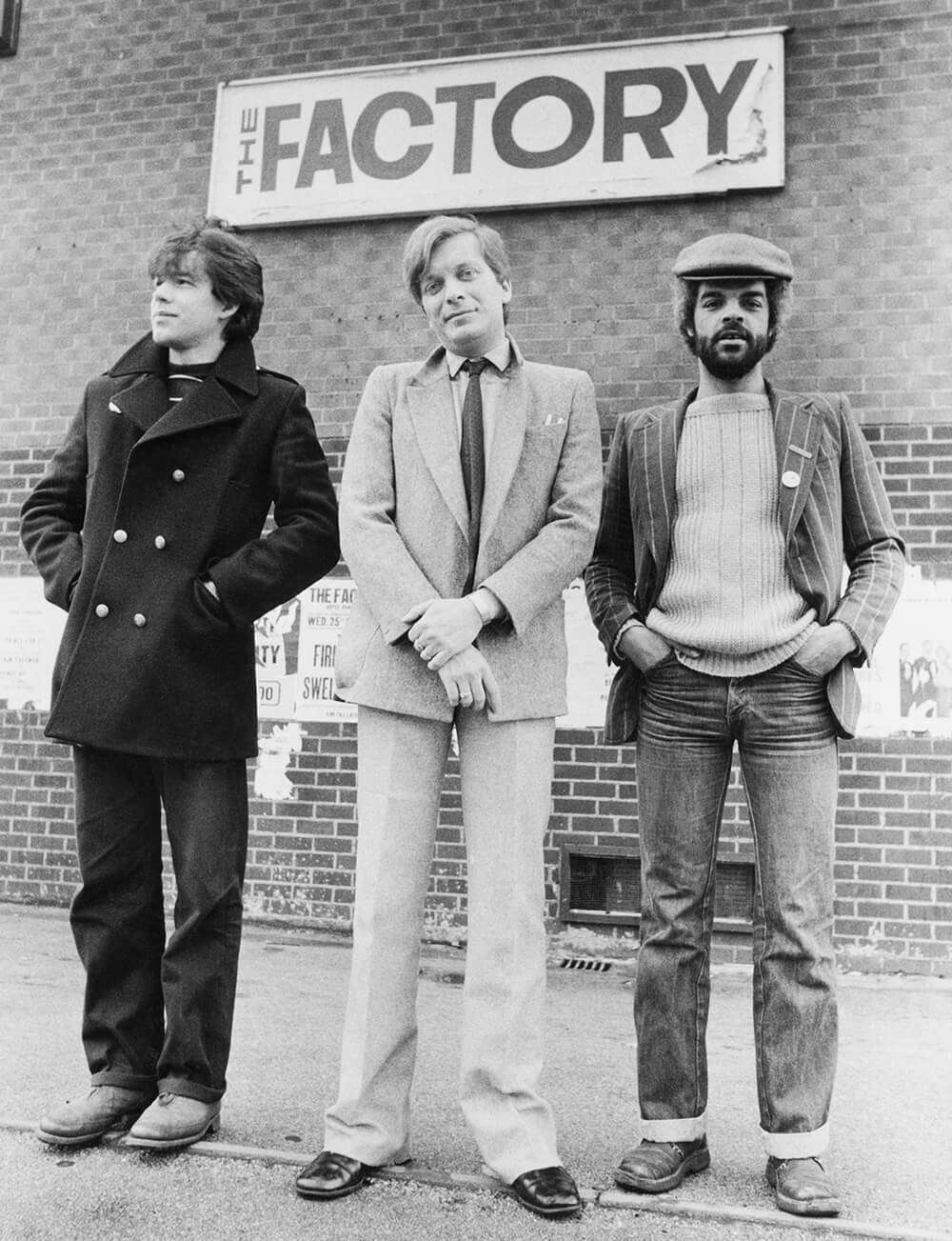

At the heart of The Haçienda’s story is Factory Records, the independent label that not only birthed the club but also revolutionised British music in the late 20th century. Founded in 1978 by Tony Wilson, along with musicians Alan Erasmus and Peter Saville, Factory Records was built on the idea of challenging the commercial music industry that dominated the charts. Wilson and his collaborators were determined to create music as art, not commerce. An ethos that would define both the label and The Haçienda, as well as much of Manchester’s cultural output for years to come.

From its very inception, Factory Records was driven by the belief that art and music should never be shaped by profit margins. Their approach was philosophical rather than commercial, encapsulated in the label’s famous motto: "You either make money, or you make history." This idea promoted a vision of music that broke free from corporate constraints, focused on artistic freedom, and nurtured musicians eager to push boundaries.

One of Factory Records’ most distinctive features was its refusal to sign formal contracts with artists. Instead, collaborations were built on mutual trust and creative freedom. A radical move in an industry defined by legal contracts and financial deals. Wilson famously described the label’s contracts as being "written on a handshake," a gesture that symbolised his belief in a more organic, collaborative approach to making music.

Factory’s first major success came with Joy Division, a post-punk band whose dark, emotive sound became a cornerstone of rock history. Formed in 1976 in Salford, the band, led by the enigmatic Ian Curtis, carved out a unique space in the music world with their atmospheric and often haunting style. Their debut album, 'Unknown Pleasures', with its sharp, introspective lyrics and innovative instrumentation, remains one of the most influential albums of its era. The band's sound combined elements of punk rock, electronic music, and atmospheric textures, creating a sound that was as emotionally intense as it was sonically groundbreaking.

Tragically, the band’s trajectory was cut short when Curtis died by suicide in May 1980, just before they were set to embark on their first U.S. tour. Despite his death, Joy Division's legacy only grew, with their music continuing to resonate across generations. The band's impact on both the post-punk movement and the broader music scene was immeasurable, influencing countless artists and genres. Their music became a touchstone for the darker, more introspective side of 1980s alternative music, and their influence can still be heard today in indie, alternative, and even electronic music.

After Curtis’s death, the remaining members of Joy Division: Bernard Sumner (guitar/keyboards), Peter Hook (bass), and Stephen Hague (drums) decided to continue making music together. They formed New Order in 1980, a band that would go on to define not just the Factory label but also the broader landscape of electronic music, dance culture, and the indie music scene. New Order’s sound marked a departure from the melancholic, post-punk style of Joy Division, incorporating electronic dance elements and synthesisers, creating a more upbeat and rhythmic sound. Their breakthrough single, 'Blue Monday', is often cited as the best-selling 12-inch single of all time, and its innovative blend of electronic music and post-punk elements set the stage for the rise of dance music in the 1980s and beyond.

New Order’s blend of melancholic lyrics and euphoric beats resonated deeply with club culture, and their influence on the development of electronic and dance music cannot be overstated. Albums like 'Power, Corruption & Lies' and 'Low-Life' pushed musical boundaries, combining synthesisers, drum machines, and guitars in ways that had never been done before. New Order's success allowed Factory Records to continue its experimental journey, and their music provided the soundtrack for the emerging rave scene in the UK and internationally.

With New Order’s commercial success, Factory was able to fund The Haçienda, a club that would become a cultural phenomenon in its own right, serving as the birthplace of the rave movement and a hub for Manchester’s evolving music scene. The investment by New Order, whose success had funded it, was a declaration of faith in The Haçienda’s cultural potential. It wasn’t just about having a nightclub; it was about creating an environment that would influence generations of musicians and music lovers. Even with its early financial losses, The Haçienda became a home for underground culture and a pivotal site for the UK’s rave scene, embodying the creativity and risk-taking that Factory Records was founded on.

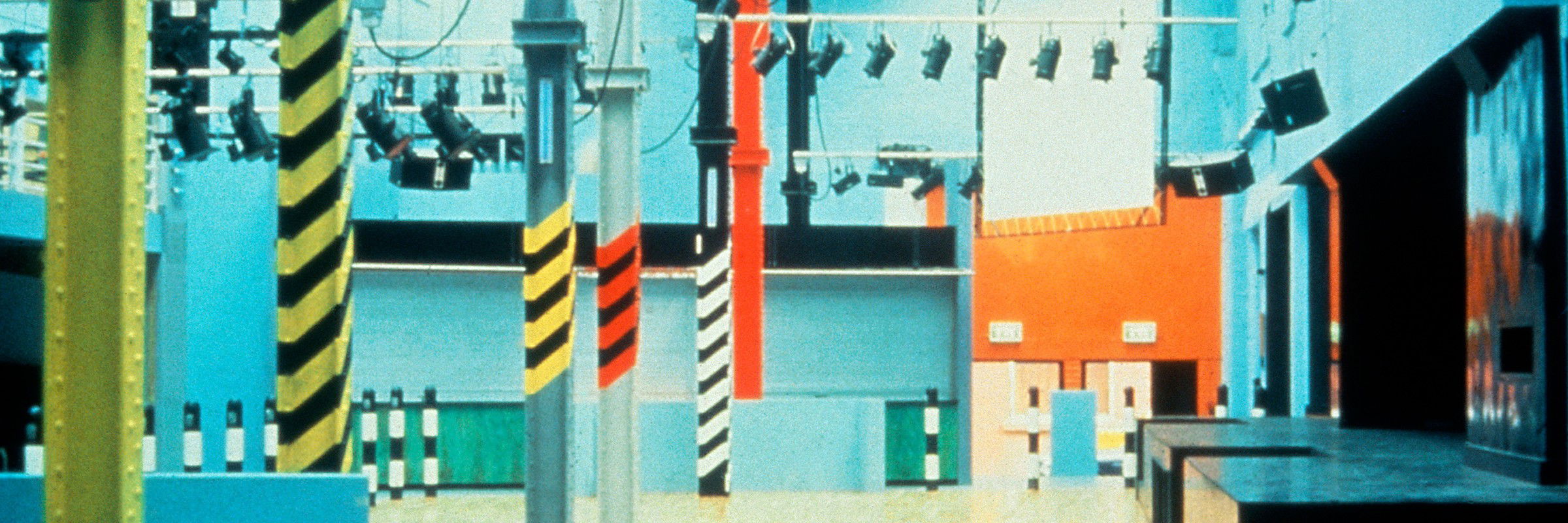

Ben Kelly, the architect behind The Haçienda’s design, played a crucial role in translating Factory’s anti-commercial ethos into the physical space. His design for the club was unconventional, reflecting the raw, industrial spirit of both Factory and Manchester itself. With exposed concrete, a minimalist layout, and bold use of lighting, Kelly’s design matched the no-frills, boundary-pushing attitude of the music played inside. The club’s design would go on to influence not just nightclub spaces but also broader trends in architecture, blending industrial chic with cutting-edge design. The Haçienda, with its stark aesthetics and visionary space, became an icon, both musically and architecturally.

On Stage- Manchester's Live Venue

The Haçienda wasn't just a nightclub; it was a launchpad for some of the most influential bands in British music history. While New Order, Primal Scream, and Happy Mondays are often highlighted, numerous other artists brought their unique sounds to the club's stage.

Despite their association with Rough Trade Records, The Smiths performed at The Haçienda during their early years. Their first show at the venue was on February 4, 1983, supporting funk band 52nd Street. They returned later that year, just after the release of 'This Charming Man,' marking their last appearance at the club.

Known for their psychedelic rock sound, Inspiral Carpets played at The Haçienda as they transitioned from indie cult favourites to mainstream success. Their energetic performances were a staple of the club's live music scene. Liam and Noel Gallagher made a memorable appearance at The Haçienda on September 5, 1994, to promote their debut album Definitely Maybe. Although they were more closely associated with The Boardwalk, their performance at The Haçienda remains a significant moment in the club's history.

In a surprising twist, Madonna performed at The Haçienda on January 27, 1984, as part of a live broadcast by the TV music show The Tube. She lip-synced to 'Holiday' and 'Burning Up,' marking a rare pop appearance at the venue. Before their rise to Britpop fame, Blur played at The Haçienda on November 12, 1990, to promote their debut single 'She's So High.' Their performance showcased the band's early sound and their connection to the Manchester music scene

Electronic pioneers Pet Shop Boys performed at The Haçienda on May 13, 1992. Their appearance was a nod to their collaboration with New Order's Bernard Sumner and The Smiths' Johnny Marr in the supergroup Electronic.

The Birth of Rave Culture- Acid House

By the late 1980s, The Haçienda had fully embraced the Acid House movement, whose roots lay in the underground club scenes of Chicago and Detroit. It wasn’t just a club. It was the beating heart of a youth revolution, and at the centre of this sonic uprising stood a trio of influential DJs: Mike Pickering, Graeme Park, and Dave Haslam.

Mike Pickering, who would later form M People, was one of the original Haçienda residents and a key figure at Factory Records. Was instrumental in introducing new, genre-defying sounds to Manchester. His sets mixed soul, funk, electro, and early house, laying the groundwork for what would soon become the UK’s Acid House explosion. When Graeme Park joined in 1988, the chemistry between them was electric. Park brought a deep knowledge of American house, an instinctive feel for the crowd, and a passion for pushing musical boundaries. Together, their back-to-back sets, particularly on the legendary Friday night 'Nude' eventsset a new benchmark for club culture in Britain.

Meanwhile, Dave Haslam brought a different but equally vital energy. A former music journalist turned DJ, Haslam became a resident in 1986 and played a pivotal role in diversifying The Haçienda’s sound. While Pickering and Park commanded the main Friday and Saturday night slots, Haslam held court midweek and at special events, curating eclectic nights that included everything from indie and alternative rock to hip hop and early electronic music. His nights, like 'Temperance Club' and 'Yellow', provided a vital counterbalance to the house scene, showcasing the wide cultural spectrum that The Haçienda embraced.

Haslam wasn’t just a DJ—he was a storyteller. He often spoke about the transformative nature of the dancefloor, recalling how it became a place where punks, goths, students, and soul boys all came together. In his memoirs, he describes playing 'This Is Acid' by Maurice or 'Strings of Life' by Derrick May and watching the crowd erupt, people hugging strangers, dancing with eyes closed, totally immersed. One night in particular, he recalled dropping 'Promised Land' by Joe Smooth at the peak of the night, and the reaction was so emotional, it felt "like a secular communion."

In 1988, the Second Summer of Love catapulted Acid House and rave culture into the mainstream. The Haçienda was at the centre of it all. As ecstasy (E) flooded the scene, the club’s atmosphere changed almost overnight. Alcohol was swapped for water; the aggression of earlier nights gave way to a sense of communal bliss. The dancefloor became a sanctuary. Pickering, Park, and Haslam each adapted their styles to suit the new mood, stretching out mixes, building tension, guiding dancers through waves of euphoria.

Tracks like 'Voodoo Ray' by A Guy Called Gerald and 'Pacific State' by 808 State, both closely tied to the Haçienda and Manchester’s underground, became national anthems. These records weren’t just played; they were broken at The Haçienda. The DJs were tastemakers, risk-takers, and cultural conduits.

The club’s success would help shape the DNA of British nightlife, inspiring the creation of future superclubs like Cream in Liverpool and Ministry of Sound in London. But The Haçienda was always more than just a venue. It was a movement powered by the passion of those who believed in music as a form of liberation.

Tony Wilson famously said The Haçienda was “a gift to the people of Manchester.” Through the hands and hearts of Mike Pickering, Graeme Park, and Dave Haslam, that gift became a transformative force. Together, they turned cold concrete and steel into a cathedral of sound and cultural change.

A Sanctuary of Inclusivity and Cultural Revolution

But The Haçienda’s role in the Acid House movement went beyond music; it was a space for transformation, a sanctuary for many. One of the most important communities it supported was the LGBTQ+ crowd. In the late '80s and early '90s, The Haçienda became one of Manchester’s most crucial LGBTQ+ venues, hosting the legendary Flesh nights, which became a cultural institution. Under the guidance of Mike Pickering, Flesh was a glamorous, inclusive event that welcomed people from all walks of life, giving a platform to queer culture in a time when such spaces were rare.

The Haçienda’s open-minded approach also allowed it to embrace a wide variety of subcultures, from indie rock and punk to new wave and ska. This openness not only shaped the club’s atmosphere but helped redefine the relationship between nightlife and identity, making The Haçienda a place where individuals could freely express themselves without fear of judgment.

By fostering inclusivity, creativity, and artistic freedom, The Haçienda became a cultural incubator. Its legacy remains an indelible part of Manchester’s evolution into a diverse, creative city. While the club may no longer exist, the spirit of The Haçienda, its contributions to music, culture, and identity, continues to echo through modern electronic music, rave culture, and the communities it helped empower.

Madchester

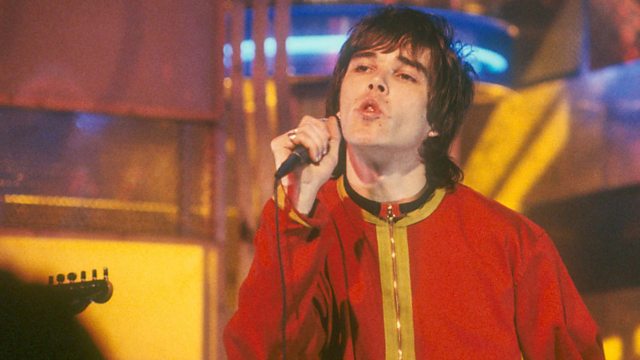

The Haçienda didn’t just birth Acid House in the UK. It was also the crucible for the Madchester movement, a psychedelic collision of indie rock and dance culture that redefined British music at the dawn of the 1990s. Led by The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays, Madchester fused jangly guitars, funk-drenched basslines, and house rhythms into something entirely new: a sound that was as hedonistic as it was hypnotic, rooted in the dancefloor but carried by the swagger of rock ‘n’ roll. And at the heart of it all was Factory Records, the label that not only ran The Haçienda, but also signed and nurtured the most chaotic and iconic band of the era, Happy Mondays.

Factory had already established itself as a radical force in independent music through Joy Division and New Order, but Happy Mondays represented a new chapter, raw, unpredictable, and completely plugged into the emerging rave culture. Their music, style, and attitude were inseparable from The Haçienda’s wildest nights. Tracks like 'Kinky Afro', 'Hallelujah', and 'Step On' were recorded with dancefloors in mind, blending live instrumentation with loops, samples, and grooves drawn straight from the club.

Fronted by Shaun Ryder, a poet of the streets with a knack for absurd, surreal lyricism, and backed by the permanently dancing Bez, the band blurred the line between performance and party. They weren’t just part of the scene; they were the scene. Their style, attitude, and sound embodied the messy, glorious spirit of Madchester. And thanks to Tony Wilson’s belief in their potential and willingness to fund their Chaos Factory Records, they were turned into unlikely pop stars.

The crossover moment came in November 1989, when both The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays appeared on the same episode of Top of the Pops. For those in the know, it felt like validation. For those watching at home, it was a revelation. The Stone Roses played a mesmerising version of 'Fool’s Gold', while Happy Mondays, joined by Kirsty MacColl, gave a loose, swaggering performance of 'Hallelujah' that seemed to throw out the rulebook of TV pop appearances.

That night, an underground scene rooted in Manchester’s clubs and record shops exploded into the national spotlight. The music wasn’t polished, the dancing wasn’t choreographed, but it was real—and people connected with it instantly. Suddenly, Madchester was everywhere: in the press, on the radio, in the charts. Top of the Pops had become the launchpad, and Happy Mondays, Factory’s unlikely house band, had helped kick the doors open.

Those performances on Top of the Pops in November 1989 didn’t just showcase a new sound; they shifted the entire trajectory of British music. The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays, beamed into living rooms across the country, brought the raw energy of Manchester’s underground to the mainstream. Suddenly, a youth movement that had lived in dark clubs and record shops was part of the national conversation.

At the centre of that cultural wave stood The Haçienda, more than just a nightclub; it was a Factory Records experiment in social architecture. Run by the same label that had signed Joy Division, New Order, and Happy Mondays, The Haçienda wasn’t just playing the music it was making it. And long after that Top of the Pops episode aired, the influence of that club, that scene, and that sound rippled outward, reaching a new generation of musicians who would go on to shape British music in the 1990s and beyond.

Among them was Noel Gallagher, who was deeply inspired by the Madchester era. As a young music fan living in Manchester, Noel was a frequent visitor to The Haçienda. In interviews, he’s recalled the experience vividly, not just the music, but the chaos and culture of the place. "Not only did I visit The Haçienda," he said, "but I got barred twice."

For Noel, the club wasn’t just a place to go out; it was formative. “I guess when the band formed, it felt like a rite of passage,” he later reflected. “We played there on the way up, like The Smiths. I saw Happy Mondays, New Order, and the great Primal Scream there.”

When Oasis burst onto the scene a few years later, they carried the spirit of Madchester with them, rebellious, euphoric, working-class, and completely unapologetic. Noel would go on to call the ages of 20 and 21 "the two best years" of his life, noting that The Haçienda was “the nearest place to my flat.” For him, as for many others, it was more than a club, it was a second home.

Meanwhile, New Order, perhaps Factory’s most successful act, were themselves reshaping their sound in real time under The Haçienda’s roof. Their 1989 album 'Technique' captured the very essence of the late-’80s cultural convergence. Recorded partly in Ibiza, it blended the band's post-punk roots with the growing influence of acid house, Balearic beats, and the Madchester groove pulsing through the club they helped finance.

Tracks like 'Fine Time' and 'Round & Round' were born of the same dancefloor ethos that drove The Haçienda’s late-night hedonism. The album’s seamless fusion of guitar-driven songwriting and electronic textures was a bold departure and a direct result of the cultural experiment Factory had set in motion. It was New Order’s most club-influenced album, and arguably the most emblematic of the label’s belief in tearing down boundaries between genres.

The Haçienda was at the centre of the musical universe in Britain. It had brought dance music to the masses, fused subcultures, and turned a gritty corner of Manchester into the heartbeat of a cultural revolution. Manchester bands ruled the world, the city’s swagger was unmatched, and The Haçienda stood proudly at the epicentre of it all. It was arguably Britain’s first superclub, not just a place to dance, but a symbol of creativity, possibility, and freedom.

All Good Things Come to an End

Despite being a groundbreaking musical and cultural hub, The Haçienda was notoriously mismanaged. From the very start, it operated at a loss, haemorrhaging money almost as quickly as it generated hype. The club’s ambitious design, conceived by renowned architect Ben Kelly, featured industrial minimalism and striking interiors that made a bold visual statement. But these innovations came at a high cost, draining the finances of both the venue and its owners.

Run by Factory Records, a label celebrated for its artistic integrity but infamous for its lack of business acumen, The Haçienda’s financial model was always precarious. There were no formal contracts, no proper budgets, and a philosophy that prioritised creative freedom over financial sustainability. With free or low-cost entry policies and a crowd fueled more by ecstasy than alcohol, the bar takings critical to the club’s revenue were dismal, even on packed nights.

By 1992, the dream collided with reality. The Haçienda filed for bankruptcy, burdened by spiralling operating costs and mounting debts. The costs of booking high-profile acts, maintaining the club’s expansive infrastructure, and keeping up with the ever-growing nightlife scene in Manchester drained resources rapidly. Worse still, illegal raves and warehouse parties began siphoning off the club’s core audience, offering similar experiences without the overhead of a formal venue.

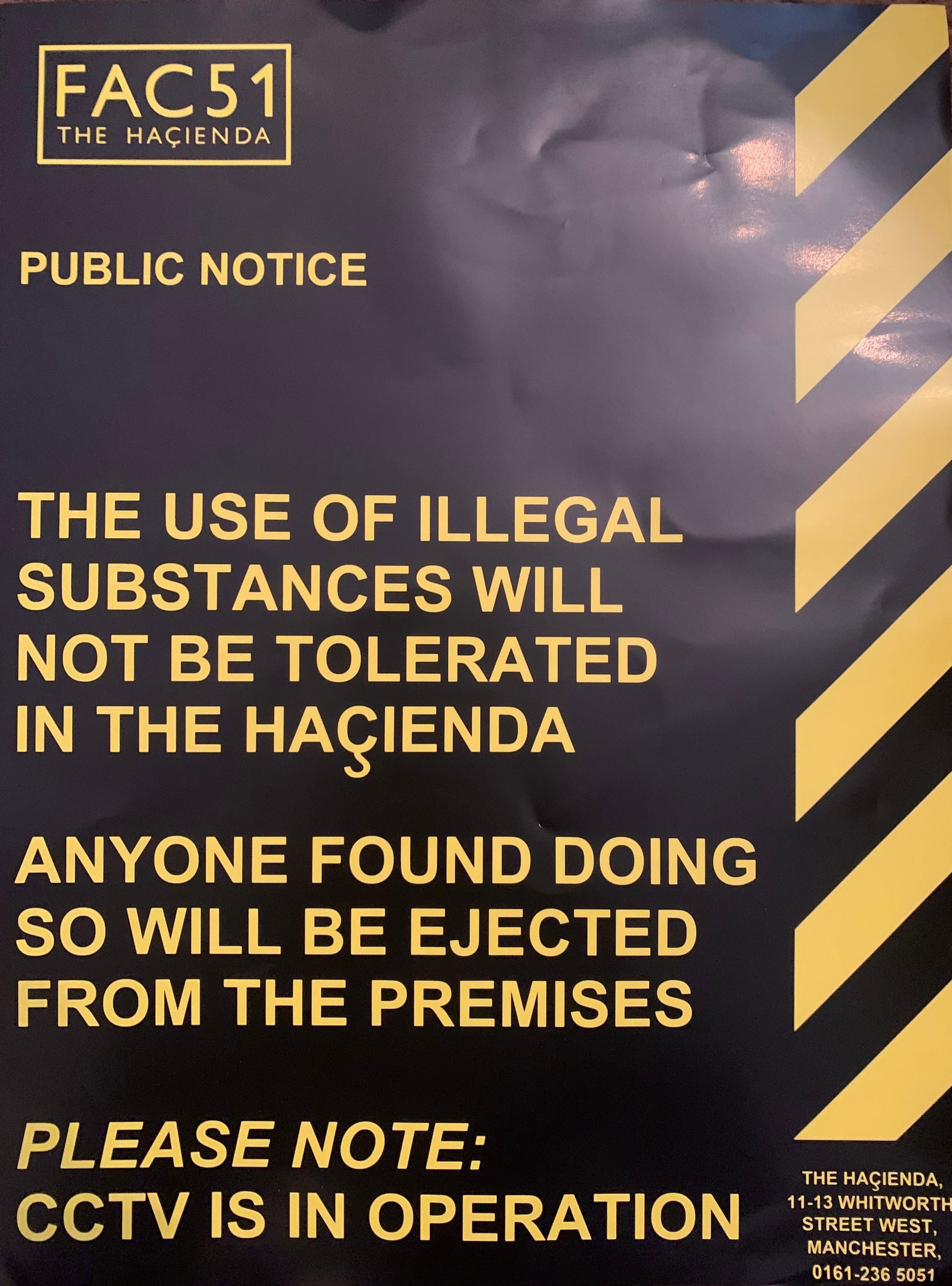

Meanwhile, the club’s open-door, inclusive ethos, a defining feature at its inception, became a double-edged sword. By the early 1990s, The Haçienda was increasingly plagued by gang activity, drug trafficking, and violent crime. What had once been a utopia of hedonism and freedom now felt increasingly dangerous. Stabbings, shootings, and intimidation became disturbingly frequent, pushing away regular patrons and deterring newcomers. Security struggled to keep control. Police presence grew. The dream of a safe, creative space was slipping away.

By now, The Haçienda had become a magnet for Manchester’s criminal underworld. The same openness that made it an experimental art space in the early ‘80s was now its biggest vulnerability. As ecstasy culture exploded and the club’s popularity soared, it attracted not only music lovers but drug dealers, gangs, and violent territorial disputes. The very atmosphere of freedom that had once defined it now left the club exposed.

The drug economy inside The Haçienda was impossible to ignore. MDMA (ecstasy) was pervasive, and while the club’s management was not openly complicit, it was largely powerless to stop its circulation. Security staff, often underpaid and undertrained, were ill-equipped to deal with the influx of illegal activity, and some were even reported to have ties to the very dealers they were meant to police. Attempts to crack down on drug dealing were often met with threats, intimidation, or worse. The club’s laissez-faire attitude toward regulation, once symbolic of artistic freedom, left it wide open for exploitation.

As the money flowing from drugs grew, so did the presence of rival gangs fighting for control of the lucrative market. Violence escalated quickly. Stabbings and shootings, both inside and outside the venue, became regular occurrences. By the mid-1990s, a night out at The Haçienda had begun to feel more like a risk than a release. Patrons were being searched at the door, police visits became routine, and many of the original crowd, the artists, students, and creative community that had built the Haçienda, started to stay away.

One of the most chilling moments came in 1997, shortly before the club’s closure, when a man was shot inside the venue. This brutal act was a devastating blow, a final confirmation that The Haçienda was no longer a sanctuary of music and freedom, but a battleground. It sent shockwaves through the city’s nightlife and made it clear to authorities, the community, and the club’s owners that the experiment had run its course.

As the pressure from the authorities mounted, the Greater Manchester Police began to apply consistent pressure, citing safety concerns and the strain on public resources. City officials, once proud of the cultural renaissance The Haçienda had sparked, now began to view it as a liability. Maintaining licenses became increasingly difficult, insurers started to back out, and public perception turned sour.

Even the club’s legendary status couldn’t save it. On June 28, 1997, The Haçienda closed its doors for good, not just due to debt or changing music trends, but because the very spirit of the venue had been overshadowed by something darker and more dangerous. It was no longer safe, sustainable, or aligned with the cultural vision it had once represented.

Legacy and Tributes

Though the original building was demolished and replaced with luxury apartments, The Haçienda remains an indelible part of Manchester’s identity and cultural legacy. It pioneered the very concept of the superclub, set the blueprint for nightlife as a form of cultural expression, and became the beating heart of the Acid House movement and the Madchester scene. Its fearless commitment to sound, community, and artistic risk continues to influence modern club culture, shaping iconic venues like Berghain in Berlin, Fabric in London, and countless underground raves and festivals worldwide.

More than just a venue, The Haçienda was a movement, a spirit, and a statement: that music could change a city, that community could be forged on the dancefloor, and that even the wildest dreams, despite their financial downfall, could echo through generations.

One of the most powerful tributes to The Haçienda came in 2002 with the release of 24 Hour Party People, directed by Michael Winterbottom and starring Steve Coogan as Tony Wilson. This wild, semi-fictional retelling of the rise and fall of Factory Records, Joy Division, New Order, and The Haçienda itself captured the chaotic brilliance of the era. With its fourth-wall-breaking narrative and documentary-style direction, the film embodied the spirit of the times. A mixture of genius and madness, idealism and dysfunction.

24 Hour Party People wasn’t just a biopic; it was a cultural artefact that cemented the mythology of Manchester’s music scene for a new generation. The film immortalised figures like Tony Wilson, Shaun Ryder, Ian Curtis, and the Happy Mondays, all of whom played pivotal roles in the club’s history. But more than that, it solidified The Haçienda not just as a club, but as a cultural revolution. For many who weren’t there to experience it firsthand, 24 Hour Party People became the gateway into the legend. It allowed younger generations to glimpse the raw energy and chaotic brilliance of the times, and in doing so, ensured that the story of The Haçienda would never be forgotten.

The Haçienda's legacy endures as one of the most significant cultural landmarks in the history of British music and Manchester’s evolution. It wasn’t just a nightclub; it was a movement that helped redefine music, youth culture, and the very essence of what it means to push creative boundaries. Despite its eventual decline and closure, the influence of The Haçienda continues to shape the sound of modern music and nightlife today. Its contribution to the rise of Acid House, the Madchester scene, and the birth of rave culture paved the way for countless musical subcultures and generations of artists. Beyond its musical impact, The Haçienda represented a spirit of inclusivity, experimentation, and rebelliousness that continues to inspire not just Manchester but the global music community. The club's story, one of innovation, excess, and unrelenting creativity, remains woven into the fabric of British music history, leaving an indelible mark that can never truly be erased, no matter how much time passes.