'Help': When the Battle of Britpop Took a Ceasefire for War Child

In the summer of 1995, the British music scene was defined by a single, loud narrative: the "Battle of Britpop." While Blur and Oasis were trading insults and fighting for the #1 spot, a much darker reality was unfolding 1,000 miles away. The Bosnian conflict was reaching a horrific crescendo, marked by the genocide at Srebrenica.

While the tabloids obsessed over chart positions, a group of music industry insiders—led by Tony Crean of Go! Discs and publicists Terri Hall, Anton Brookes, and Rob Partridge decided to pivot the industry’s competitive energy toward something vital. The result was 'Help', a charity album for War Child that remains the most authentic time capsule of 90s British music.

The Birth of War Child: From a Bakery to the Big Stage

Before it was a global phenomenon, War Child was the gut reaction of two British filmmakers, Bill Leeson and David Wilson. In 1993, while filming a documentary in the war-torn former Yugoslavia, they were horrified by the violence and ethnic cleansing they witnessed firsthand.

They didn't start with a record label; they started with a bakery. Shocked by the sight of snipers targeting children, they set up a mobile bakery in Camden and sent it to Mostar, Bosnia. It eventually fed 15,000 people a week, regardless of ethnicity.

The charity's connection to music began when a radio report about the bakery caught the attention of Anthea Norman-Taylor and her husband, Brian Eno. Eno brought in heavyweights like U2, David Bowie, and Luciano Pavarotti, laying the groundwork for 'Help'.

The "Instant Karma" Concept

The idea was born from a mix of urgency and flu-induced revelation. Tony Crean wanted to prove the industry could move faster than the bureaucracy of war. While bedridden in July 1995, watching the horrific news from Srebrenica, he was struck by the contrast between the glacial pace of political intervention and the speed of pop culture.

He drew inspiration from John Lennon, who in 1970 famously boasted that 'Instant Karma!' was recorded, pressed, and in the shops within a single week. Tony recalled Lennon’s philosophy that records should be like newspapers, immediate, reactionary, and raw. He didn't want a polished studio album; he wanted a "sonic dispatch" from the front lines of British music. The 'Help' team decided to mirror this breakneck schedule:

- Monday, Sept 4: Record the tracks.

- Tuesday, Sept 5: Master the album.

- Friday, Sept 8: In the shops.

To pull this off, they had to bypass the entire machinery of the modern music industry. There were no contracts, no long-term marketing plans, and no corporate red tape. They utilised a guerrilla approach: they simply called the studios and asked for the rooms for free, then called the bands and told them they had exactly 24 hours to deliver a master tape.

By the early hours of Monday morning, courier bikes were stationed across London and Europe, ready to act as the circulatory system for this massive experiment. If a band couldn't finish their track by the midnight deadline, they were out. This created a high-stakes pressure cooker environment that forced artists like Radiohead and Oasis to capture something lightning-fast and honest, the exact opposite of the over-produced, bloated sessions common in the mid-90s.

It wasn't originally going to be an album, though. The original plan was a concert: "The initial idea was a big gig with The Stone Roses and Black Grape", said Roses' PR Terri Hall. "But the venue, Old Trafford Cricket Ground, fell through." And in hindsight, we're so glad it did!

The Team Behind the Album

This logistical miracle was made possible by four key figures.

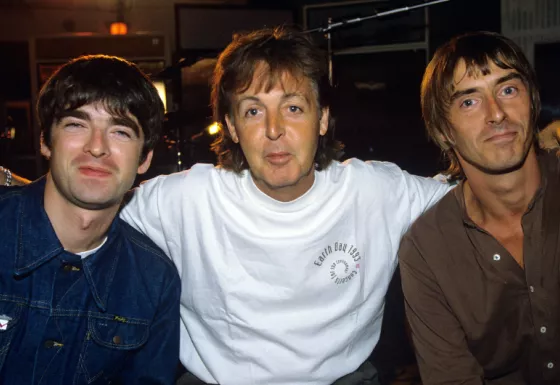

Tony Crean (The Visionary): As the International Marketing Manager at Go! Discs, Tony was the spark. His "Bed Revolution" was inspired by the Oasis lyric "I'm gonna start a revolution from my bed." Laid up with a fever, he realised that while he’d spent years obsessing over pop music, a genocide was happening under his nose. He became the bridge between Brian Eno’s high-concept humanitarianism and the raw grit of the Britpop scene. It was Tony who personally rang Paul Weller to suggest the "Macca" collaboration, essentially acting as the project’s creative director.

Rob Partridge (The Architect): A legendary PR man who had previously headed press at Island Records. Rob was the only person who didn't think the timeline was "nonsense." Having worked with Bob Marley and personally persuaded Island to sign U2, he had the most formidable contact book in London. He drew on his experience with the Toots and the Maytals live record, which used a similar lightning-fast turnaround, to coordinate over 20 studios and a fleet of courier bikes. Tony Crean famously called him a "magician" because he could solve any logistical nightmare with a single phone call.

Terri Hall (The PR Powerhouse): Head of the formidable Hall-or-Nothing PR. Terri was the "gatekeeper" to the era’s titans, representing Oasis, The Stone Roses, and Manic Street Preachers. Her personal trust with these bands was the project’s secret weapon. It was Terri who convinced the Manics to return to the studio for the first time since Richey Edwards vanished, and it was her relationship with John Squire that secured the album's iconic artwork. She treated her bands like family, and because she believed in the cause, they did too.

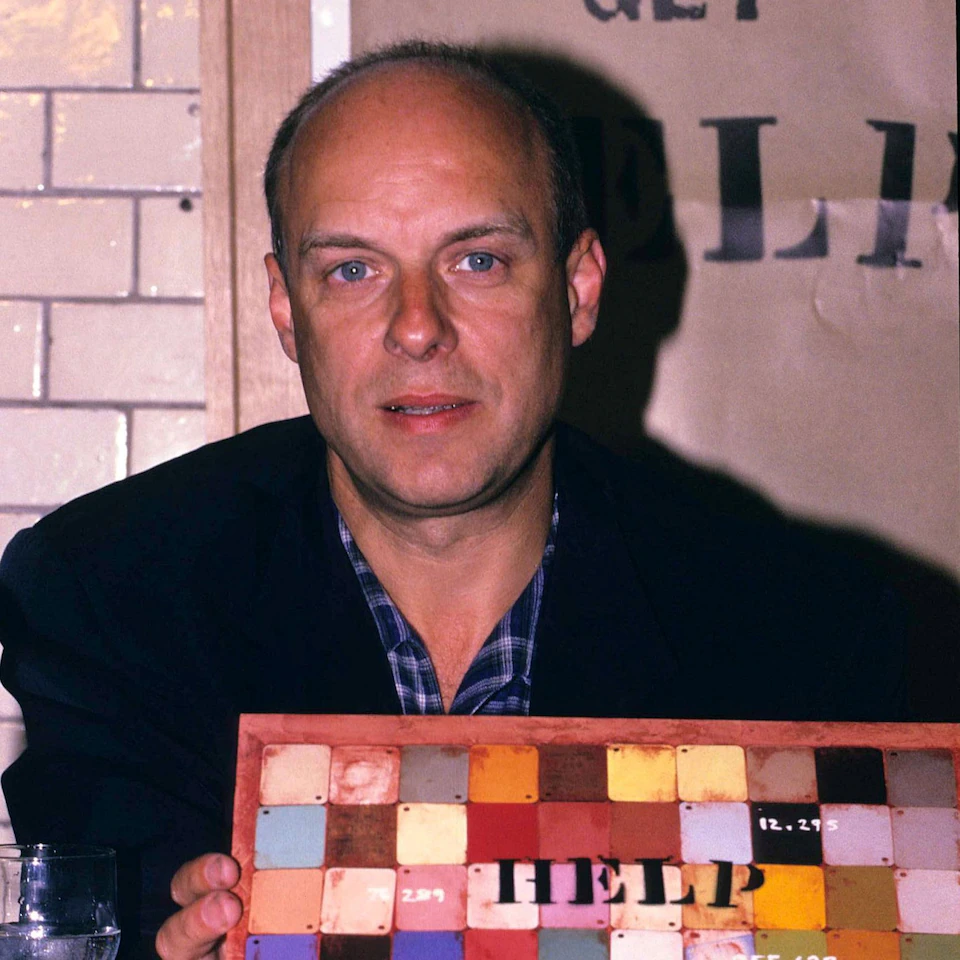

Andy Macdonald (The Maverick Mogul): The founder of Go! Discs, Andy was the definitive "Indie" boss who valued art over spreadsheets. When Tony pitched the idea, Andy didn't just approve it; he committed the entire label’s resources to it. He waived every penny of profit, provided the office space for the "war room," and blagged a private plane from the head of Polygram to fly the digital masters to a pressing plant in Holland. His willingness to take a massive financial risk ensured the record reached the shops by Friday morning.

Together, these four proved they could do what Lennon had dreamed: write, record, and release a record in a week. As Andy Macdonald later reflected, "Tony came into the office like a man possessed... we all just caught that energy."

The War Child Truce: Convincing the Titans

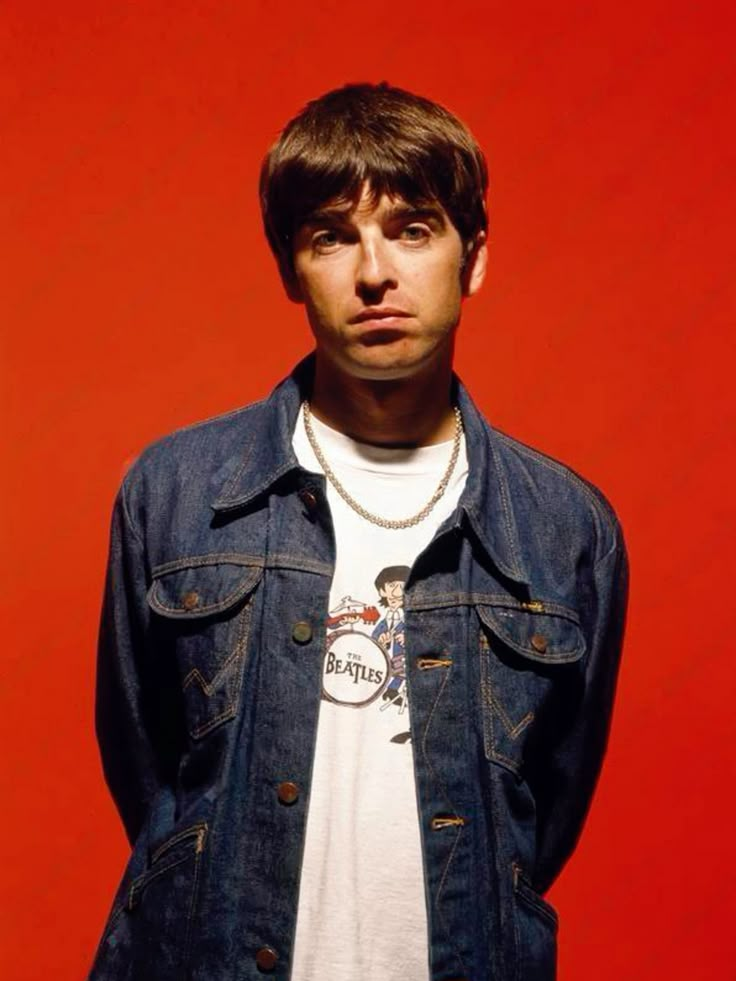

By August 1995, the Blur vs. Oasis rivalry was a media circus. Tony Crean used this as a lever. He framed the album as a "ceasefire"; if the two biggest bands in the country could stop fighting for one day, the world would have to notice Bosnia. Knowing both Damon Albarn and Noel Gallagher were Beatles disciples, he sold it as a tribute to Lennon’s legacy. Noel famously summarised the rare unity: "We’ll put aside our differences for the cause – and it’s the only time you’ll see the two of us agreeing on anything."

Noel Gallagher worked solidly for almost the entire 24 hours. He recorded two tracks, conducted interviews, attended photo sessions, and even personally hand-delivered Oasis' new version of 'Fade Away' to Radio 1.

Blur’s contribution was a testament to the band's creative fearlessness at the height of their fame. While the rest of the world expected a pop anthem, they delivered the experimental, mostly instrumental track 'Eine Kleine Lift Musik'. Recorded at Abbey Road, the title was a playful nod to Mozart’s 'Eine kleine Nachtmusik', but the sound was pure 90s art-pop.

Graham Coxon recalled the session as a chance to do something "a little bit jarring and strange," providing a perfect, atmospheric counterpoint to the more straightforward rock tracks on the record. By including them alongside Oasis, the 'Help' team successfully turned a toxic chart war into a unified front for humanitarian aid.

Iconic Sessions and Technical Hitches

The recording day was a high-stakes "pressure cooker." Tapes were being rushed to London from as far as Dublin and rural France. The Manic Street Preachers nearly missed the cut-off entirely when their tapes missed the last ferry from France. Neneh Cherry, recording in Spain, caught the last cargo plane out of Malaga by the skin of her teeth. Even Tony Crean crashed his car while trying to tune the radio during the frantic session window.

The Smokin’ Mojo Filters provided the album's most zeitgeist moment at Abbey Road Studio Two. While the headlines focused on the trio of Paul McCartney, Paul Weller, and Noel Gallagher, the session was a true gathering of mid-90s musical heavyweights.

The supergroup was rounded out by Steve Cradock and Damon Minchella of Ocean Colour Scene, who provided the driving guitar and bass, alongside the legendary Steve White on drums, a longtime collaborator of Weller’s from The Style Council. Adding a soulful layer to the track was Carleen Anderson, one of the most powerful voices of the Young Disciples and the acid jazz movement.

The atmosphere in the room was electric but daunting. Paul Weller was so nervous to work with "Macca" that he admitted to "self-medicating" to calm his nerves, and by the end of the day, he jokingly described himself as a "fucking mess." Meanwhile, Noel Gallagher arrived, was handed a guitar, and realised he didn’t actually know how to play the song.

McCartney, ever the professional, jumped in on the Wurlitzer piano and provided backing vocals, using his 1966 Epiphone Casino to add that unmistakable Beatles-esque grit to the recording. For the younger musicians in the room, watching a Beatle work in the very room where the original 'Come Together' was recorded felt less like a session and more like a religious experience.

Only six months after the release of 'The Bends', Radiohead gifted the project a brand-new track called 'Lucky'. Recorded in just five hours with Nigel Godrich, it would eventually become the emotional centrepiece of 'OK Computer'.

The song had been written by Thom Yorke during a tour of Japan and refined during soundchecks. Ed O’Brien recalled the recording session in a "shiny" central London pop studio, the kind used by ABBA and Take That.

O'Brien said, “If you take it out of the context of Help, it was also a really important track for us,” notes O’Brien, “because it was a transitional track from The Bends into OK Computer. And when we came to do the tracklisting for OK Computer, we were aware that a lot of people around the world hadn’t heard 'Lucky', because 'Help' was a UK-only release. It wasn’t even played on Radio 1."

For the Manic Street Preachers, the invitation to join 'Help' came at a time of profound trauma. The session marked the first time the band entered a studio since the disappearance of their lyricist and friend, Richey Edwards, on February 1st of that year.

"The existence of the band was very sketchy at that point," James Dean Bradfield reflected. "We were flailing." They were about to head to Normandy to record what would become 'Everything Must Go', and they used the 'Help' session as a vital test. They chose a breezy cover of 'Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head', a song Bradfield had been busking on tour. It was a poignant, fragile moment, a lighthearted pop melody carrying the unspoken, heavy weight of a band trying to find their footing in a world that had suddenly, violently changed.

The spirit of the album was bolstered by Suede, who delivered a masterstroke with their cover of the Elvis Costello and Clive Langer classic 'Shipbuilding'. Chosen for its haunting relevance to conflict-torn towns, Brett Anderson’s melancholic, piano-led vocal performance cut through the noise of the era with sombre beauty.

Portishead contributed 'Mourning Air', a track so haunting it perfectly matched the sombre reality of the Bosnian conflict. The Chemical Brothers (then at the absolute vanguard of the "Big Beat" movement) turned in 'Loop-Up-Free-Way', proving the electronic scene was just as engaged as the guitar bands.

Then there was the legendary arrival of Sinéad O’Connor’s contribution. Her sparse, percussion-heavy version of 'Ode to Billie Joe', complete with the haunting sample of a crying baby, actually arrived via courier after the mastering deadline had technically passed. The performance was so powerful that the producers felt they had no choice but to reopen the album to include it.

Over in Sweden, Neneh Cherry was recording at the legendary ABBA studios in Stockholm. Using the original ABBA keyboards, she turned an old nursery rhyme into '1, 2, 3, 4, 5'. Her motivation was simple and direct: "War is bad. Children do not fare well in a war."

The album also featured a charming, loungy collaboration between Salad and the late, great Terry Hall. Their version of 'Dream a Little Dream of Me' became one of the record's most beloved tracks, later leading to a memorable performance at the Mercury Music Prize ceremony. It perfectly encapsulated the "eclectic" nature of 'Help', where the indie-pop quirk of Marijne van der Vlugt could sit comfortably alongside the deadpan cool of a Specials legend.

Perhaps the most extreme contribution came from One World Orchestra (The KLF). True to their reputation as industry disruptors, Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty finished their track 'The Magnificent' at 10:00 AM, talked the Yugoslavian embassy into issuing them visas by 10:30 AM, and promptly boarded a plane to Sarajevo. Their goal was to debut the track on the underground B92 radio station in the very city the album was intended to help, all while the war was still actively raging around them.

The track itself was a rework of the theme from 'The Magnificent Seven', but it almost featured the most famous runaway in pop history. Robbie Williams, who had just sensationally quit Take That.

Tony Crean said, "The only person who didn’t make it was Robbie Williams. Robbie had left Take That, and he’d been around all summer. You’d go to a gig or aftershow and bump into him. I sent Bill Drummond [The KLF] a fax and said, “I know you’re not doing anything, but how about doing a track with Robbie?” Then, after being around every bloody week, Robbie went on holiday with his mum. In the end, they had to do it without him [as the One World Orchestra]."

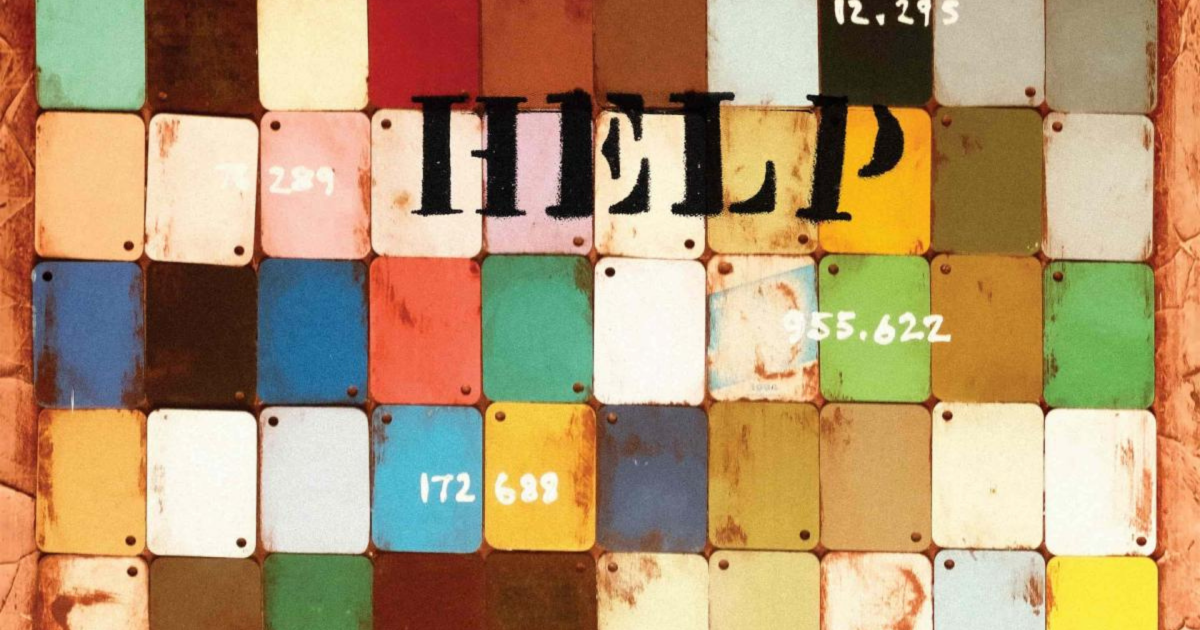

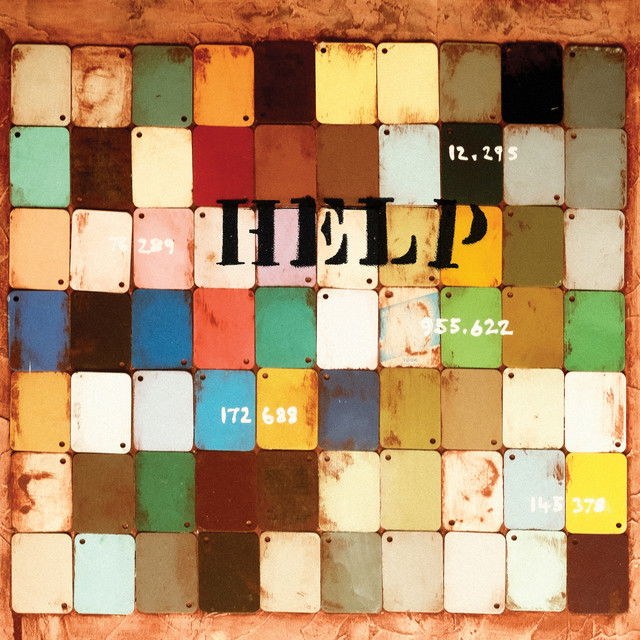

The Artwork and The Stone Roses

The aesthetic of the album was a masterstroke of indie credibility. John Squire of The Stone Roses provided the cover art in his signature action painting style, ensuring 'Help' looked like a high-end piece of art rather than a standard charity compilation. Squire, who had famously designed the iconic Pollock-influenced artwork for 'The Stone Roses' debut album, brought that same prestigious, painterly energy to this project.

His visual identity helped the LP stand out on the shelves of HMV and Tower Records just five days after its conception. By having the era's most celebrated visual stylist create the sleeve, the organisers ensured the record felt like an essential artefact of the 90s, rather than just another charity release.

The design of the artwork happened so fast that there was no time to include a track listing.

The band also contributed a unique version of 'Love Spreads', which remains a significant piece of band trivia. Unlike the polished, heavy blues of the version found on their album 'Second Coming', the 'Help' version is raw, crispier, and features a prominent piano solo. Crucially, it is the only studio recording in the band’s history to feature the post-Reni lineup, with Robbie Maddix on drums and Nigel Ippinson on keyboards. For fans, this unpolished, one-day session captured a rare and fleeting version of the group that never appeared on a studio album again.

This session was particularly symbolic because The Stone Roses were notorious for their glacial pace in the studio, famously taking five years to complete their second album. To have them agree to, and successfully deliver, a track within the 24-hour 'Help' deadline was nothing short of a miracle. It showed the immense respect the band had for Terri Hall and Tony Crean, and proved that when the cause was urgent enough, even the most meticulous artists could embrace the "Instant Karma" spirit.

Chaos, Technical Hitches, and the Chart Battle

The project was plagued by a series of high-stakes "technical hitches" that threatened to derail the entire mission. Tony Crean, the album's mastermind, was so consumed by the logistics that he actually crashed his car while frantically trying to tune the radio to catch session updates. Meanwhile, across the channel, the Manic Street Preachers’ tapes missed the last ferry from France, and Neneh Cherry’s contribution only made it onto the final cargo plane out of Malaga by the skin of its teeth.

Despite these near-disasters, the final production phase was a feat of sheer endurance. The legendary Brian Eno, who had been the creative catalyst for the project from the start, took the reins to mix and master the entire record. Operating out of Townhouse Studios, Eno went into overdrive to ensure the 20 disparate tapes arriving from across the UK and Europe were polished into a cohesive masterpiece.

The mastering was finalised by 9:00 PM on Tuesday, but the race was far from over. From there, it was a literal sprint against the clock; as bad weather grounded planned helicopters, the tapes were rushed to pressing plants in Blackburn, Telford, and Holland via a fleet of courier bikes, some allegedly granted police escorts, and a private jet that made a whirlwind trip across Europe to drop off the digital masters.

Upon release, the NME gave it a 10/10 review. It sold over 70,000 copies on day one and would have reached Number One, but the Official Charts Company ruled it a "compilation." War Child tried to declare all artists were part of a supergroup called War Child to bypass the rule, but the authorities refused.

The Awards Sweep: From the Mercury to the Brits

The impact of 'Help' was so profound that it reached the corridors of power. At the Q Awards in November 1995, Tony Blair, then the Leader of the Opposition and just months away from his landslide victory, presented a special award to War Child. His speech acknowledged that the music industry had succeeded where diplomacy had stalled:

"At a time when there was a danger of the West turning its back on the war in Bosnia, [the album] helped put it back in the headlines and reactivate public interest. It helped us be aware of our responsibilities to other people."

The industry continued to shower the project with accolades well into 1996. In an unprecedented move, 'Help' was nominated for the Mercury Music Prize. While Pulp eventually took the trophy for 'Different Class', Jarvis Cocker used his time on stage to pay tribute to the War Child project; the band also donated their prize money to the charity.

The following February, 'Help' was honoured again at the BRIT Awards, the same infamous night that Jarvis Cocker stage-invaded Michael Jackson. Amidst the chaos and the "excess" of the evening, Thom Yorke provided the emotional heart of the ceremony. Accepting a special British Music Industry Award on behalf of the project, he reminded the glitzy audience of the album's urgent origins:

"For one day last year, we all stopped fighting and actually did something decent for once."

A Legacy in Pounds and Lives

'Help' went on to raise £1.25 million, over six times the amount the organisers had initially hoped for. These funds didn't just disappear into administrative black holes; they built the Pavarotti Music Centre and funded convoys that kept children alive through the Bosnian winter.

In the words of Rob Williams, CEO of War Child UK:

"The 'Help' album enabled War Child UK to bring security and education to thousands of children in 1995, and created an enduring bond between the UK music industry and the fate of children caught up in wars."

The Final Cut: A Time Capsule of Excellence

While the mid-1990s are often remembered for debauchery and chart wars, 'Help' captures the era’s true creative peak, the moment alternative music became the mainstream voice of a generation's conscience.

It remains a staggeringly diverse and eclectic record. It brought together the guitar-heavy grit of Oasis and The Stone Roses, the atmospheric trip-hop of Portishead, the dance energy of The Chemical Brothers, and the haunting vocals of Sinéad O’Connor and Suede. It even managed the impossible: reuniting a generation of artists with a Beatle to create something raw, immediate, and lasting. It remains, quite literally, the best record a single day ever produced.

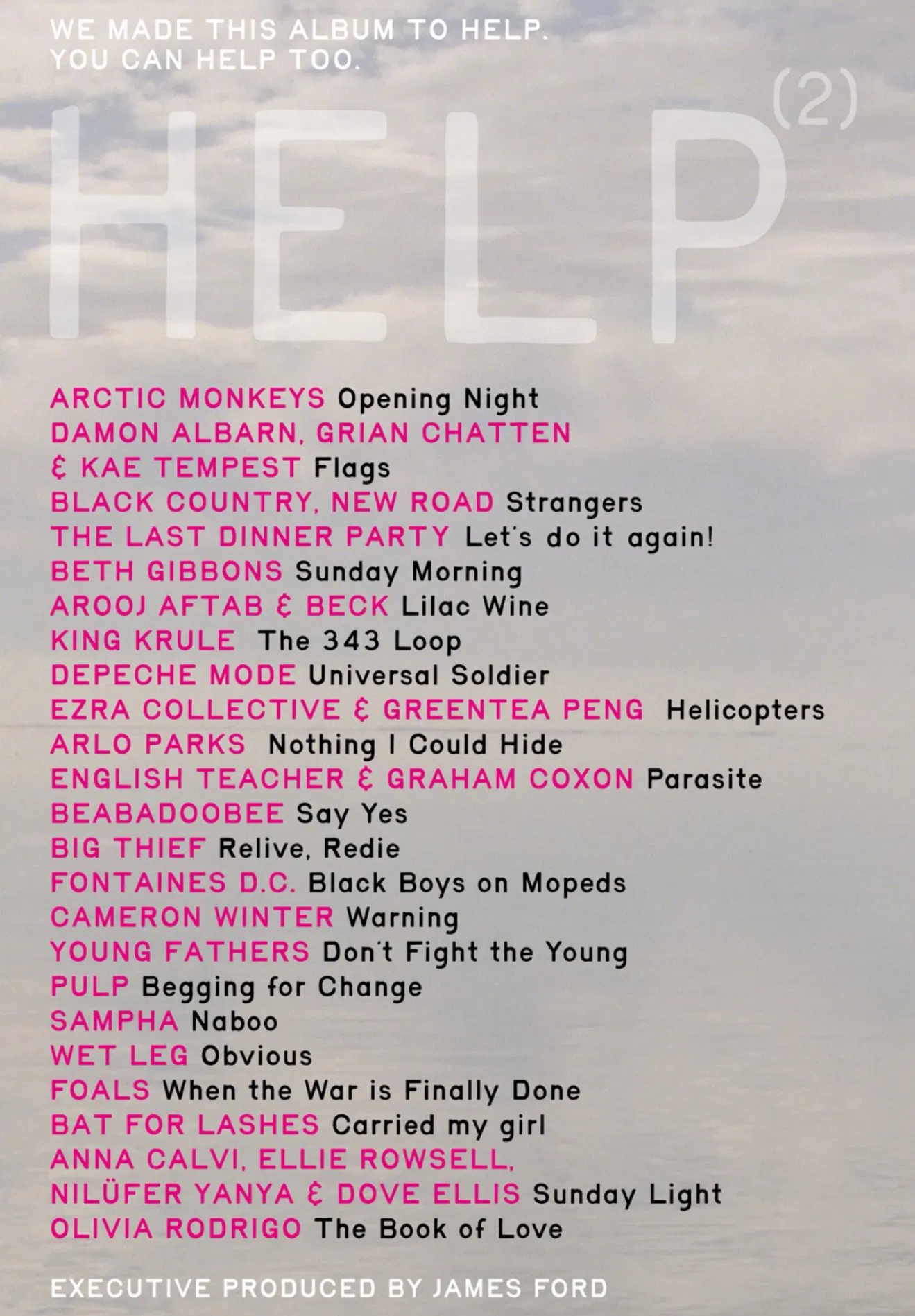

The Legacy Reborn: 'Help (2)'

Thirty-one years after the original "miracle," the mission has come full circle. Arriving on March 6th, 2026, 'Help (2)' serves as the ambitious successor to the 1995 landmark. While the original was recorded in a 24-hour sprint, this new volume was captured during an intensive week at Abbey Road Studios in November 2025. The urgency, however, remains just as dire; with 1 in 5 children worldwide now living in conflict zones, the industry has once again mobilised to turn compassion into action.

A Production Miracle: James Ford’s Hospital Bed "War Room"

The project was stewarded by producer James Ford, who faced a staggering personal crisis just as the sessions began: a diagnosis of leukaemia. In a modern echo of Tony Crean’s 1995 flu-induced epiphany, Ford produced the record from his hospital bed. "I was in the ICU with a pipe coming out of my neck," Ford revealed. "But because of technology, I could be on my laptop, listening to what they were doing on the desk." From his bed, Ford guided Olivia Rodrigo through vocal takes for 'The Book of Love' while receiving a blood transfusion, a bizarre but life-saving focus that kept the project on its "Instant Karma" trajectory.

Icons, Newcomers, and the 'Flags' Collaboration

The record bridges the gap between the legends of the original 'Help' and the modern vanguard. The experimental heart of the album is 'Flags', a single released today (February 12th) featuring a powerhouse alliance of Damon Albarn, Johnny Marr, Kae Tempest, and Grian Chatten of Fontaines D.C.

The session for 'Flags' was described by Tempest as a "baptism of fire" and a "fever dream." The recording featured:

- Guitars: Johnny Marr and Adrian Utley (Portishead).

- Rhythm Section: Femi Koleoso (Ezra Collective) and Seye Adelekan (Gorillaz).

- The Choirs: A 43-piece children's choir joined by an "all-star" ensemble including Jarvis Cocker, Carl Barât, and Declan McKenna.

The Centrepiece: Arctic Monkeys 'Opening Night'

Anchoring the 'Help (2)' project is the lead single, 'Opening Night', the first new material from Arctic Monkeys in four years. By stepping out of their hiatus to lead such an urgent collection, the band set a sophisticated, somewhat surreal tone for a record that refuses to look away from the global crisis.

Sonically, 'Opening Night' is a fascinating synthesis of the band’s entire history. It eschews the polished, leather-jacket swagger of 'AM' for something far more intimate and unsettling. The track opens with wiry, robotic percussion and clean, fingerpicked guitar lines that feel low-key and vulnerable.

As the song unfolds across its four-minute runtime, it begins to harken back to the lush, cinematic orchestration of 'The Car', with sweeping strings that add a sense of grand drama. Yet, beneath that elegance lies a grit we haven't seen in years—flashes of murky, sinister guitar work that feel pulled straight from the 'Humbug' era, providing a dark counterpoint to the orchestral swells.

Lyrically, Alex Turner dials up the stage lights on self-mythology and the weight of first impressions. The song is packed with surreal imagery, "popular slogans in a bucket of pain" and "mystery boxes from which you cannot escape." The centrepiece is the chorus, where Turner utilises a gambling motif to describe a world that feels fundamentally unfair:

"Tonight is heavy on one side, sort of like / A set of cherry red and white loaded dice"

Interestingly, the song has roots that stretch back as far as the original 'Help' legacy. Turner revealed that 'Opening Night' was based on an unfinished demo he first composed ten years ago. Returning to it at Abbey Road in November 2025 felt like a "transitional" moment for the band. As drummer Matt Helders noted, the focus was never on seeking attention for their return, but on the cause.

A Handshake Across Decades

The tracklist is a map of modern music’s most vital voices. Arctic Monkeys broke a four-year hiatus to lead the project with 'Opening Night', a track that synthesises the cinematic strings of 'The Car' with the murky grit of 'Humbug'. In other rooms of Abbey Road, the band English Teacher recorded 'Parasite' with Graham Coxon on guitar, a "nervous hush" falling over the room when the Blur legend walked in.

The record also features poignant nods to the past. Fontaines D.C. recorded a haunting cover of Sinéad O’Connor’s 'Black Boys On Mopeds', while Depeche Mode turned in an electronic reimagining of 'Universal Soldier'.

Other highlights include:

- Olivia Rodrigo & Graham Coxon: 'The Book of Love'.

- Pulp: 'Begging for Change'.

- Foals: 'When The War is Finally Done'

New material from: Beck, Sampha, Arlo Parks, Wet Leg, and The Last Dinner Party.

Through the Eyes of a Child

In a moving creative choice, the sessions were filmed by eight nine-year-olds using Handycams under the supervision of Oscar-winning director Jonathan Glazer. The "organised chaos" saw children pushing aside Johnny Marr’s guitar neck to get the perfect shot, while Jarvis Cocker encouraged the choir to "make a noise" rather than sing traditional songs. This footage was spliced with film from children on the front lines in Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan, creating an unbreakable link between the studio and the reality on the ground.

Against the Odds: How Flu, Feuds, Hospital Wards and a Beatle Built the ‘Help’ Legacy

Ultimately, the two ‘Help’ records serve as twin pillars of a musical conscience, spanning thirty years of conflict and creativity. Despite the shadow of staggering obstacles, from Tony Crean’s flu-induced revelations in 1995 to James Ford’s heroic production from a leukaemia ward in 2025, the music industry has twice achieved the impossible. These albums were forged in the heat of near-misses, logistical chaos, and the raw grief of bandmates passing, yet they delivered collections of brilliant, enduring songs that transcend the typical charity compilation.

Whether it was the legendary "sonic ceasefire" that saw two warring factions in Oasis and Blur agree on a single cause, or the monumental return of Arctic Monkeys from a four-year silence, the spirit of the project has remained remarkably consistent. By bringing together the "Instant Karma" energy of The Beatles' legacy with the modern vanguard of 2026, these sessions proved that music is at its most potent when the stakes are highest.

Through the feuds, the fever, and the decades, one truth remains: the notes on the tape are the only things that can truly cross borders. I’ll leave you with the words of Richard Ashcroft: 'Music is power